Late grandmother, NFL future power USC pass rusher Drake Jackson during ‘money year’

“Go get paid. Go get paid.”

As Drake Jackson burst around the edge two Saturdays ago, that message echoed through his mind. Here he was three games into a campaign he declared his “money year,” three weeks closer to his NFL future, and the talented Trojans pass rusher and possible top-10 draft pick had yet to record a sack.

Dating back to last season, it’d been six games since Jackson reached the quarterback. Over and over again, he’d come up just a half-yard short, a half-second slow — so close, coaches said, that there was little to criticize. It was only a matter of time, they assured.

Since he burst onto the scene as a freshman, Jackson has largely remained in that limbo, a half-step away from stardom. His extraordinary talent and tantalizing potential have kept him in the conversation as a top draft pick next spring. Despite tallying two sacks and 5.5 tackles for a loss last season, he was still named to the All-Pac-12 second team, partly in recognition of what he could accomplish at the height of his powers.

Each week, the Times’ national college sports reporter J. Brady McCollough picks the week’s eight best games, plus the USC and UCLA games.

For long stretches, Jackson seemed unable to fully access them.

Those powers were clear the moment he left Washington State’s left tackle in his dust in Pullman, Wash., closing the gap and colliding with the Cougars’ quarterback. The ball squirted out, a fumble was recovered by USC in the end zone and soon the rout was on.

It was a big moment for Jackson and a weight lifted off the shoulders of a USC pass rush that ranks 121st in the Football Bowl Subdivision in sacks ahead of a trip to face Colorado this weekend. But for the Trojans’ star pass rusher, it still didn’t feel like enough.

“I’m just a step late, a step off of having multisack games,” Jackson said Wednesday. “But I’m not there yet. Until I get there, until I have my multisack game, I’m not nothing.”

The stakes have certainly never been higher for Jackson, who says he’s pushing himself harder than ever to close the gap. Not, he says, for the money that awaits. Or the NFL scouts closely watching. But for his grandmother, Cynthia.

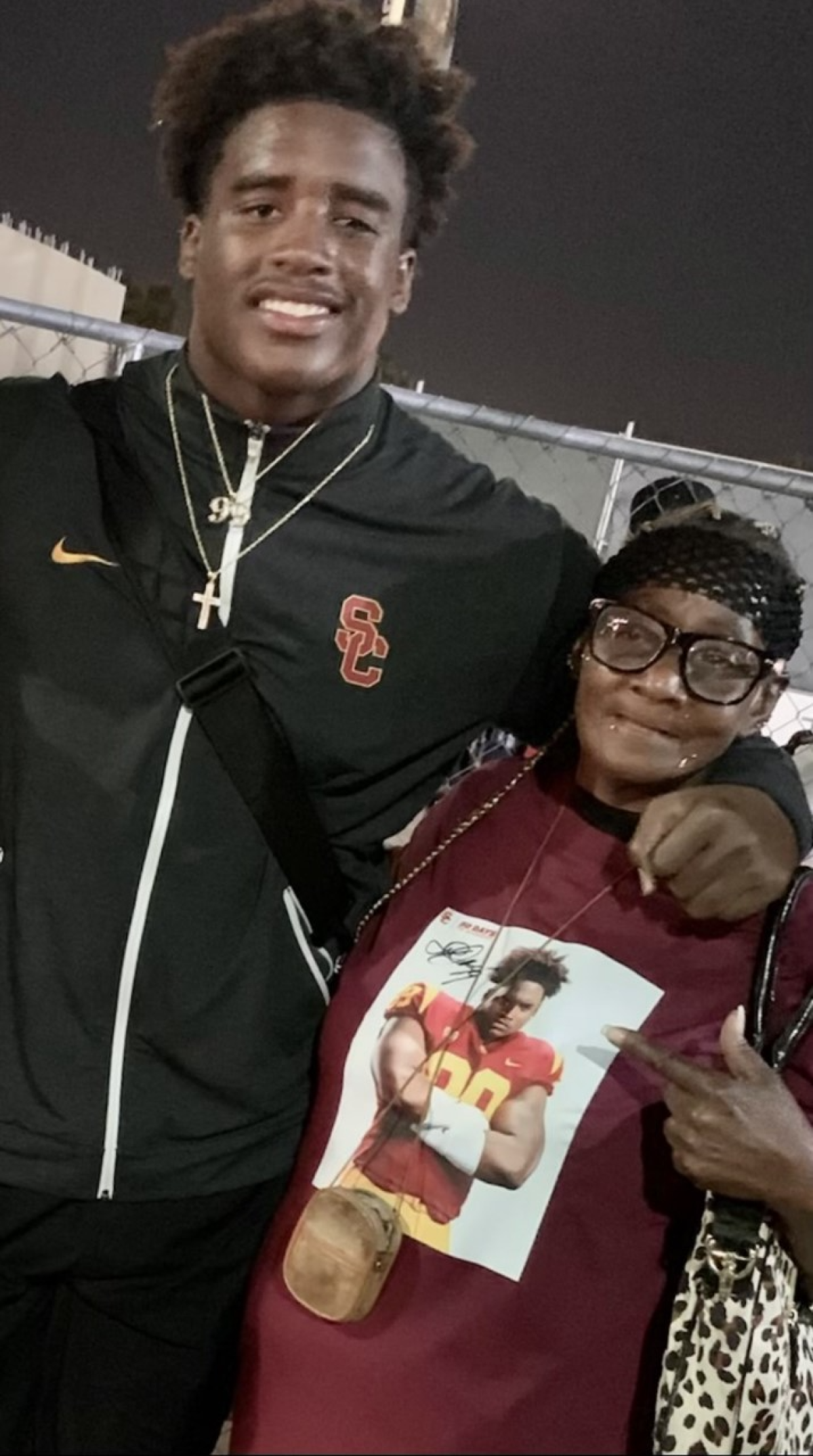

In a close-knit, big family, Cynthia Cavitt was the matriarch. Jackson says her lessons, imparted during summers spent at her house, helped propel him to this point.

“She’s the one who taught all of us how to work, how to be down and dirty, how to hustle,” Jackson said.

And she loved to follow her grandson’s budding football career. Pictures of Jackson playing football were prominently displayed around her house.

“Drake was her little celebrity,” said Dennis Jackson, Drake’s father.

And to her grandson, Cavitt was a constant presence. She was Jackson’s karaoke partner, ready to sing alongside him whenever the family gathered and a microphone was handy.

When he finally made the NFL, he’d planned to bring her along to the draft, to show her all that he’d accomplished. He thought about helping her out with his first big contract to pay her back for what she’d done for him.

But last March, Cavitt was killed after stepping in front of an oncoming train. Her son, Dennis, said she was attempting to stop the train after a dog ran onto the tracks. She was 67.

The unexpected loss was devastating for the family — and especially Jackson. One day his grandmother was there, the next she was gone. It still weighs on him six months later. When he thinks about his NFL future, he can’t help but think about her.

“She knew I was going to the league, but she didn’t get to see that through,” Jackson said. “That’s the reason I go. I know I have to make it.”

That goal powers him now, with USC sitting at 2-2, hoping to save its season before it’s too late. Jackson is a critical cog in that reclamation effort, the only Trojans pass rusher who’s proven capable of regularly getting to the quarterback. While he didn’t register a sack against Oregon State, he pressured the quarterback five times in the first half alone before sitting out most of the second with a minor groin injury.

This season, he’s had to pace USC’s pass rush while weighing 15 fewer pounds than planned. Forced to sit out for nearly three weeks after having his tonsils removed, then feeling symptoms after receiving the COVID vaccine, Jackson showed up to fall camp weighing 230 pounds, 35 pounds lighter than when he first arrived at USC as a freshman.

Jackson, who’s now around 245, says his lighter weight hasn’t adversely impacted him. But his father, Dennis, believes gaining that 10 pounds is the key to his son’s success.

With USC presumably looking for a big-name coach, the assumption was that Donte Williams had to perform a miracle to remove the interim label from his job description.

“I’m on him all the time,” Dennis Jackson said. “Like, ‘What are you eating? Sleep on these [protein] shakes, bro.’ But I’m not there anymore. At some point, he has to be his own man. He’s leaving the nest for real after the year.”

Jackson has at least eight games left in his “money year,”eight more opportunities to prove himself before focusing on earning a spot in the NFL. But as those chances dwindle, his grandmother’s words play over and over in his head.

“ ‘Gotta keep going, gotta keep going,’ ” Jackson said. “That’s what she would tell us.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.