Column: Why the A’s 30-year commitment to Nevada has a ‘Get Out of Vegas Free’ card

The pitch to the Nevada legislature was simple: If you provide the Oakland Athletics with $380 million in public funding toward a new ballpark, the A’s will agree to move to Las Vegas and stay there for at least 30 years.

The A’s got the funding. However, the agreement intended to bind the A’s to Las Vegas provides the team with an unusual escape clause: If ever a tax is aimed at the A’s, the team can leave town without penalty.

“That is not a normal clause in these things,” said Martin J. Greenberg, the founder of the National Sports Law Institute at Marquette University Law School and an expert in so-called non-relocation agreements in Major League Baseball.

“The whole object of this is to keep the team at home.”

This is not on the A’s. The Las Vegas Stadium Authority approved such a provision in luring the Raiders and presented virtually identical contract language to the A’s.

A Nevada Supreme Court ruling issued Monday said the Athletics can proceed with plans for their proposed Las Vegas ballpark without worrying that voters might repeal $380 million in public funding.

“It is a targeted tax clause that says if they are taxed in a way that is different than the way other businesses are taxed, they have the option to leave,” said Erica Johnson, director of communications for the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.

This is not some remote hypothetical. If you go to a show in Las Vegas, you pay a 9% live entertainment tax. If you go to a game in Las Vegas — and the game is staged by a pro team based in Nevada — you do not pay that tax.

In 2021, an effort to remove that professional sports exemption was rejected. During legislative hearings on the A’s funding last summer, a state senator asked A’s President Dave Kaval whether the team would be willing to pay the tax, given that smaller Nevada businesses do. The Raiders and NHL Golden Knights do not.

Kaval dodged a yes or no answer, saying only that the legislation did not contemplate that. In the future, should a specific tax target the A’s, their players or opposing players, the A’s can move out of town.

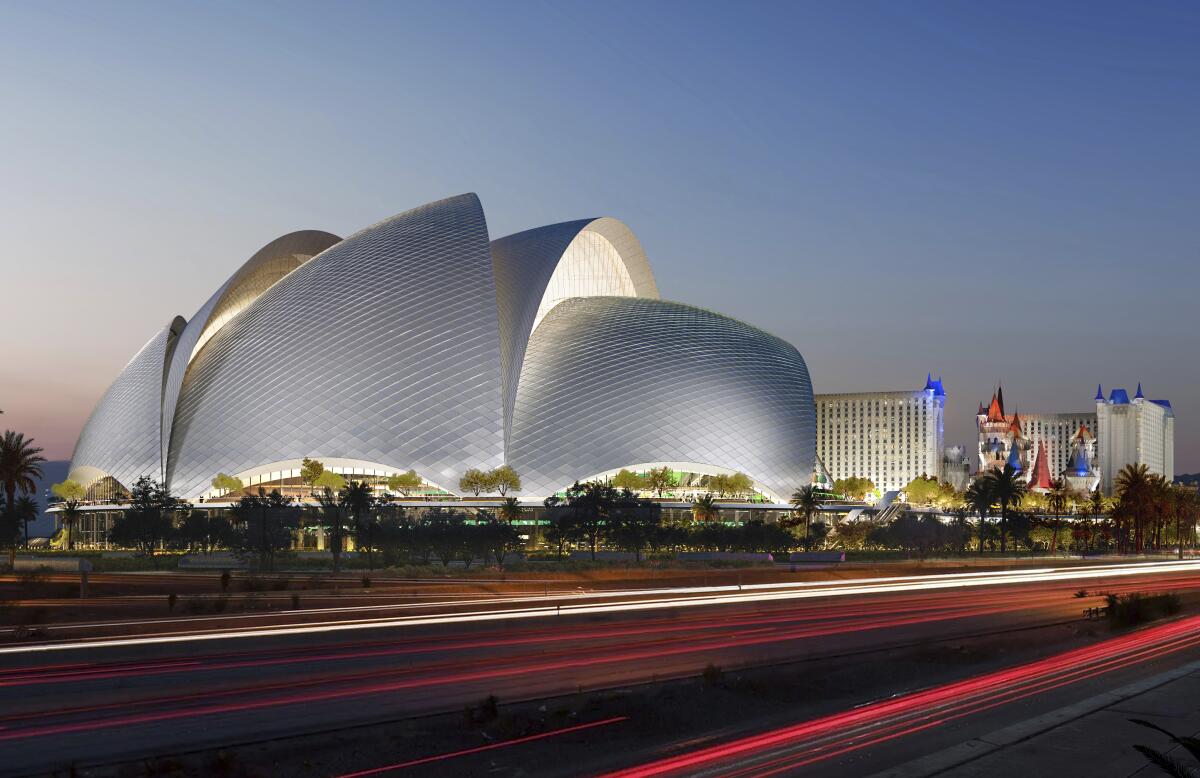

The A’s propose a 33,000-seat ballpark in Las Vegas. If the A’s sell 26,000 tickets per game at last season’s average major league ticket price of $37, a 9% tax could generate $7 million for Nevada per year.

In a presentation led by Steve Hill — chairman of the stadium authority and president of the visitors authority — the Nevada legislature was told the A’s could generate an estimated $1.3 billion per year in economic impact. (Most economists consider this estimate wildly optimistic.)

I asked Johnson why the A’s would be provided with an opt-out clause that could jeopardize that economic impact. She did not comment. Hill was unavailable for comment.

“These non-relocation agreements are what I call political cover,” Greenberg said. “They basically are, at least from a politician’s standpoint, the quid pro quo for the gigantic amount of public dollars that are going into these stadiums.

“Basically, the politician can say, ‘Look, we’re investing all this money because the team is going to stay here, based upon a non-relocation agreement.’ ”

In 2022, the Anaheim City Council considered such a targeted tax — a 2% admission tax that would have applied only to Disneyland, Angel Stadium and the Honda Center, where the NHL Ducks play. The council ultimately voted against the tax, in part because the Angels’ lease requires the city to credit the amount generated by any such targeted tax at Angel Stadium against the team’s rental payments.

The leases of the Colorado Rockies and Seattle Mariners restrict the ability of the respective stadium authorities to impose any targeted taxes. The Miami Marlins’ lease restricts the city or county from imposing a targeted tax and empowers the team to sue if it believes a tax violates the agreement.

David Samson, the former Marlins president who negotiated that lease, said it is impossible to protect against any targeted tax that might be imposed at any level of government at any point in the future. What a lease can do, he said, is say what can happen in the event such a tax is imposed.

“Can be anything,” Samson said, “a rent abatement, some sort of extra flow of funds from general revenue, or it can be as far as, hey, this non-relocation agreement becomes null and void.”

The Oakland Athletics hire Galatioto Sports Partners to attract $500 million in private investing for their proposed stadium on the Las Vegas Strip.

I asked Johnson if any alternative language had been considered besides granting the A’s the ability to move. She did not comment.

For the record, neither Greenberg nor Samson believes Las Vegas would be at high risk of losing the A’s if a targeted tax were to be imposed. For one, although the A’s would have the option to relocate, they could choose not to do so, or negotiate a lease concession in exchange for not doing so.

If the team did wish to move, it would have to find a new home, secure funding for a new ballpark there, and win a vote among MLB owners — and the saga that led to Las Vegas took two decades for the A’s. Their move to Las Vegas would be only the second MLB relocation since 1972.

“It’s not easy, as we’ve seen, to move a team,” Samson said.

It’s also not easy to build a fan base in a new city. It might be a little bit easier if the “We’re here for 30 years!” pledge were not accompanied by an asterisk.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.