Was it hypocritical for the NFL to suspend Calvin Ridley for gambling? Maybe not.

The pushback was immediate and vitriolic, angry words bristling across social media and sports talk radio. Critics insisted that, in suspending Calvin Ridley for betting on football, the NFL was guilty of something even worse.

Hypocrisy.

How could officials discipline the star receiver so harshly for behavior that it promotes through partnerships with DraftKings and FanDuel?

“You should be allowed to bet on NFL games as a player,” Emmanuel Acho, a former pro linebacker turned television commentator, tweeted. “The rule should be you can only bet on your team to win.”

How could the league ban Ridley for all of next season — maybe longer — after handing down shorter suspensions for athletes convicted of violent crimes such as domestic abuse?

“A year?” former receiver Torrey Smith posted. “That math ain’t mathing.”

Many thought Aaron Rodgers might head to Denver, but he agrees to stay with the Packers, and Broncos trade for Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson.

Yet, for a billion-dollar sports organization mindful of its bottom line, the Ridley sanction might just represent what experts in law, marketing and ethics describe as a predictable — and reasonable — punishment.

“It might sound cynical, but we have to look at how these institutions are structured and what their purpose is,” said Shawn Klein, a philosophy lecturer at Arizona State and author of “The Sports Ethicist” blog. “The league exists to protect its game and any perception that players are involved in gambling is a direct threat to that.”

The NFL announced last week that Ridley bet on a series of games during a five-day period in late November 2021 while on mental health leave from his team, the Atlanta Falcons. The four-year veteran was reportedly in Florida when he used a legal gambling app on his cellphone. The wagers were flagged and reported to a compliance company employed by NFL.

A league investigation found no evidence that Ridley used insider information or that anyone else on the team was aware of his activity. Still, officials handed down an indefinite suspension through at least the conclusion of the 2022 season.

“Your actions put the integrity of the game at risk, threatened to damage public confidence in professional football and potentially undermined the reputations of your fellow players throughout the NFL,” Commissioner Roger Goodell wrote in a letter. “For decades, gambling on NFL games has been considered among the most significant violations of league policy warranting the most substantial sanction.”

“The league exists to protect its game and any perception that players are involved in gambling is a direct threat to that.”

— Shawn Klein, author of “The Sports Ethicist” blog

Ridley, who can petition for reinstatement in February 2023, cooperated with investigators.

“I bet 1500 total I don’t have a gambling problem,” he later tweeted. “I know I was wrong But I’m getting 1 year lol.”

From a legal standpoint, the NFL isn’t the only entity that prohibits its workers from participating in otherwise lawful activities.

Radio and television stations do not let employees enter their on-air contests. Corporate executives can be prosecuted for using insider information to buy and sell stocks.

“That the league supports sports gambling but disallows its players from gambling on sports is not necessarily contradictory,” said Marc Edelman, a law professor and director of sport ethics at Baruch College in New York.

Since the standard contract that all players sign, in accordance with the league’s collective bargaining agreement, prohibits betting on NFL games, Edelman said, “suspending a player is within the right of the league.”

“And I think a sports league would have a far easier time having the suspension of a player for betting upheld than they might have other suspensions upheld,” he said. “The misconduct cuts to the very essence of the job function.”

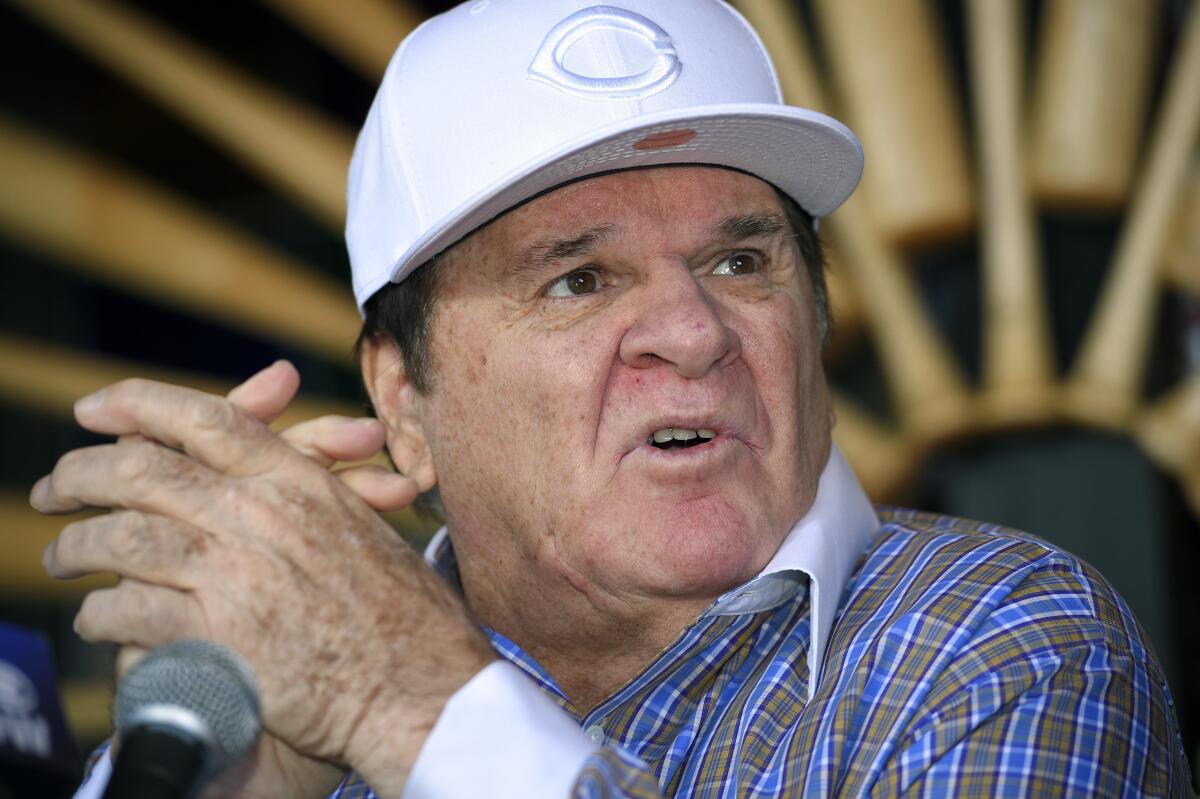

Consider the legacy of betting scandals in sport, a list that includes the Black Sox of 1919, college basketball point-shaving, Pete Rose’s banishment and the imprisonment of NBA referee Tim Donaghy.

It took a lengthy process — marked by time, social change and the allure of big money — to draw the NFL and other professional leagues into their newfound relationship with gambling. The shift began gradually with the popularization of March Madness office pools, rotisserie leagues and fantasy teams.

“I call them pizza gamblers,” said Jim Kahler, a former NBA executive who is now director of sports gambling education at Ohio University. “If you lose, you’ve lost pizza money, but that couple of dollars can enhance your enjoyment of the game.”

As wagering on sports became more acceptable, as it became legal in more states, leagues stopped fighting it.

In 2017, NFL owners overwhelmingly approved the Raiders’ move to Las Vegas, a decision that would have seemed inconceivable less than a decade earlier. Last year, the league signed a deal reportedly worth $1 billion to name Caesars Entertainment, DraftKings and FanDuel as official sports betting partners.

This emerging revenue stream came with obvious risks, so league officials established procedures to monitor betting patterns and watch for misconduct. Kahler views the Ridley suspension as proof that they acted responsibly.

“Now that [sports betting] is out and about, we’ve got to manage it right and stick to our guns with rules and regulations,” he said. “Let’s not kill the golden goose.”

“That the league supports sports gambling but disallows its players from gambling on sports is not necessarily contradictory.”

— Marc Edelman, a law professor and director of sport ethics at Baruch College

Debate over the length of Ridley’s punishment is not as easily settled by legal or marketing arguments. Critics point to incidents of domestic abuse involving players Adrian Peterson and Ezekiel Elliott that resulted in sanctions of six games each.

“The NFL just doesn’t value the impact of racist hiring practices, rape, domestic violence, DUIs, harassment and steroids on its business as much as a player betting on games,” quarterback Robert Griffin III tweeted.

As an ethicist, Klein returns to an objective view of what the league is, and is not.

Punishing criminal activity “isn’t what the NFL exists to do,” he said. “Not that the NFL shouldn’t do its part, but [crime] is more of something where society and the court system need to be the primary actors.”

No laws were broken in Ridley’s case, making league officials the only party in position to take action. But the incident now puts greater pressure on them to investigate allegations that fired coach Brian Flores has leveled against Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross.

In a racial discrimination lawsuit filed this year, Flores claims that while he was coaching the Dolphins during the 2019 season, Ross offered to pay him $100,000 for every lost game in hopes of gaining a favorable position in the subsequent draft.

The team issued a statement saying any “any implication that we acted in a manner inconsistent with the integrity of the game is incorrect.”

Failure by the NFL to aggressively pursue the accusation would bolster claims of hypocrisy, giving more ammunition to critics who, in terms of the Ridley sanction, probably won’t be mollified by talk of contractual stipulations or revenue streams.

Though Edelman views the suspension as legally sound, he does not count the last week as a victory for the league. Any time there is a whiff of gambling in the professional ranks, sports will suffer.

“Neither side comes out smelling like a rose,” the law professor said. “Nobody looks good here.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.