Column: USC-UCLA crosstown rivalry makes overdue history with two Black starting QBs

Vince Evans remembers the crosstown rivalry for its unrivaled terror.

Before the 1976 game, Evans received a letter that contained the N-word with a warning: “If you go out there against UCLA, we’re going to blow your brains out.”

Such was the life of a Black quarterback.

“Imagine being a young kid playing under that kind of duress and pressure,” Evans remembered. “It was tough.”

Jimmy Jones remembers the crosstown rivalry for its unrivaled finality.

Despite directing the Trojans to an unbeaten season in 1969 and establishing several school passing records during his three years as a starter there, Jones was never given a shot in the NFL. He wasn’t drafted. He wasn’t signed as a free agent. He was never even offered a tryout. He spent a year working for Chrysler before spending his entire professional career playing in Canada.

Such was the life of a Black quarterback.

UCLA is out of the running for the College Football Playoff semifinals. Now the Bruins will eliminate rival USC from contention.

“We all know the weight USC carries, I thought I would at least get an opportunity in the NFL,” Jones said. “I was very upset.”

Fast forward to Saturday, when, after decades of relentlessness and lifetimes of heartache, a certain aspect of the crosstown rivalry will finally feature more unrivaled promise than pain.

When the USC and UCLA football teams have their 92nd meeting, it will be the first time both schools will be starting Black quarterbacks.

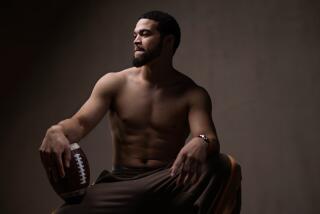

Caleb Williams is the powerful force who will guide USC. Dorian Thompson-Robinson is the inspirational leader who will direct UCLA.

And perhaps the most heartening part of this milestone is that most people won’t even notice.

Seven of the top 17 passers in the NFL are quarterbacks of color, including two MVP favorites — Jalen Hurts of Philadelphia Eagles and Patrick Mahomes of the Kansas City Chiefs.

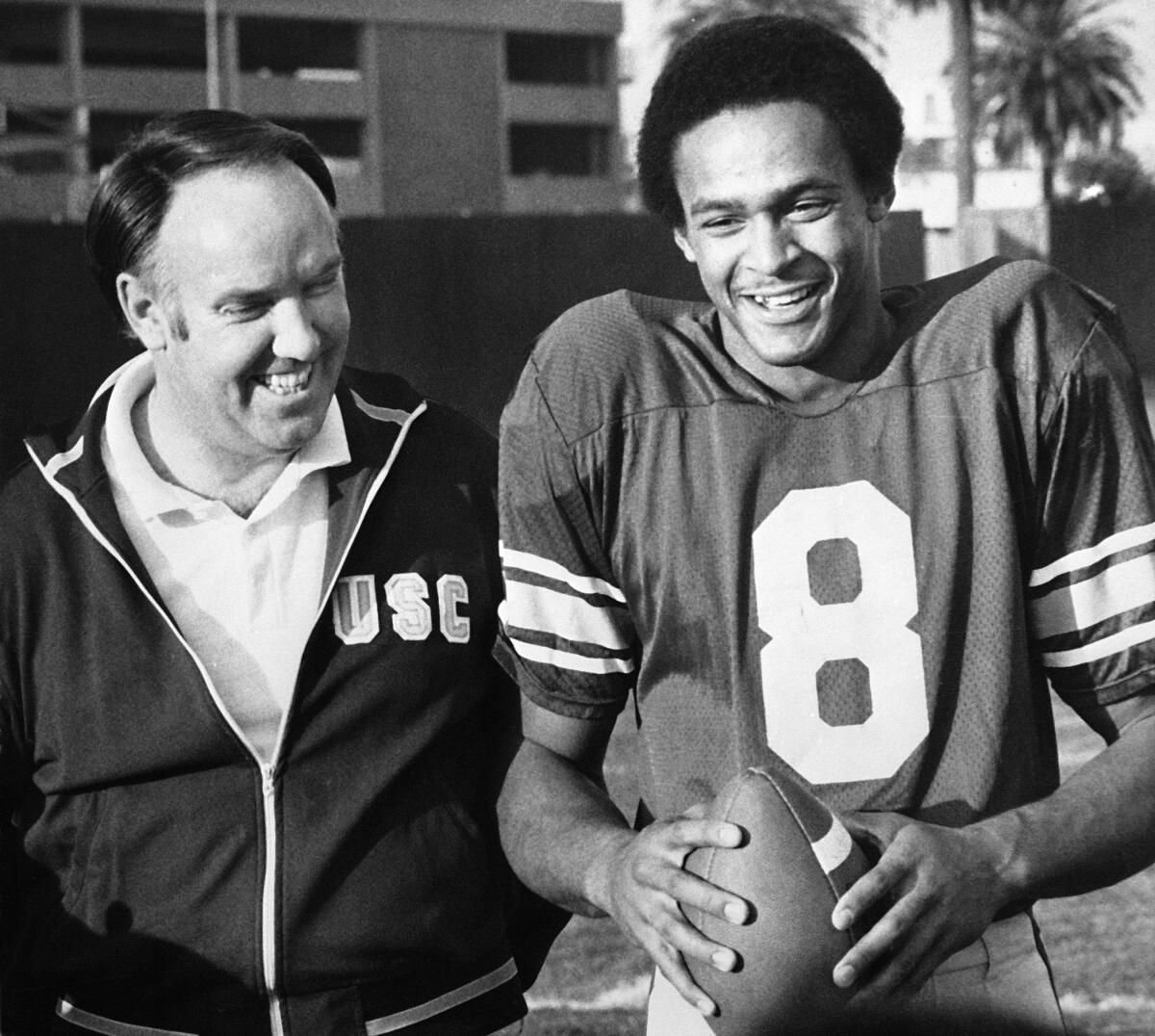

“I absolutely knew what I was doing. A tremendous number of people felt we did not need a Black quarterback and I was letting them know that I believed in him.”

— Former USC coach John Robinson on quarterback Vince Evans

Six of the top nine schools in the current College Football Playoff rankings are also led by Black quarterbacks.

“We’re in the age of the Black quarterback, everywhere you look there are superstar Black quarterbacks, and this game is emblematic of that change,” said Jason Reid, author of “Rise of the Black Quarterback: What It Means for America.”

As football has become big business, the hunger for success has confronted the ignorance of discrimination, and Black quarterbacks have finally been allowed to flourish in a world that once thought they lacked the traits necessary to lead a huddle or represent a franchise.

“The belief was always that Black players could not handle the rigors of the position, couldn’t read defenses … and that white players would not follow Black men because Black men were not leaders,” Reid said. “It finally changed for reasons of self-interest. When the money in this league became astronomical, these coaches and executives realized they had to win or get fired. They realized they needed a good quarterback who could no longer be judged by race. Green trumped Black.”

The USC-UCLA game appears a toss-up but NFL scouts have a definite opinion on whether Trojans’ Caleb Williams or Bruins’ Dorian Thompson-Robinson is a better NFL prospect.

Today the presence of a Black quarterback is so common that most interviewed for this column had no idea that Saturday’s quarterbacks will be making history.

“I didn’t know that, I think it’s awesome,” UCLA coach Chip Kelly told reporters. “I actually wish there wasn’t a talking point — it shouldn’t be a talking point. I think the two of those guys are unbelievable competitors and unbelievable quarterbacks.”

As a talking point, the issue of Black quarterbacks has indeed been increasingly muted. But for the two local teams, as with the rest of the national football landscape, change has been slow.

The first Black quarterback at USC was Willie Wood in 1957. At the time, the Trojans had been playing football for 69 years.

When Williams transferred here from Oklahoma this season, he became USC’s first impact Black starting quarterback since Reggie Perry in 1991, an amazing span of 31 years.

“We’re becoming numb to the Black quarterback, which is a good thing,” said Rodney Peete, who led the Trojans in the late 1980s. “But what’s happening Saturday, that’s a big deal.”

The first Black quarterback at UCLA was Kenny Washington in 1937. At the time, the Bruins had been playing football for 18 years.

When Brett Hundley starred from 2012 to 2014, he was the first impact Black quarterback at UCLA since Jackie Robinson in 1939, a span of nearly three-quarters of a century.

“The continuous rise of Black quarterbacks is absolutely a big deal,” said USC’s Jones. “Because you think back to the days when it was impossible to be one.”

Jones was the Trojans’ second Black quarterback when he started playing for them in 1969. He was recruited by John McKay, one of the era’s rare coaches who didn’t judge by color.

Jones was rated the top quarterback prospect in the nation at his Harrisburg, Pa., high school, but USC was one of the only schools to actually recruit him as a quarterback.

“Several people said you need to switch your position because they don’t have Black quarterbacks,” recalled Jones. “The perception that Blacks can’t play quarterback goes back to slavery. Why would you expect anybody you enslaved lead you in anything?”

Soon, McKay and Jones realized the size of their hurdles.

“I’ll never forget, one Christmas Eve, some guys in dark suits showed up on our porch,” recalled McKay’s son J.K. “They were from the FBI. Threats had been made against us because my dad was playing Jimmy Jones at quarterback.”

Jones said he was comforted by McKay’s strength and felt respected during a USC tenure that included a 22-8-3 record, a Rose Bowl win, and participation in the infamous 1970 victory against an all-white Alabama team.

“For USC to even be recruiting a Black quarterback at the time was big, very big, and I recognize John McKay for the courage he had,” Jones said. “I’m very grateful for my time there.”

He’s not so grateful for what happened next, a snubbing that led him to a championship career in the Canadian Football League.

“I never had a chance in the NFL, and whether it was 50% racial or 100% racial, I knew what time it was,” Jones said. “I’ll always be a little disappointed.”

“It’s…definitely a blessing as an African-American male to play this position, but to definitely have two in a big game playing both high-level football is definitely special.”

— UCLA quarterback Dorian Thompson-Robinson

The suffering was shared by Evans, whose entire USC career was played in an atmosphere that could best be described in a popular bumper sticker.

“Save USC Football. Shoot Vince Evans.”

Evans said he regularly received hate mail and was often peppered with boos. It got so bad, in his senior season in 1976, when he was leaving a game with an injury, new coach John Robinson purposely met him on the field and put his arm around him as they walked off. It was a scene reminiscent of Pee Wee Reese’s legendary embrace of Jackie Robinson. It was meant to send the same message.

“I could just feel the fans booing, he was embarrassed, and I absolutely knew what I was doing,” John Robinson remembered. “A tremendous number of people felt we did not need a Black quarterback and I was letting them know that I believed in him.”

USC’s path to the Pac-12 championship game is clear, but UCLA would need some help to play in the Dec. 2 game. Check out the title game scenarios.

Evans repaid that belief by leading the team to an 11-1 record and Rose Bowl victory in his final season. And that crosstown rivalry game with the threat upon his life? As extra security guards ringed the L.A. Coliseum field, Evans completed a USC victory with a 36-yard touchdown run that he still remembers today.

“Went down the left sideline,” Evans said. “Felt really good.”

A decade later, one might think that Peete had it substantially easier. Think again. Like his predecessors, he played for USC mostly because it was the only school that agreed to allow him to play quarterback even though he was a star quarterback in Overland Park, Kan. Among those places that wanted him only as a wide receiver were Penn State and Notre Dame.

“It made me mad,” Peete said. “Either those schools didn’t watch my high school tapes or they didn’t want a Black quarterback at their school. It was racial. I took it personally.”

Stanford actually promised Peete could play quarterback, but during his recruiting visit to Palo Alto, potential future teammates told a different story.

“I had 15 different Black players tell me, ‘They will not let you play quarterback,’” Peete remembered. “It was sad.”

After a successful college career that included two wins against Troy Aikman’s Bruins and a second-place finish in the 1988 Heisman Trophy voting, Peete’s dreams were once again crushed into reality.

In the NFL draft, he lasted until the sixth round, as nine white quarterbacks were taken ahead of him. That he played 15 NFL seasons proved the folly of the selections.

The USC-UCLA game is more than just a rivalry of the two Pac-12 L.A. universities. Many players on both teams were once teammates in high school.

“I learned the lesson that as a Black quarterback you’ve got to be twice as good, because if you’re even, they’re not going to pick you,” Peete said. “I think to a certain extent that’s still true.”

So, yeah, Saturday’s quarterback matchup matters, and the young stars know it.

“It’s…definitely a blessing as an African American male to play this position, but to definitely have two in a big game playing both high-level football is definitely special,” said Thompson-Robinson to reporters. “I’m definitely proud of him just as much as he’s probably proud of me.”

In his weekly interview session, Williams was equally awed.

“It’s awesome, to be honest,” he said. “That was one of the first things I was told, there hasn’t been a Black quarterback here in a really long time. It’s really cool, really awesome.”

Really cool. Really awesome. And long, long overdue.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.