Rachaad White never envisioned himself here. Outside in the sweltering summer heat on a Saturday afternoon in 2018. Standing on a street corner outside of a Toys R Us parking lot, Young Thug bumping through his earphones as he held up a sign that read “70% OFF: GOING OUT OF BUSINESS” in bold letters.

It wasn’t a job he enjoyed. But it paid him on the same day, which often meant he and his teammates could afford their next meal. White had to be out there.

“It was tough,” he said. “I didn’t like it, but I understood what I had to do in order to get to where I was trying to go.”

Just a few months earlier — and years before he became the starting running back for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, who play at the Detroit Lions in an NFC divisional round playoff game Sunday — White arrived at Mount San Antonio College in Walnut, to chase his dream of being a Division I football player. But junior college football in California comes with its own set of challenges.

The California Community College Athletic Assn. (CCCAA) doesn’t allow football programs to offer scholarships. Players are on the hook for tuition, and out-of-state players such as White, who transferred in from the University of Nebraska-Kearney, had to pay out-of-state tuition until they could establish residency. There also aren’t any dorms, leaving athletes to find and pay for their own housing.

Patrick Mahomes and the Kansas City Chiefs are used to playing in the postseason at home, but Sunday’s game against the Bills will offer a new challenge.

“Tuition for junior college should be cheap, but with us being from out of state it costs more money,” said Zach Curry, a former defensive end for the Mounties. “So guys were paying $5,000, $6,000, $10,000 just to go to class for that semester.”

Curry remembers returning to his apartment after workouts one day in the spring to find White moving in along with two friends from his hometown of Kansas City. With their arrival, 16 people now shared that two-bedroom apartment. White slept on the living room floor with four of his teammates. It was a far cry from where he was just one semester before that.

White had drawn interest from Division I schools such as Iowa and Iowa State. Coaches even visited his high school to meet him, but he ultimately never received any offers. On the advice of his coach, White took a “safer route” with his degree in mind and settled on Nebraska-Kearney, a Division II school. But once White took the field, it became clear to his teammates he was on another level.

One day during practice, White carried the ball on an inside zone run. As the freshman hit the hole, junior linebacker Kevin Wilson had a clear angle to him from the backside. He didn’t even need to wrap him up, Wilson had a big hit in mind as he closed the gap. But without even looking his direction, White stiff armed Wilson to the ground, who watched the rest of the play from his knees as White ran into the end zone.

Wilson went up to White after practice that day and told him, “You need to leave.”

Later that night, Wilson called up Junior Tanuvasa, his former linebackers coach at Mount SAC, to tell him about this running back who he had nicknamed “Young Le’Veon,” a reference to former Pittsburgh Steelers running back Le’Veon Bell, and how he was “too good to be here.” Tanuvasa watched some practice film, and he knew right after the first play that White was a Division I running back, potentially even an NFL running back. He then got White on the phone to talk him into leaving Nebraska-Kearney, where he had a partial scholarship, and bet on himself at the junior college level.

But the main point Tanuvasa wanted to convey to White was the reality that junior college athletes face. Tanuvasa had played at Mount SAC, so he wanted White to know what to expect. Tanuvasa told White about having to live in an apartment with a bunch of other guys, having to work odd jobs just to afford to pay his bills and that any financial aid he might get would go toward his tuition.

“You really have to believe in yourself to be able to do that and be successful,” Tanuvasa said. “There’s guys that’ll go down to junior college and think that they want to, until they actually show up and have to work through it.”

White trusted Tanuvasa, Wilson and some of his other Nebraska-Kearney teammates who had also played at the junior college level and shared their experiences with him. He went to California and ended up at Mount SAC after Tanuvasa had left to take a job at Dixie State University (now Utah Tech). But Tanuvasa knew he’d be in good hands.

Mount SAC is a football powerhouse in California. Former Seattle Seahawks defensive end Bruce Irvin, former Tennessee Titans tight end Delanie Walker and former New York Giants linebacker (and current Las Vegas Raiders head coach) Antonio Pierce all played for the Mounties, and their pictures adorn head coach Bob Jastrab’s office, along with two national championship and three state championship trophies. The bar for excellence at Mount SAC is set high, but once White put on his pads and began practicing with the Mounties during preseason camp, Jastrab realized what he had.

The Chargers should do everything possible to land Jim Harbaugh as their new head coach, writes L.A. Times columnist Bill Plaschke.

Standing 6 feet, White was big for a running back. Bigger than most that his junior college teammates had seen. Some of them even thought he’d eventually switch to playing defense because of his size.

But then they saw what made White special. Safety D’Ondre Robinson, who had a reputation as a big hitter, was one of the Mounties’ leaders in 2018. Robinson always practiced at full speed, crashing into the ball carrier every chance he got. Except for White.

It’s not that he took it easy on White, he just couldn’t hit him. White was too fast, too shifty; he was always able to move his body in just the right way, able to change direction just quickly enough to make Robinson miss.

“It was always hard to get a direct hit on him, so he kind of frustrated me. Like I can’t hit him the way I want to,” Robinson said. “And I tried. Best believe, I tried.”

Sanu Baraka, a former linebacker for Mount SAC, knew White was different from his peers after one play. Baraka got past the offensive line and into the backfield on a blitz. He had a perfect angle on White, but he ended up on the receiving end of a stiff arm as the play was blown dead. No matter what the defense did, White was always ahead of them.

“His IQ, his awareness, it was at a different level at the time. Like yeah, we were all good, but Rachaad just stood out in certain aspects from all of us,” former Mount SAC cornerback Treshon Pickett said. “All of our DBs at the time … we were all running full force, and we still couldn’t catch Rachaad.”

While White had earned the respect of his teammates, he struggled to learn a new scheme, had trouble picking up blocking assignments and had to figure out how to be more of a threat in the passing game. He ended up spending most of his freshman season as the third-string running back.

The Mounties rarely lost more than a few games in a season, but the 2018 team was a particularly young and inexperienced group, and it showed later in the season when the team had a three-game losing streak. As the losses mounted, Robinson and Baraka pounded the table for the coaches to give White more carries. Tanuvasa, who had been watching the season unfold from afar, called offensive coordinator Bobby Purcell to tell him to get the ball to White.

Whether with Cal, the Rams or the Lions, quarterback Jared Goff has proven to be the impetus behind bad teams turning great as Detroit ousts Rams.

White finally received an opportunity during a Week 8 loss to Cerritos College, when he put up 114 yards and a touchdown, the first of his college career, in four carries. The following week, White helped end the Mounties’ losing streak in quadruple overtime when he took a handoff from the five-yard line, ran to the outside, cut inside to avoid a tackle and dove into the end zone for the winning touchdown.

White never got too upset about how long it took to earn carries.

“I did have my times where you doubt yourself, but that just goes with the sport,” White said. “But I had some good dudes in my corner, some great friends in my corner that helped me through them times.”

There was a noticeable shift in White going into his second year. Cameron Deen, quarterbacks coach and co-offensive coordinator, noticed how much White improved. He was more of a complete back in the style of Christian McCaffrey and Bijan Robinson. He ran routes with the receivers. He would sit in on film sessions with the quarterbacks, telling them to check it down to him if their reads weren’t there.

“His game elevated very quickly and his confidence developed,” Deen said. “He knew that he could dominate when he wanted to and going into that sophomore year, there was no stopping him.”

White’s mindset was that he needed to get out of junior college, and he didn’t put himself through all of this just to return to Division II. He couldn’t let himself down.

“I didn’t really have no Plan B,” he said. “I can’t go back home to my family and let them down and not put on a show.”

As a sophomore, White put up 1,480 all-purpose yards and 14 total touchdowns, averaging 6.4 yards per carry. He was named a first-team All-American by the CCCAA Football Coaches Assn. and was ranked as the third-best junior college running back in the nation by 247Sports.com.

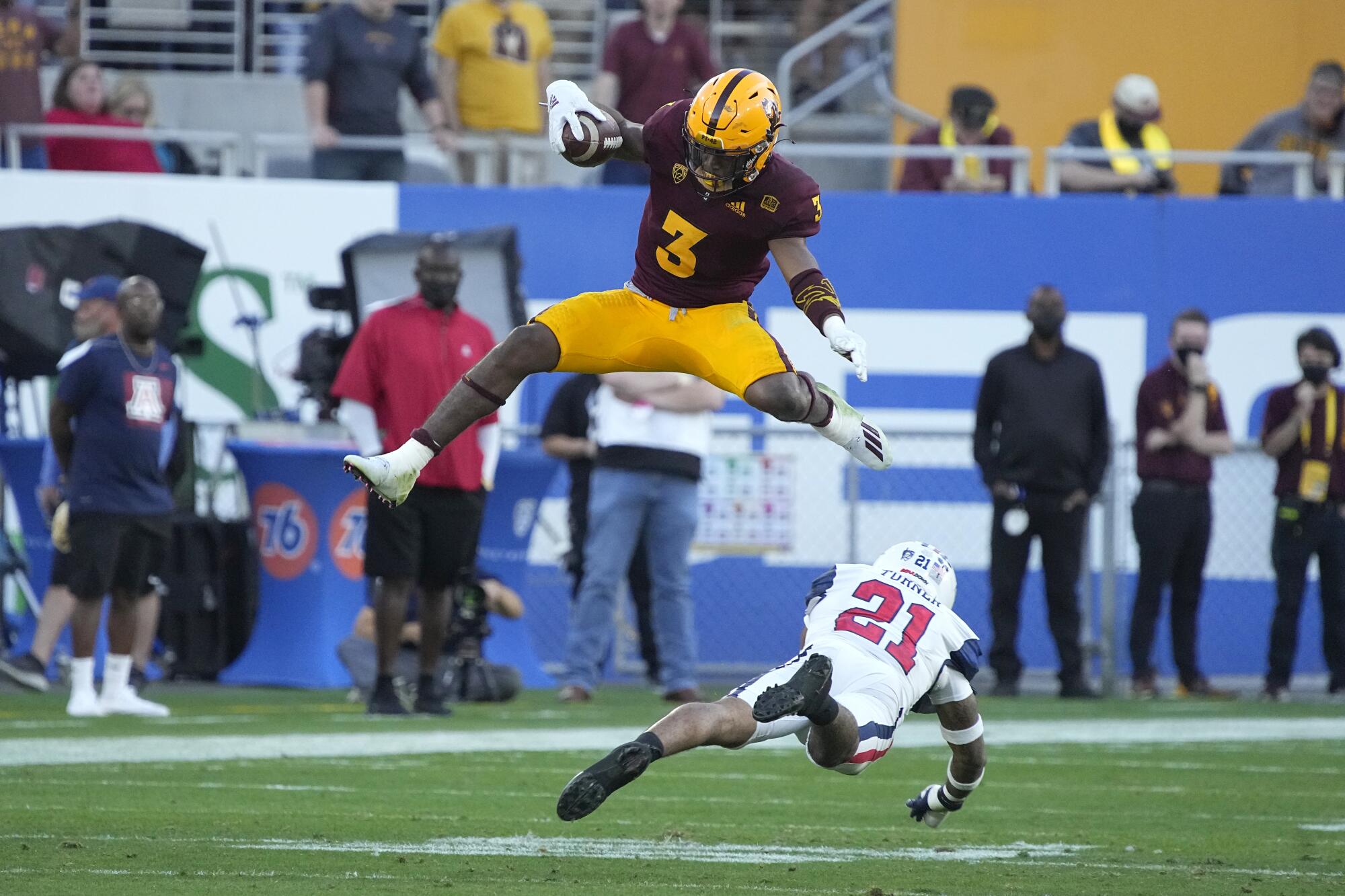

White eventually signed with Arizona State, where he would star for the Sun Devils before he was selected in the third round of the 2022 NFL draft by the Buccaneers. For White’s Mount SAC teammates, seeing one of their own reach the NFL made everything they went through worth it.

“He’s one of those Sacdawgs that bet on himself, and that bet came to reality,” Robinson said. “I just remember him as a skinny, goofy ... running back and now he’s a father and an NFL star. … I just love the man that he’s becoming, what he’s been through, and where he’s at now.”

White calls his time in junior college the most crucial part of his journey to the NFL playoffs.

“It was hard and stuff like that, but I don’t regret it for nothing,” he said. “Even if I couldn’t get the same outcome, I would do it all over again because it just helped me be who I am today as a man. And that’s the biggest thing I care about.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.