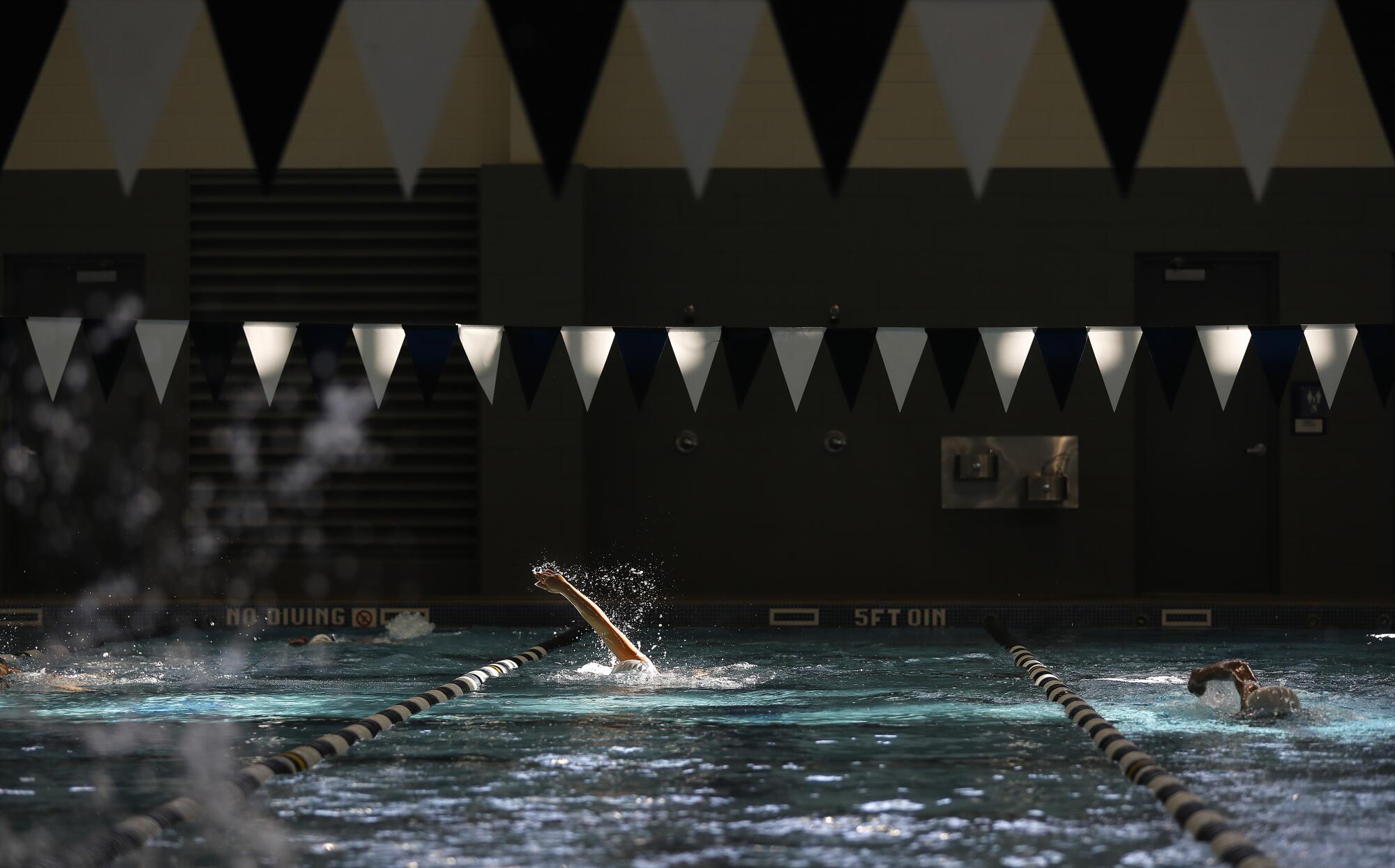

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. — Thick, hot chlorinated air immediately engulfs anyone who walks through the doors at Northern Arizona University’s Wall Aquatics Center. Between rhythmic slapping of arms hitting the pool’s surface and feet splashing water, swimmers gasp for breath, heeding the large sign hanging in front of the bleachers.

“Welcome to 7,000 feet — Catch your breath.”

Flagstaff is a popular training destination for endurance athletes hoping to capitalize on the benefits from high altitude. World-class runners, swimmers and triathletes from nearly 30 countries trained for the Tokyo Olympics in the city about 90 minutes south of the Grand Canyon.

As a professional Brazilian swim team took the pool in March, so did a group of teenagers from La Mirada.

The altitude training camp is La Mirada Armada’s secret weapon to compete with larger local clubs.

After completing the camp, Armada, a year-round swim club led by longtime coach Rick Shipherd, saw immediate results. At the team’s meet a week after returning to sea level, a 14-year-old girl set a personal record in the 1,500-meter freestyle after two weeks in Flagstaff. Two boys, who trained for only a week at altitude, enjoyed PRs in the 400-meter freestyle. Teammate Kayla Han broke the national record in the 400 individual medley for 13-year-old girls.

And Han didn’t even have a proper rest regimen going into the meet.

Armada’s star swimmer was just tuning up for her primary target: the U.S. International Team Trials. USA Swimming will use the meet beginning Tuesday in Greensboro, N.C., to select teams for the FINA World Championships and the Junior Pan Pacific Championships. Han, competing in the 400-meter, 800-meter and 1,500-meter freestyle and 400-meter individual medley, could become the youngest American swimmer to make a world championship team.

Han hoped to be perfectly primed to swim against Olympians such as Katie Ledecky and Katie Grimes with the direct benefits of training at altitude lasting about a month.

The body’s natural response to the thinner air — and less oxygen — of high altitude is to create more red blood cells. Athletes who spend three to four weeks at altitude can expect a roughly 4% to 5% increase in red blood cells, said Dan Bergland, a sport physiologist with Hypo2, a sport management company that organizes altitude training in Flagstaff. Bergland assists groups training at altitude by providing physiological testing that monitors red blood cell counts and VO2 max, a measurement of the amount of oxygen an athlete can use.

Bergland works in a room that looks more like a science lab than office.

Machines that spin blood samples line the counter and a stationary bike stands at center. There are so many signed swim caps and jerseys of teams that have partnered with Hypo2 for their altitude training camps that he has yet to hang them all up. Brazilian swimmers, Australian rugby teams and German triathletes are among those seeking the advantage of altitude training.

Athletes who enter with and maintain appropriate iron levels during the duration of their altitude training camps can expect roughly a 1% performance increase for a 4% red blood cell increase, Bergland said. It sounds negligible but consider that Germany’s Sarah Kohler finished seventh in the 800-meter freestyle in Tokyo. A 1% improvement on her time of 8 minutes 24.56 seconds would have put her in bronze medal position.

“The bottom line with all these Olympic teams, these people that are coaches and performance directors, their job is to get people on the podium,” Bergland said.

La Mirada Armada swim coach Rick Shipherd and his athletes stick to grueling, two-a-day routines with the goal of molding elite performers.

Armada’s Mia Carley vaulted onto the podium at the Fran Crippen Swim Meet of Champions less than a week after returning from Flagstaff, shaving 54.8 seconds off her seed time for the 1,500-meter freestyle to finish third. Her time of 17:53.64 was a personal best and the vast improvement was “unheard of” in the race, Shipherd said.

“I wouldn’t say [it was] easier,” Carley said, “but it was a lot more enjoyable than the last time I swam it. I was probably more prepared for it.”

The 14-year-old freshman at Fullerton Sunny Hills High already hopes to return to Armada’s next altitude camp. The club has been training in Flagstaff roughly every other year for the last 20 years. The team’s best swimmers typically go during even-numbered years to keep with the Olympic schedule, but the pandemic-delayed Tokyo Games led the club to Flagstaff during the 2021 season.

Han, who was 12 at the time, had no idea what to expect in the new environment. Last year, she had a shoulder injury that held her back during the team’s two-a-day practices that left athletes gasping for breath even during short workouts.

But in her first meet after training camp, she made the Olympic trials cut in the 400 individual medley. Her time of 4:50.70 was almost five seconds faster than two-time Olympic medalist Elizabeth Beisel’s national age group record for 11- to 12-year-olds. Han knew immediately she wanted to return to camp the following year.

This year, Han was Shipherd’s only repeat altitude swimmer. Armada is going through a youth movement and the altitude group featured prospects from 13 to 16 years old. Shipherd chauffeured them around Flagstaff in a rented minivan.

Shipherd wasn’t sure if he wanted to take such an inexperienced group to the grueling camp, but swimmers were requesting it. He decided it would be a good learning experience for everyone.

Setting the standard was the objective for this year’s camp and the reason why, when swimmers asked for easier sets, Shipherd sometimes denied the requests.

“Don’t be frail,” Shipherd told his swimmers. “This is why I brought everyone up here — to see if you can handle it.”

Altitude camp is a test in mental as well as physical strength. Han, one of the most remarkable examples of mental strength Shipherd has seen in his nearly four-decade coaching career, took it in stride. When the distance swimmers were assigned 50 100-meter freestyle sets, Han powered through the grueling 100-pool-length workout by nailing each 100-meters in the prescribed 1-minute-and-15-second interval.

The successful workout was one of Han’s early highlights of camp.

“[It’s] tough,” Han said. “That’s what we signed up for.”

Along with correcting stroke technique and assigning the next set, Shipherd encourages his swimmers to support one another in the pool. At altitude where swimmers feel like they’re working harder for slower times, maintaining the team’s supportive culture is essential.

Shipherd breaks up the monotony of training with off-day activities such as water-rafting trips and volleyball games. They keep score for head-to-head competitions, trivia and brainteasers where swimmers who finish drills first get to guess the missing letters of a phrase.

One team earned a point through a four-on-four volleyball game staged during an impromptu off day after their morning workout was canceled because of a pool malfunction. Their afternoon workout consisted of the volleyball game and an hour-long recovery swim focusing on stroke techniques.

Despite the easy day, the swimmers were sleepy during the next morning’s practice. They struggled to keep up with the intervals and their basic stroke techniques broke down.

“No failure swimming,” Shipherd barked as he implored them to “get their butts in gear.”

They responded, finishing the workout and earning prizes such as swim caps and T-shirts from the Brazilian team on the other side of the pool. The puzzle, fully solved on a nearby whiteboard, left the teenagers with a fitting message.

“Heart of a champion.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.