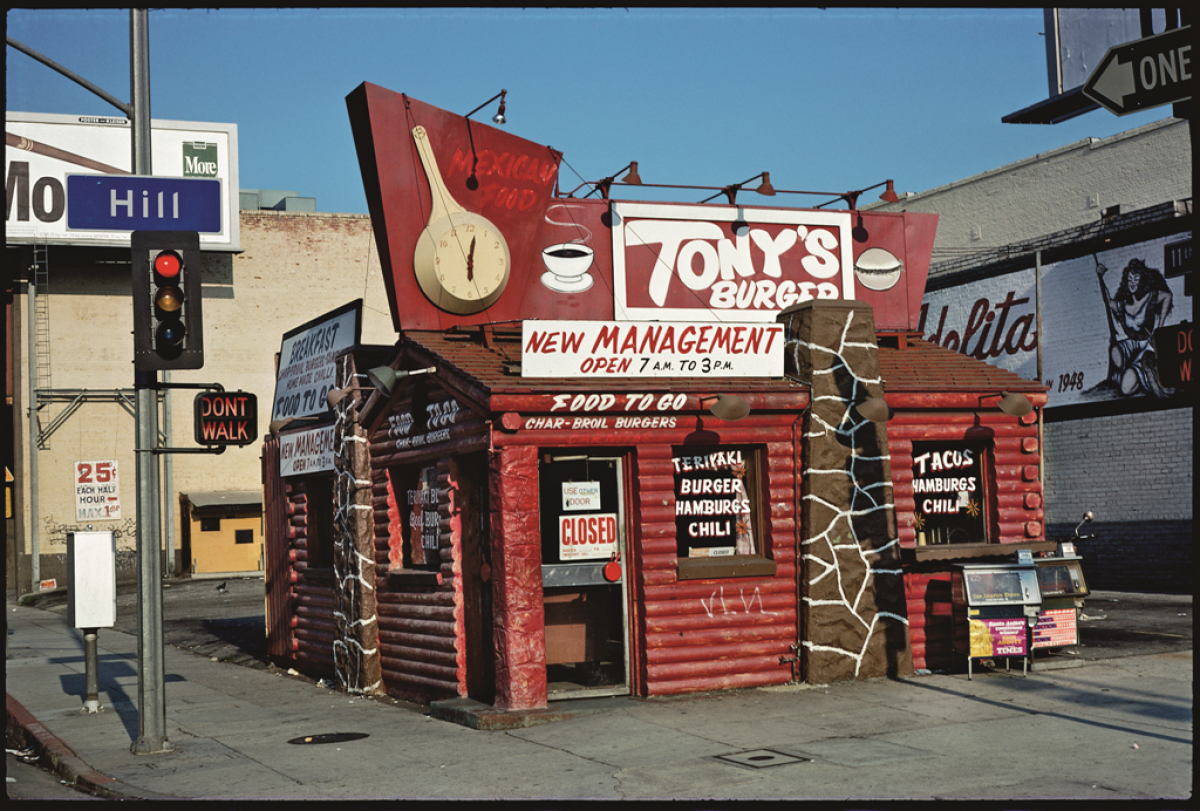

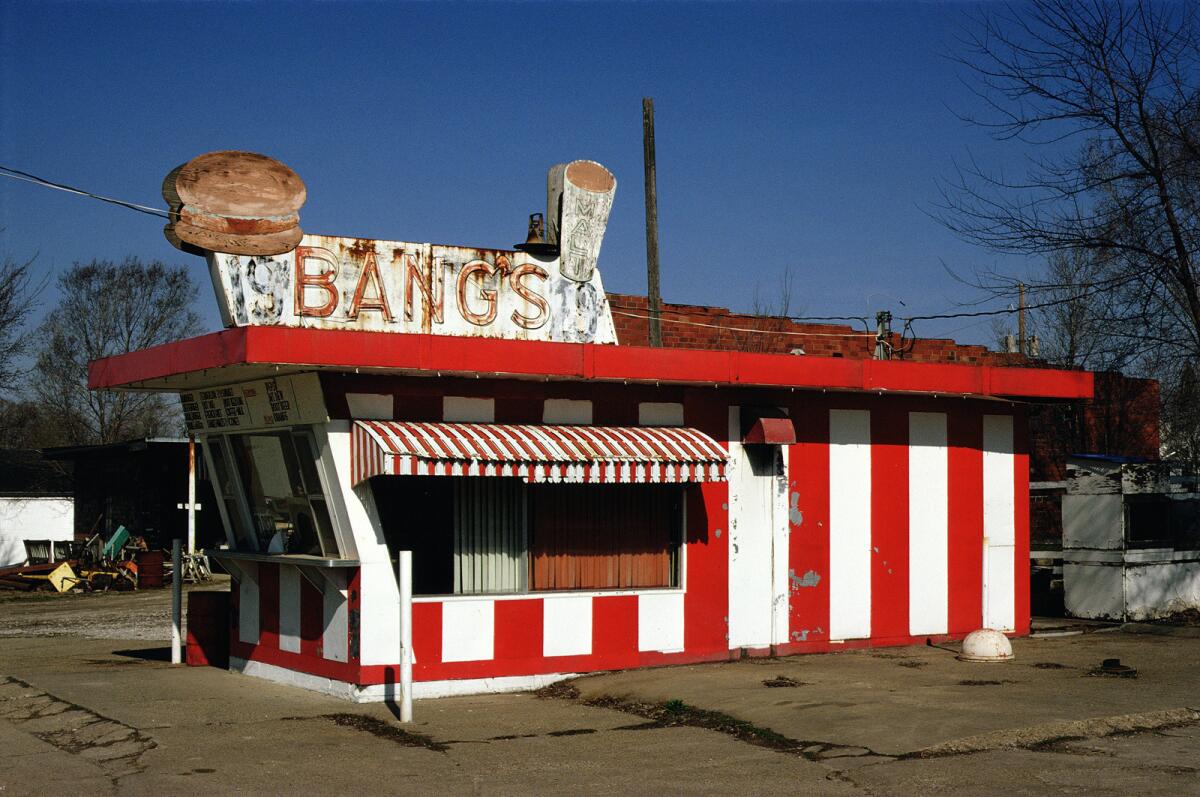

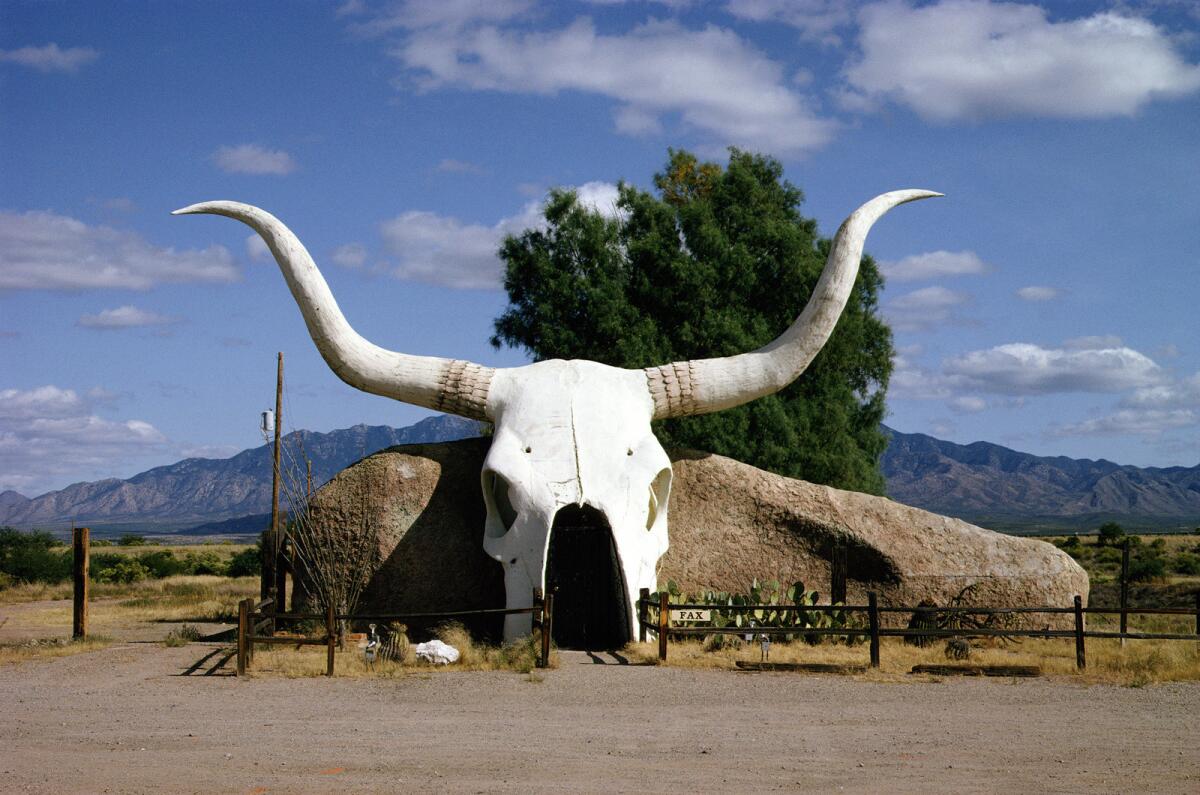

Farewell to John Margolies, who glorified the diners and motels of roadside America and left us 13,000 photos

Travelers, let us now raise a glass--or perhaps a curvy old Coca-Cola bottle, freshly pried from a vintage service station fridge--to John Margolies, author, photographer, lecturer, road-trip royalty.

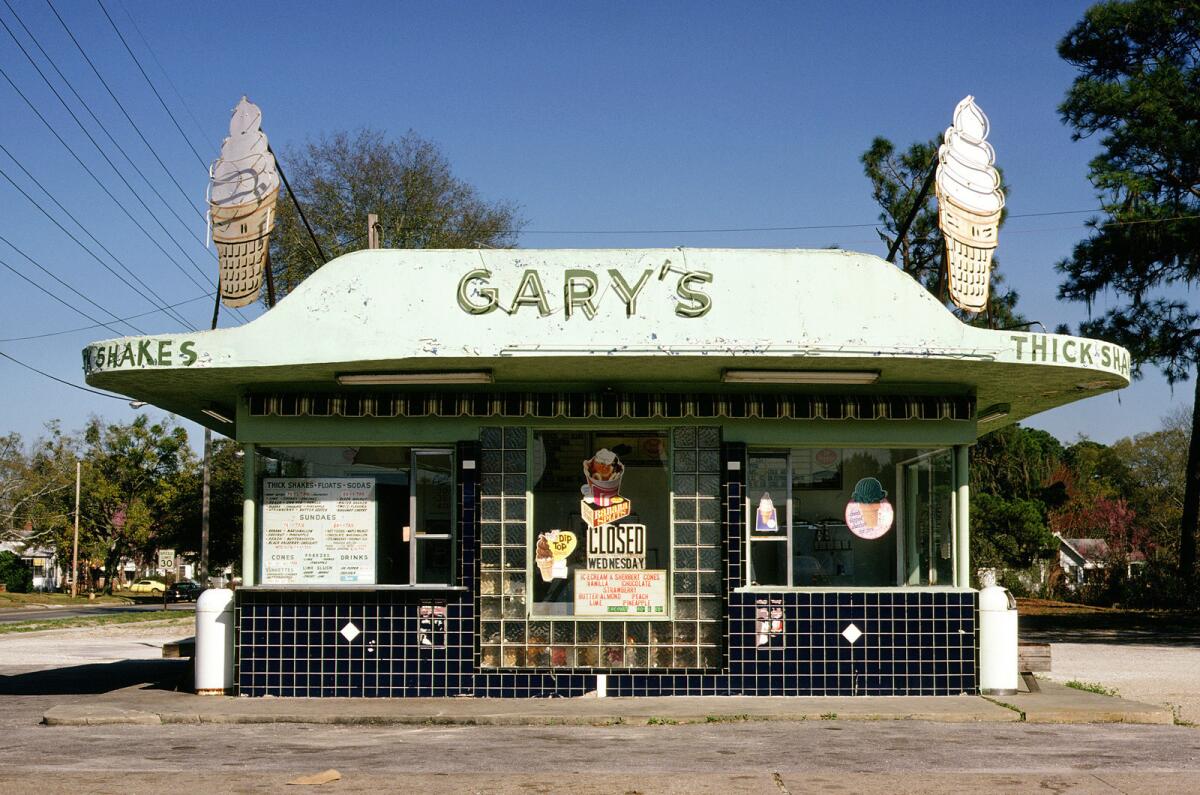

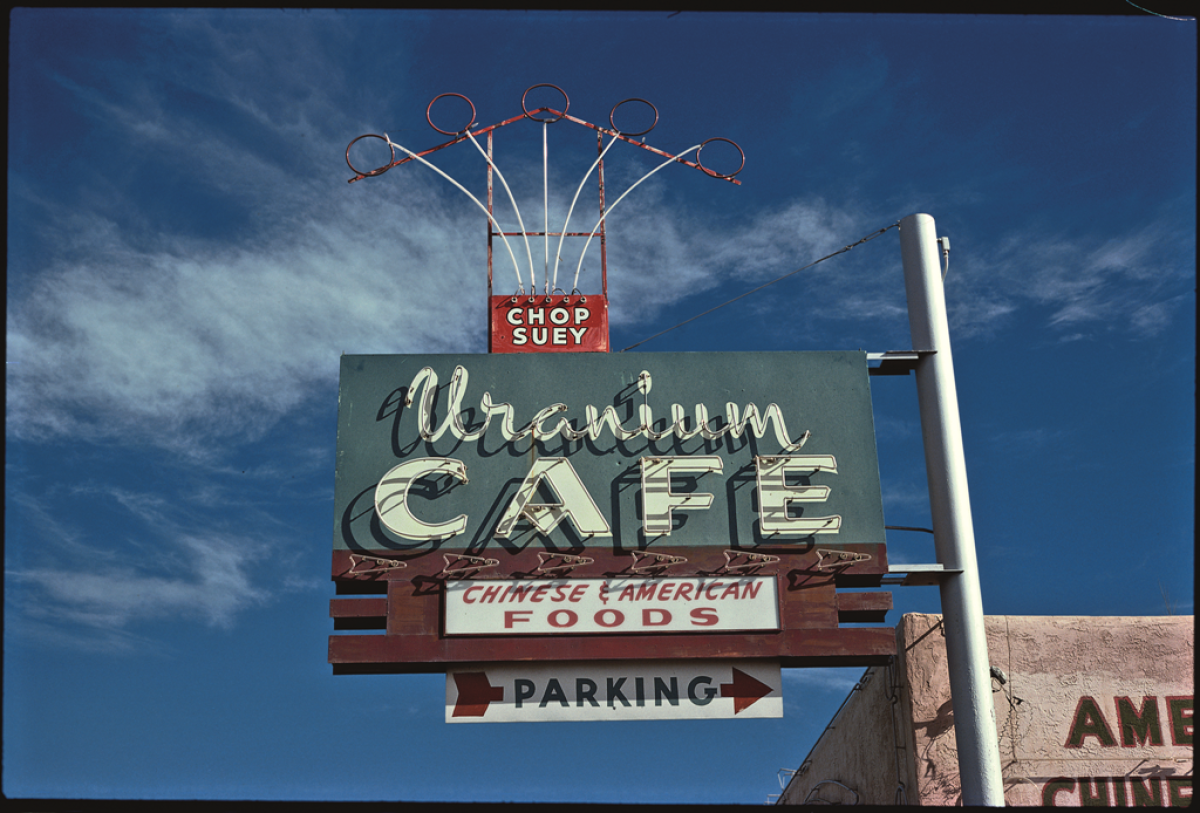

Before Margolies came along, there was a little less love in this country for drive-through doughnuts and neon sombreros. But Margolies, 76, who died of pneumonia on May 26 in New York, spent most of his adult life seeking, snapping and celebrating the commercial imagery of America’s Main Streets and blue highways.

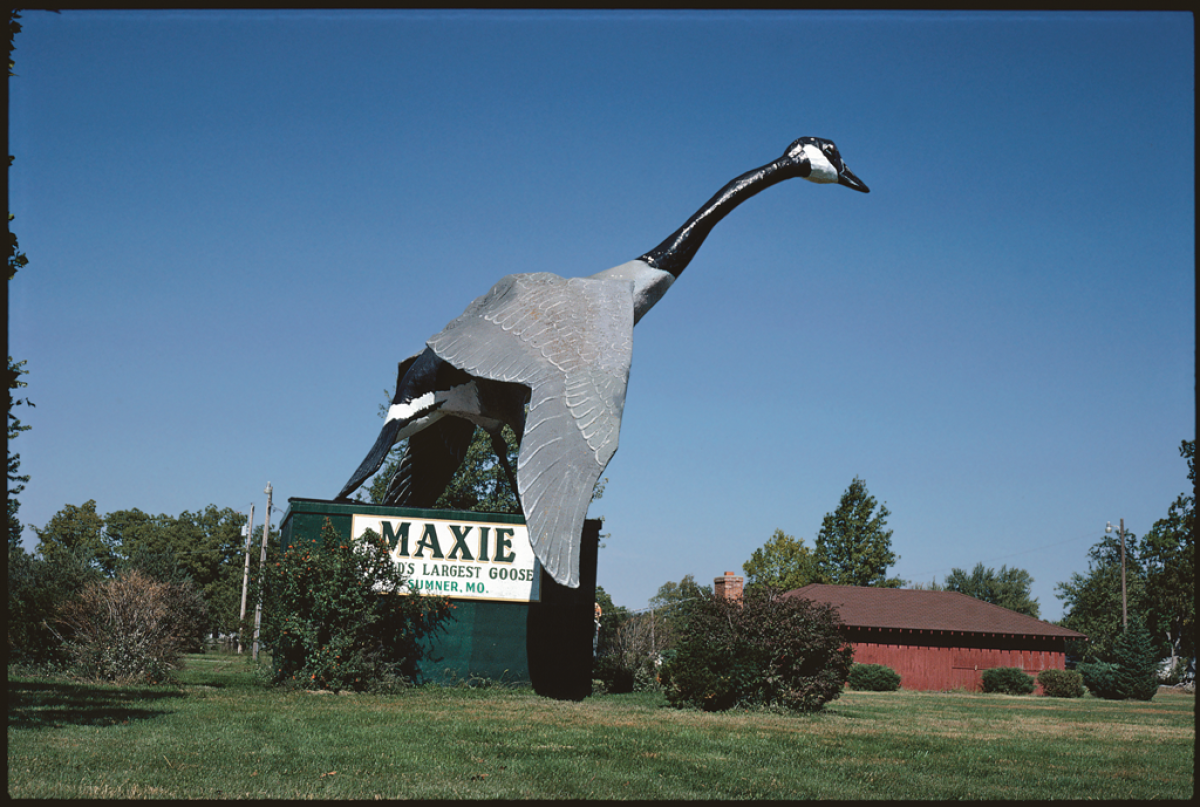

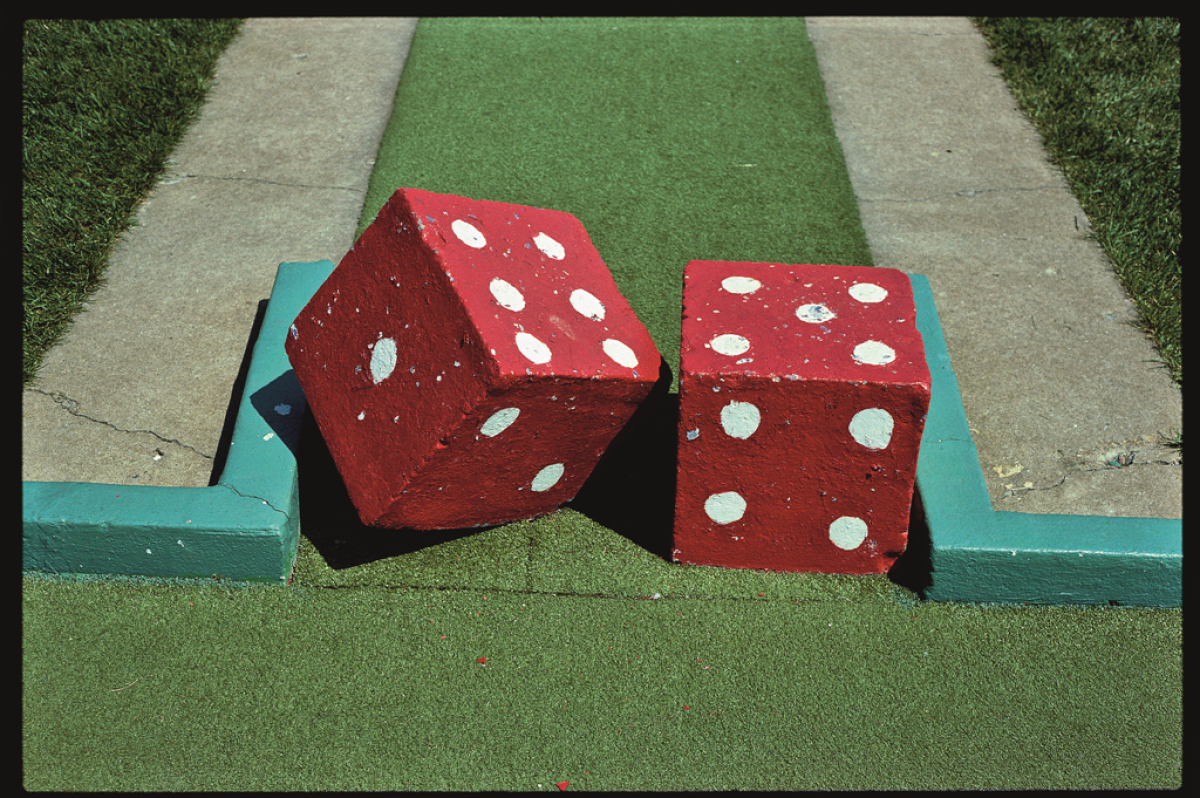

His books, including ”Roadside America,” “Home Away From Home” and “Pump and Circumstance,” delve lovingly into an America of neon signage, threadbare motels, sun-baked gas stations, faded resorts in New York’s Catskills, drive-in theaters, miniature golf courses, and all manner of vernacular architecture and design.

Through the decades, as his particular strain of nostalgia spread, his photos were chosen to anchor museum exhibitions across the U.S. and Britain, including the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich.; and the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C.

His collection of ephemera and other materials--postcards, matchbooks, menus, placemats, posters, felt banners--grew to such proportions that much the Library of Congress bought much of it, along with 13,000 of his images from the road. (We offer 22 of them here.)

There’s no telling how many road trips he inspired. And though his reverence for tepee-shaped motel rooms and Paul Bunyan statuary amused many a kitsch-loving reader, friends say there was nothing ironic or condescending in Margolies’ passion for these places.

“He never thought it was silly or kitsch,” said Margaret Engel, executive director of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and friend to Margolies for about 30 years. “He really felt that this was an expression of creativity that had to be grasped at 50 mph going down the highway – so of course everything was oversized and brightly colored and neon.”

Drawing on grants and fellowships from organizations including the National Endowment for the Arts, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the Patterson Foundation, Margolies started spending serious time on the road in the late 1970s and didn’t much slow down until the early 2000s, when his eyesight began to fail.

He used to sign postcards “Johnny Motel.” Now many of his favorite sights have been leveled, and his images are the best record we have.

“He had a lot of quirks,” said Jane Tai, Margolies’ companion of many years. “He carried a broom in his car, and he would do a little clean-up so that there wasn’t any extra debris in the frame….He would stay in a really bad motel, waiting for the weather to change, waiting for the shot that he wanted….He would stop traffic and lie on his belly.”

Engel said, “This was his life, this quest to catalog the entire country.”

Taschen America executive editor Jim Heimann, who worked with Margolies on “Roadside America,” said the author was “a surly but genuine guy and his passion for the roadside never abated.”

Heimann said he loved the time he spent sifting Margolies’ slides and “visiting him in his den of collectables.”

When not traveling, Margolies lived in Manhattan. But he was most fully alive, friends said, on the road.

Not that he was easy to please.

“John was extremely particular about what he would photograph and how he would do it,” said Engel, who joined Margolies on many trips in Virginia, Maryland and upstate New York.

“There couldn’t be any people or any cars. And he preferred very early morning light, as in 6 a.m. He would often pay people to move their cars. He really wanted pristine images.”

Karen Shatzkin, his attorney, said, ““He didn’t even want clouds in the sky.”

Margolies would be on the road for weeks or months. He used a yellow highlight pen to mark maps, often from the auto club. He liked to rent Cadillacs—in Tai’s words, “the biggest most American car he could get his hands on.”

He kept his slide film in a cooler so the colors would remain true. Another cooler held snacks. Instead of blowing his budget at tourist restaurants, he would buy a rotisserie chicken at the nearest grocery store.

When it came to lodging, he always wanted a room on the top floor – usually the second floor, because he mostly stayed in low-priced, two-story motor lodges.

He never wanted to be too close to the elevator, and he preferred having empty rooms on either side. He would always ask for two or three extra pillows in hopes that one might meet his specifications, Engel recalled.

He was never without big safety pins so he could pin his curtains closed. And he brought an extension cord with a nightlight attached so he could use it instead of turning on any bathroom lights. (Why? Because, Engel said, he hated that rasping sound motel bathroom fans make.)

And yet “he loved being on the road,” Engel said. “He loved meeting the people--even though he didn’t want them in his photographs. He loved mom-and-pop restaurants, and good barbecue.

“He was happiest when he was on the road.”

As the roadside lodging industry was perfected, Margolies once wrote, “The motel room evolved into a tone poem of shag carpets, indestructible furniture, indescribably predictable ‘great’ art on the walls and a heady aroma somewhere between eau de new car and Lysol wafting about the room.”

(In Los Angeles – where Margolies lived and taught early in his career—he loved the pre-renovation Clifton’s Cafeteria downtown and the grand old department stores along Wilshire Boulevard.)

On summer vacations, Tai and Margolies would take Lulu, their Cavalier King Charles spaniel, to Scott’s, a rustic, sixth-generation family resort on Oquaga Lake in the Catskills.

Sometimes Tai--a “Rothko kind of girl” who works at the Metropolitan Museum of Art--would find herself waiting for four hours while Margolies photographed “some godawful thing” like an elephant statue in a courtyard.

Although he had a master’s degree from the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, Margolies once said, “I wasn’t trying to make intellectual points. I wanted to go everywhere and see everything.”

In 2009, after the Library of Congress began buying his archive, Margolies gave a talk at the library that traced his passion back to early trips with family and friends. He especially remembered one journey from home in Stamford, Conn., to Orange Beach, Ala., when he was 13.

It was 1953. He made a list of all the brands of gasoline he saw advertised on the way. He realized that “I liked what was in the towns better than than what was between the towns.”

In fact, he told the Library of Congress audience, he went on to cover more than 100,000 miles in search of “deepest nowhere”– crisscrossing the Lower 48--without ever finding time for Yellowstone National Park.

Did Margolies have a favorite roadside haven? Perhaps Scott’s, in the Catskills. But this passage from “Home Away From Home” --about the quirky rooms and recurrent shocking pink hues of the Madonna Inn in San Luis Obispo–says a great deal about what motivated the author to drive all those miles, save all those postcards and snap all those photos.

“The Madonna Inn,” Margolies wrote, “is the grandest motel of them all, and it is the definitive expression of an individually owned and operated hostelry--light-years removed from the almost scientific sameness of the larger franchised chains….

“To the intellectual cognoscenti it can be understood and dismissed or enjoyed as kitsch. To amazed visitors who’ve probably never even thought of ‘design’ in formal terms, the Madonna Inn is a place full of joy, beauty, and one surprise after the next.”

ALSO

In the Black Hills, face-to-face — sorta — with Sioux leader Crazy Horse

$20 to $80 three-course dinners during Las Vegas Restaurant Week

Deal: Hotel Irvine throws in Fourth of July pool party with $129 rooms

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.