Commentary: For the Athletics, a home opener at the home they keep failing to escape

The team with the slogan “Rooted in Oakland” plays its home opener Monday night. Sometime soon, and perhaps as soon as this week, the Oakland Athletics figure to play before an audience counted in four figures.

The A’s did that 18 times last season, and we did not even start counting until June 29, when pandemic restrictions were lifted and the team could play to full capacity.

On Aug. 23, with the A’s 3½ games out of first place in the American League West, the team sold 4,140 tickets. On the same night, the A’s triple-A team in Las Vegas sold 6,213 tickets.

As soon as those crowd counts come in this season, the refrain will be inevitable: Oakland does not support the A’s! Move the team to Las Vegas!

Dave Roberts of the Dodgers, one of two Black managers in MLB, says the shortening of the draft has made it harder for Black players to reach the majors.

When you hear this — and you will hear this — bear in mind it is absolute nonsense.

I am from Montreal, and this is the same rubbish heard during the death spiral of the Expos. The formula appears the same: the owners trash the ballpark and say they need a new one; the owners get rid of your favorite players and say they cannot afford them; the fans wonder why they should pay to watch a revolving cast of players in a ballpark branded by the team as terrible; the low attendance becomes publicly mistaken as the illness rather than the symptom.

Since the end of last season, the team rooted in Oakland has cut costs by dumping star first baseman Matt Olson, star third baseman Matt Chapman, starting pitchers Chris Bassitt and Sean Manaea, and even manager Bob Melvin. The A’s slashed their player payroll by just about half — to $48 million, lowest in the majors, according to the Associated Press — and raised ticket prices.

Is this all a setup for owner John Fisher to throw his hands up at the end of this season and say, “No support, we’re outta here?”

Dave Kaval, the team president, likes to speak in long sentences, sometimes in paragraphs. His answer to my question about the legitimacy of the stadium pursuit was unusually short, and blunt.

“We wouldn’t be spending $2 million a month if we weren’t serious about staying in Oakland,” Kaval said.

Kaval has insisted repeatedly that the proposed waterfront ballpark, surrounded by a new and vibrant ballpark neighborhood and within walking distance from the heart of the city, is the cure for what ails the A’s.

“In a two-team market, with us competing against the Giants, we need a product that’s at the same level,” Kaval said. “That is what it is going to require for two teams to be successful in this marketplace.”

The Giants started this season with a $158-million payroll, and revenues about to soar as the team completes its new and vibrant ballpark neighborhood. Even if the A’s build that waterfront home, can they truly compete with the Giants in this marketplace?

Can the A’s really plan for a payroll in the top 10 in the major leagues?

“I think the revenue from a new waterfront ballpark in Oakland can support that,” Kaval said. “One hundred percent.”

The fans in Oakland can be excused for their skepticism. Kaval says the A’s would spend more if only they had a new ballpark, and of course that makes sense. But the “if only” part comes off to this ear as passive.

If only the A’s could have built that new ballpark in suburban Fremont — but they did not line up the community support. If only the A’s could have built that new ballpark in San Jose — but they did not get the Giants to yield their territorial rights, or get then-commissioner Bud Selig to twist the Giants’ arm. If only the A’s could have built that new ballpark in downtown Oakland — but they did not secure the support of the owner of the proposed site, or of the mayor.

Cincinnati Reds rookie Hunter Greene set a record with 39 fastballs hitting triple digits, but the Dodgers rallied for their fifth consecutive win.

This is not the fault of any one person, and it is not a lack of effort, or good faith. But the common element among all these proposals is the A’s. It is not unreasonable for a fan to believe the No. 1 reason why the A’s do not have a new ballpark after two decades of searching is, in fact, the A’s.

“This is a very challenging environment to build a new ballpark,” Kaval said. “It’s challenging to build anything in the Bay Area. There’s been a lot of reasons why we have not been able to be successful to date, but we are as close as we have ever been in the Bay Area.”

In 1992, after four elections in which the Giants asked taxpayers to fund a new ballpark and lost every time, owner Bob Lurie said he would sell the team to investors who would move the Giants to Florida. Major League Baseball intervened, allowing time for a San Francisco investment group to buy the Giants, keep them in town, and eventually put up a privately funded waterfront ballpark.

If Fisher wished to move the A’s to Las Vegas, it is considered unlikely Commissioner Rob Manfred would intervene, even if local investors offered to buy the team and build on the Coliseum site that Fisher refuses to consider. The A’s could have been playing in a new ballpark there years ago, and they could have developed the surrounding parking lot into a neighborhood of its own, just as the Angels are proposing in Anaheim.

But Fisher already is offering a privately funded ballpark in Oakland, and Manfred already has approved his exploration of opportunities in Las Vegas.

One of those opportunities?

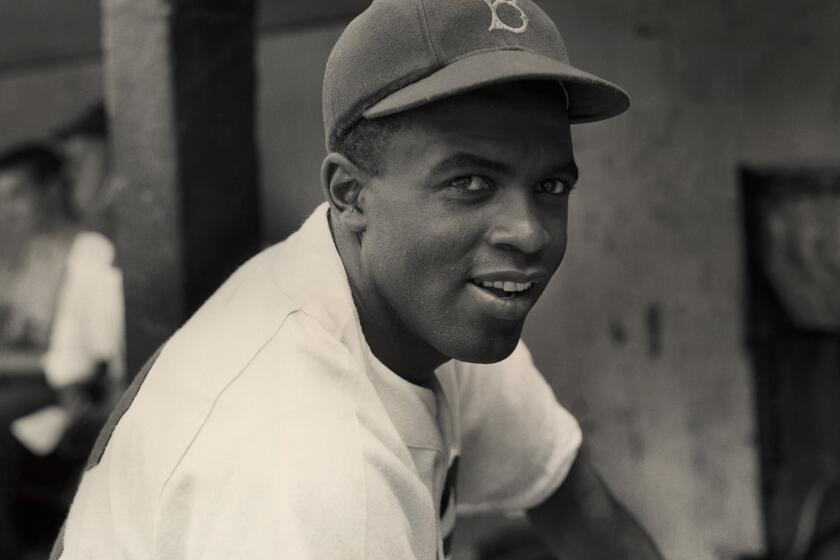

MLB celebrates Jackie Robinson Day on Friday, which is the 75th anniversary of the Dodgers legend breaking baseball’s color barrier. Here’s our coverage.

“We would be integrated in a new resort and casino,” Kaval said.

Nine months ago, Manfred said the Oakland stadium saga was “at the end.” He suggested the Oakland City Council needed to hurry up and approve the A’s ballpark plan or he might let the team look beyond Las Vegas. The council has yet to approve the plan, and Kaval said Oakland and Las Vegas remain the two cities under consideration.

The Cincinnati Reds have a new waterfront ballpark. In the 20 years they have played there, the Reds have made the playoffs four times and posted a winning record five times.

“We’re doing the best we can do with the resources that we have,” Reds president Phil Castellini said last week.

In those same 20 years, and in a ballpark lovingly branded by diehard fans as “baseball’s last dive bar,” the A’s have made the playoffs eight times and posted a winning record 11 times.

The A’s have Billy Beane running their baseball operation, teamed over the years with the likes of Paul DePodesta, Farhan Zaidi and David Forst. The Reds let the son of one of the owners run their baseball operation for five years.

In this 20th anniversary of the season that inspired “Moneyball” — a season in which the Angels won the World Series — the A’s still must sell fans on familiar executives instead of familiar players. Hope and faith in all markets, and Beane and Forst in theirs.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts did the right thing by removing Clayton Kershaw after he pitched seven perfect innings during his team’s 7-0 victory over the Minnesota Twins.

“We have David and Billy, who have done an incredible job,” Kaval said. “We are hopeful this period of time can lead us to a new era for A’s baseball, where there are additional resources on the player side.

“With the success we have had with such limited resources, it is exciting to think about what that could mean, and how that could lead to more world championships.”

It is indeed. More time debating whether Beane belongs in the Hall of Fame for his impact on the game, less time wondering whether Beane still will be running the A’s by the time they actually move into a new ballpark, in 2026 or 2027 or ...

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.