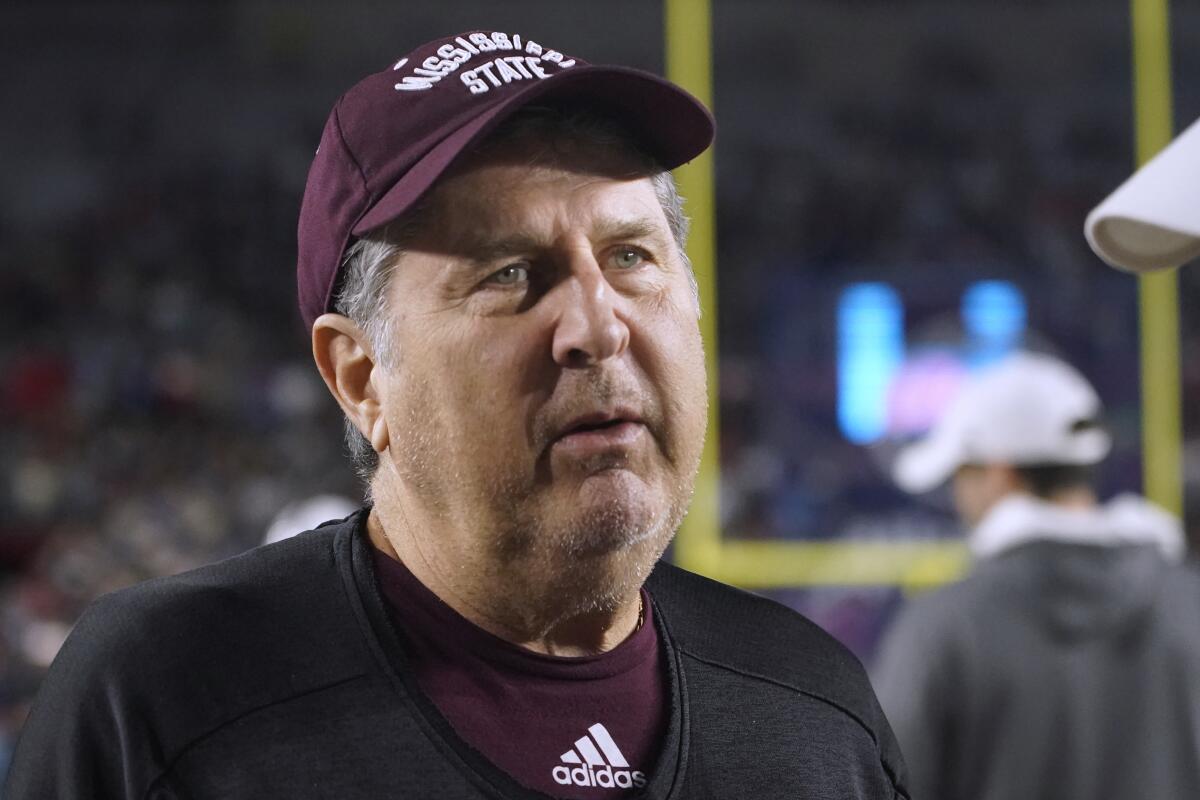

Pioneering college football coach Mike Leach dies at 61

Mike Leach, the gruff, pioneering and unfiltered college football coach who helped revolutionize the passing game with the Air Raid offense, died Monday night following complications from a heart condition, Mississippi State said Tuesday. He was 61.

Leach, who was in his third season as coach at Mississippi State, fell ill Sunday at his home in Starkville, Miss. He was treated at a local hospital before being airlifted to University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, about 120 miles away.

Leach fought through a bout with pneumonia late in this season, coughing uncontrollably at times during news conferences, but seemed to be improving, according to those who worked with him.

News of him falling gravely ill swept through college football the last few days and left many who knew him stunned, hoping and praying for Leach’s recovery.

College football coaching great Mike Leach was known for his colorful stories and vast coaching tree, but his greatest gift might have been curiosity.

Leach, who was a college football head coach for 21 years, is survived by his wife, Sharon; children Janeen, Kimberly, Cody and Kiersten; and extended family.

“Mike was a giving and attentive husband, father and grandfather. He was able to participate in organ donation at UMMC as a final act of charity,” the family said in a statement issued by Mississippi State. “We are supported and uplifted by the outpouring of love and prayers from family, friends, Mississippi State University, the hospital staff, and football fans around the world. Thank you for sharing in the joy of our beloved husband and father’s life.”

His impact on college football during the last two decades runs deep and will continue for years to come.

Leach’s teams were consistent winners at programs where success did not come easy. In 21 seasons as a head coach at Texas Tech, Washington State and Mississippi State, Leach went 158-107. And his quarterbacks put up massive passing statistics, running a relatively simple offense called the Air Raid that he did not invent but certainly mastered.

USC coach Lincoln Riley was among those paying tribute to Mike Leach, who died Monday night. Leach’s vast coaching tree included Riley and many others.

USC coach Lincoln Riley has long credited Leach for igniting his coaching career.

Riley, who has coached three quarterbacks to Heisman Trophy wins, struggled to earn any playing time as a reserve Texas Tech quarterback. He knew the offense better than anyone else, but a shoulder injury he suffered his senior year at Muleshoe (Texas) High limited his effectiveness throwing the ball. Riley was likely to be cut ahead of the 2003 season, so Leach asked the 19-year-old to join his coaching staff as a student assistant.

Riley made the most of the opportunity to soak up essential traits of Leach’s Air Raid offense, fast-tracking his ascent as a young college football coaching star.

Riley posted on Twitter on Tuesday morning: “Coach - You will certainly be missed, but your impact on so many will live on. - Thankful for every moment. You changed my life and so many others. All of our prayers are with Sharon & the Leach family - Rest In Peace my friend.”

Texas Christian coach Sonny Dykes, whose team will compete in the College Football Playoff semifinals, also honed his skills on Leach’s staff.

“It’s hard to put into words the impact that Mike Leach had on the players he coached, the game of football and me personally,” Dykes posted on Twitter. “He was a unique personality and independent thinker and a great friend. No one had a greater influence on my life other than my father.”

In Starkville, under gray skies, the videoboard at Davis Wade Stadium showed an image of a smiling Leach and the message: “In loving memory.” Black ribbons were tied to the stadium gates and flowers were left there to honor the coach.

“Mike’s keen intellect and unvarnished candor made him one of the nation’s true coaching legends,” Mississippi State President Mark Keenum said. “His passing brings great sadness to our university, to the Southeastern Conference, and to all who loved college football. I will miss Mike’s profound curiosity, his honesty and his wide-open approach to pursuing excellence in all things.”

At Martin Stadium in Pullman, Wash., a similar tribute was on the videoboard above a snow covered field.

USC coach Lincoln Riley has molded his version of the Air Raid offense throughout his career, adjusting it to best fit his personnel each year.

Leach was known for his pass-happy offenses, wide-ranging interests — he wrote a book about Native American leader Geronimo, had a passion for pirates and taught a class about insurgent warfare — and rambling, off-the-cuff news conferences.

An interview with Leach was as likely to veer into politics, wedding planning or hypothetical mascot fights as it was to stick to football. He considered Donald Trump a friend before the billionaire businessman ran for president and then campaigned for him in 2016.

He traveled all over the world and most appreciated those who stepped outside of their expertise.

“One of the biggest things I admire about Michael Jordan, he got condemned a lot for playing baseball. I completely admired that,” Leach told the Associated Press. “I mean, you’re gonna be dead in 100 years anyway. You’ve mastered basketball and you’re gonna go try to master something else, and stick your neck out and you’re not afraid to do it, and know that a lot of people are gonna be watching you while you do it. I thought it was awesome.”

Six of the 20 best passing seasons in major college football history were by quarterbacks who played for Leach, including four of the top six.

Calling plays from a folded piece of paper smaller than an index card, Leach turned passers such as B.J. Symons (448.7 yards per game), Graham Harrell (438.8), Connor Halliday (430.3) and Anthony Gordon (429.2) into record setters and Heisman Trophy contenders.

“You have to make choices and limit what you’re going to teach and what you’re going to do. That’s the hard part,” Leach told the AP about the Air Raid’s economical playbook.

Leach also had a penchant for butting heads with authority, and he wasn’t shy about criticizing players he believed were not playing with enough toughness.

In two seasons as Oklahoma’s coach, Lincoln Riley has had two quarterbacks win the Heisman Trophy. Jalen Hurts could be next for the Sooners.

A convergence of those traits cost Leach his first head coaching job. He went 84-43 with Texas Tech, never having a losing season at the Big 12 school and reaching No. 2 in the nation in 2008 with a team that went 11-2 and matched a school record for victories.

He was fired by Texas Tech in December 2009 after being accused of mistreating a player, Adam James — the son of former ESPN announcer and NFL player Craig James — who had suffered a concussion.

He refused to apologize for the conflict and eventually sued Texas Tech for wrongful termination. The school was protected by state law, but Leach never stopped trying to fight that case. He also filed a lawsuit against ESPN and Craig James that was later dismissed.

While out of coaching for two seasons, Leach and his wife, Sharon, retreated to their home in Key West, Fla., where he rode his bike around town and knocked back drinks at the bars.

He returned to coaching in the Pac-12 Conference but never gave up that beloved home in the Keys.

Leach landed at Washington State in 2012. After three losing seasons, the Cougars soon looked very much like his Texas Tech teams. In 2018, Washington State went 11-2, setting a school record for victories, and was ranked as high as No. 7 in the country.

Leach moved to the SEC in 2020, taking over at Mississippi State. After years of questions about whether Leach’s spread offense could be successful in the nation’s most talented football conference, the Bulldogs set an SEC record for yards passing in his very first game against defending national champion Louisiana State.

Mississippi State hired Washington State’s Mike Leach as head coach, bringing one of the nation’s quirkiest and most successful coaches to the SEC.

Born March 9, 1961, in tiny Susanville, Calif., Leach grew up in even smaller Cody, Wyo. Raised as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he attended Brigham Young and earned a law degree from Pepperdine.

Leach didn’t play college football — rugby was his sport — but watching the innovative passing attack used by then-BYU coach LaVell Edwards at a time when most teams were still run-heavy piqued his interest in drawing up plays.

In 1987, he broke into college coaching at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, and he spent a year coaching football in Finland, but it was at Iowa Wesleyan where he found his muse. Head coach Hal Mumme had invented the Air Raid while coaching high school in Texas. At Iowa Wesleyan, with Leach as offensive coordinator, it began to take hold and fundamentally change the way football was played.

Leach followed Mumme to Valdosta State and then to the SEC at Kentucky, smashing passing records along the way. He spent one season as Oklahoma’s offensive coordinator in 1999 before getting his own program at Texas Tech.

From there, the Air Raid spread like wild and became the predominant way offense was run in the Big 12 and beyond.

Leach’s extensive coaching tree includes USC’s Riley, Dykes, Houston’s Dana Holgorsen and Kliff Kingsbury of the Arizona Cardinals.

Leach’s Mississippi State team finished 8-4 this regular season, including a 24-22 victory Thanksgiving night over Mississippi in the intense rivalry known as the Egg Bowl. It was his final game.

Defensive coordinator Zach Arnett was named the Bulldogs’ interim head coach, and interim athletic director Bracky Brett told ESPN that the team still will play in the ReliaQuest Bowl against Illinois on Jan. 2 in Leach’s honor.

“The players are 100% behind playing this bowl game and doing what Coach Leach would expect them to do,” Brett told ESPN. “We all know that’s what Coach Leach would want, and it’s what we should do.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.