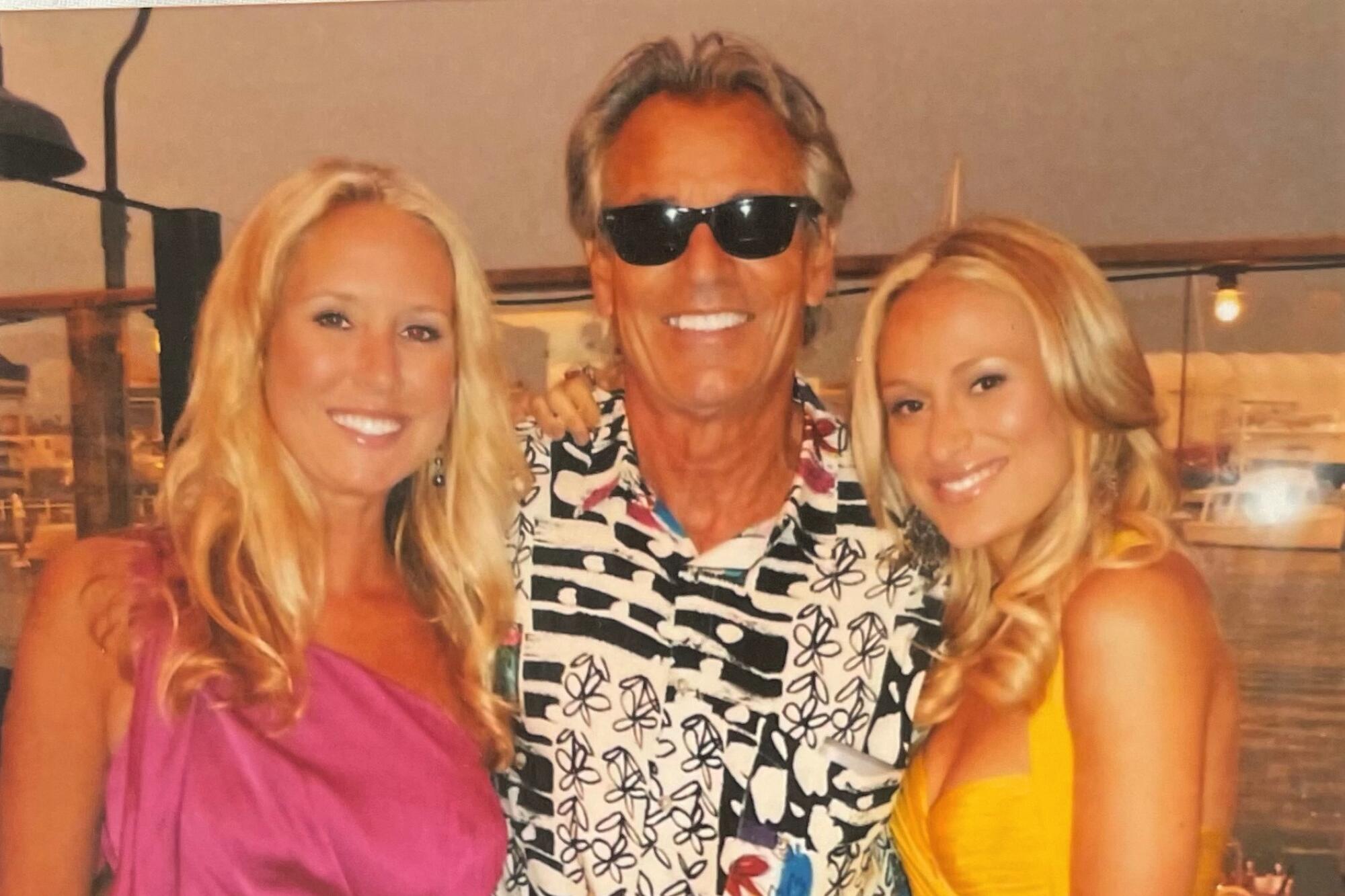

Bob Thate, the Beamer-driving, Ray-Ban wearing coach with the flowing hair and the SoCal swag was actually a bit of an introvert. But this was his element — on a basketball court about to teach.

The story goes something like this:

Thate was excited for the chance to talk to kids at one of Kobe Bryant’s basketball camps, but he wasn’t sure what he’d say. Bryant was one of his favorite players, someone as maniacal about the processes involved in becoming as great as Thate.

Thate wanted to get it right and, eventually, he settled on an icebreaker.

“Here are the five best basketball players I’ve ever seen with my own two eyes,” he told the campers. “No. 1, Kobe Bryant.”

The campers roared.

“No. 2,” he said, “Michael Jordan.”

More cheers.

“No. 3, you might not have heard of him, but Wilt Chamberlain. And No. 4, that’s my guy, Jerry West.”

Finally, one camper raised his hand to ask the obvious question to the coach.

“What about No. 5?”

The trap was set.

“You’re looking at him,” Thate deadpanned.

The story was retold Wednesday in San Clemente, blocks from the beach by former Pepperdine coach Gary Colson at Thate’s funeral service.

Like most men, I can bury a wad of dirty socks in the hamper from 30 paces. Swish.

Former Clippers star Blake Griffin stood on the back of the lawn. Luke Walton sat in one of the last rows of white chairs with his mother. Former No. 3 overall draft pick Jahlil Okafor had a seat on the end of another row. All of them listened to stories about Thate, a critical thread in Los Angeles’ basketball history that operated mostly in anonymity.

Thate died on June 8 from complications related to COVID-19. He was 76.

He’d fought multiple battles with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the previous handful of years.

The kids at the Kobe Bryant camp can be forgiven if they didn’t know who they were about to hear from, but these NBA players — and many more — absolutely knew Bob Thate.

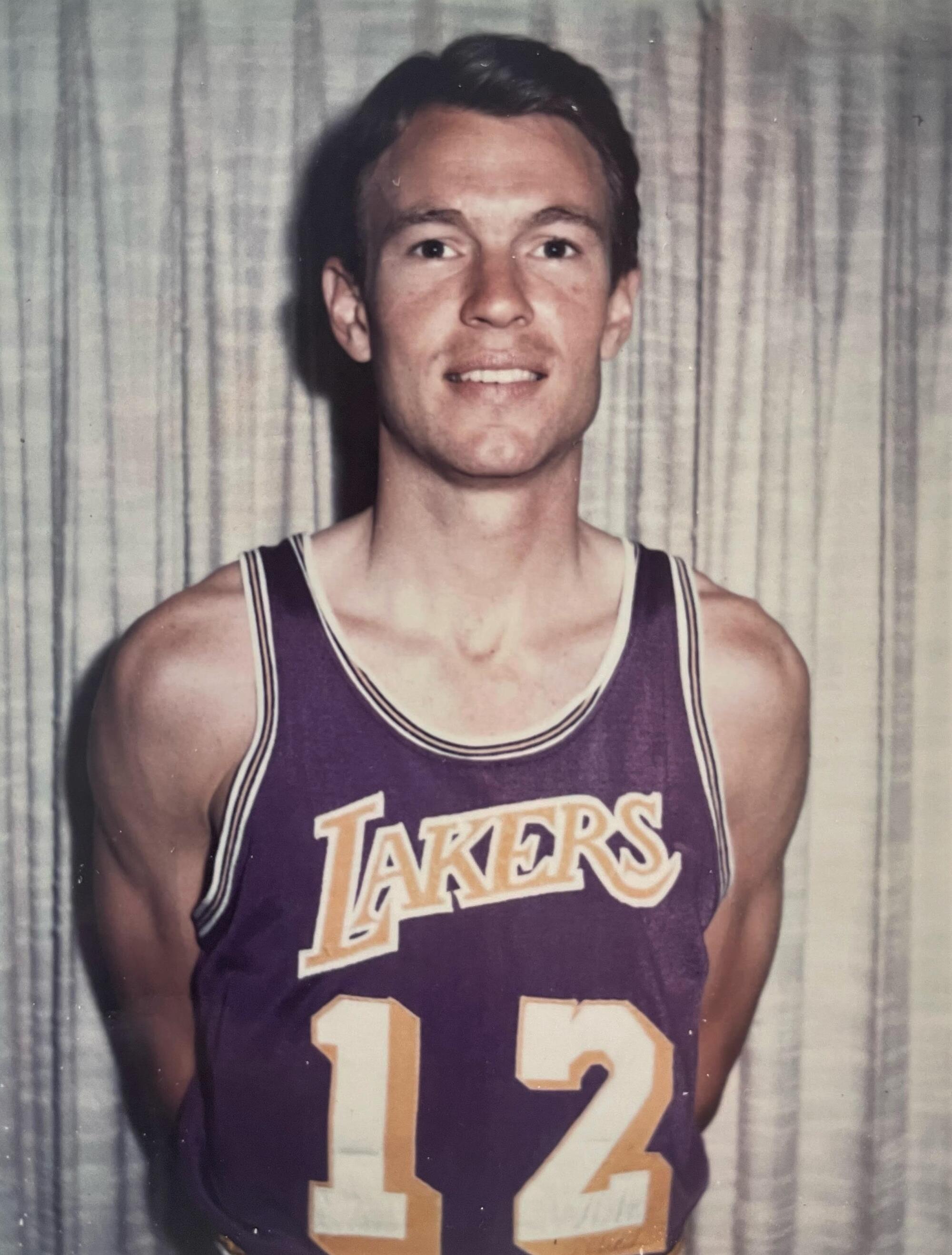

His daughters Taylor and Ali knew best. They knew they were being raised by a basketball savant, one good enough to lead Los Angeles high schools in scoring before going to USC on a basketball scholarship. They heard how a Trojans coaching change pushed him out to Division III Occidental College, where he became a two-time All-American.

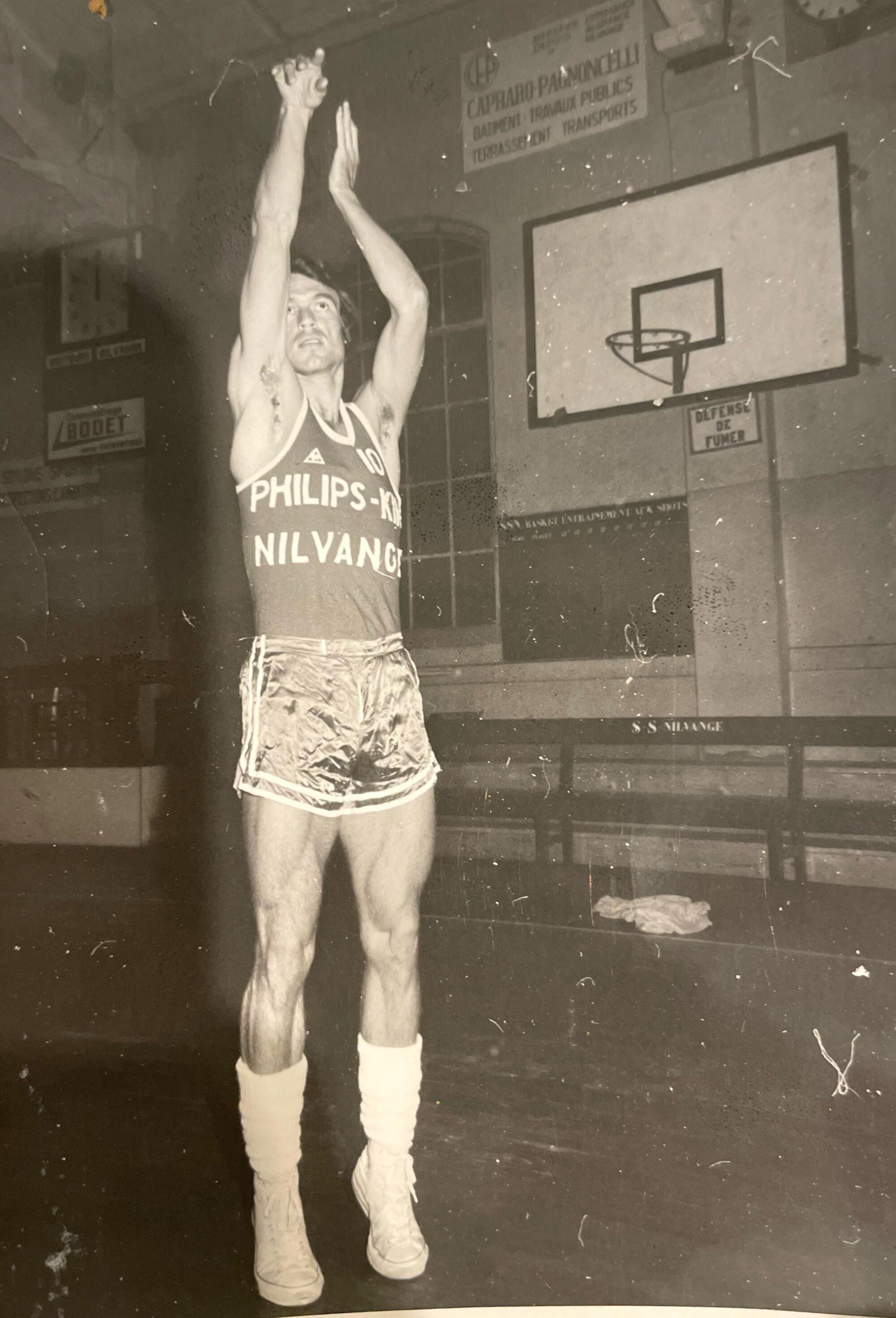

They eulogized him near a photo of Thate in a Lakers uniform taken after he was drafted by his hometown team in the 17th round of the 1970 NBA draft. After he was cut in training camp, he played in France and set scoring records in professional leagues abroad.

He averaged 43 points one season and nearly 39 another — the highest average in the history of France’s top league. This past season, Victor Wembanyama, the best NBA prospect since LeBron James, averaged 21.6 points.

Thate scored a Bryant-esque 74 one night and earned the nickname “artilleur” — French for “gunner.”

On a recent appearance of Bill Cartwright’s podcast, Thate self-deprecatingly said his scoring records meant he just shot a lot.

He returned to coach college basketball at Pepperdine, Long Beach State and UC Irvine. He earned a reputation as a top-notch recruiter and talent scout before settling in at Santa Ana Foothill High School in 1993 to coach boys’ basketball and spend more time with his girls. They’d spend afternoons at Disneyland and loved seeing their father, a real-life embodiment of Peter Pan, in his element at the theme park where magic was all around.

On the court, in the eyes of so many people in basketball, Thate was the source of his own wizardry. After pausing his college coaching career to spend more time with his daughters, big-time basketball kept finding him. Former Jazz and Lakers guard Bryon Russell sought out Thate’s help after the two worked together in Long Beach. Seeing the results of his teammate, Luke Walton quickly became a disciple in his rookie season. Later, so would NBA stars Jason Kidd, Blake Griffin and Mike Miller — cementing Thate as one of the best shooting coaches in the profession.

“Whatever he did,” his daughter, Taylor, said, “it always worked.”

To work on shooting with Thate meant you had to be prepared to be humbled, to have the skill you used to achieve success and riches completely deconstructed. Griffin compared it to having a prized car stripped for parts right in front of your eyes, leaving players totally exposed.

“The worst,” Griffin said. He felt like he didn’t know how to shoot, a skill he owned in some form since childhood now as familiar as a foreign language.

Walton said he’d shout at Thate to “shut up” with some colorful language sandwiched in between.

It wasn’t for everyone. Partnerships with Shaquille O’Neal and DeAndre Jordan didn’t work out, the process too severe for partial commitment.

Griffin used to kick basketballs all over the gym out of frustration when he couldn’t get it right. For more than a year, he and Thate broke apart all of Griffin’s bad habits and rebuilt a jump shot piece by piece.

Thate, an assistant coach for the Clippers in 2015-16, would watch games in the tunnel, usually in sweats and a polo or long-sleeved T-shirt, his arms crossed. He said at the time his focus would almost entirely be directed on Griffin’s form — the movement of the nine other players and the action happening around the game irrelevant.

After leaving the Clippers, he went to work for the Memphis Grizzlies. He still worked closely with former UCLA star Kyle Anderson, though a lot of the work happened via FaceTime because Thate was immunocompromised after his cancer battle. He had been doing the same with Okafor.

The players who bought in had to tear apart and rebuild their shots at the same time they needed to perform in NBA games, requiring humility, bravery and commitment all at once.

It was a rough job — one rooted in leading players through more failure than they were used to. But Thate loved it, loved the process, the teaching and the gratification he got from seeing others succeed.

Walton shot 38.7% from three-point range in his fourth season with the Lakers. Kidd became a 37% three-point shooter in the final eight years of his career and is 15th all-time in made threes. Griffin eventually became a mid-range star and a high volume three-point shooter — he made 36.2% on seven attempts per game in 2018-19.

Like Taylor said, her dad always made it work.

Maybe that’s why all of this has shocked them — that someone could beat lymphoma twice only to catch and succumb to COVID.

“What the hell just happened?” Taylor has wondered over and over again for the last month.

Some of those answers will never come. Others were answered last week as Thate’s family, friends, colleagues and players all gathered to celebrate the impact he’d made on them.

Because for how good of a player Thate was — one of the five best he admittedly ever saw — he did more as a coach, as a father, as a grandpa.

And while he’s gone, his impact will continue to be felt.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.