Before, when LeBron James preached, I would pass.

During his postgame news conferences, the Lakers star would answer all the basketball questions, then somebody would ask something about social justice and I would drift off.

My tape recorder was running, but my attention had shut down. I was there, but I wasn’t. I understood him, but I didn’t. I tried to relate, but I couldn’t.

George Floyd changed all that.

A year ago, Floyd’s murder by the knee of Minneapolis policeman Derek Chauvin resulted in a video that couldn’t be ignored and protests that couldn’t be avoided. The pandemic lockdown had removed all distractions and negated all excuses. Racial injustice was on our TV sets and in our streets, and we had nowhere to go and we couldn’t look away.

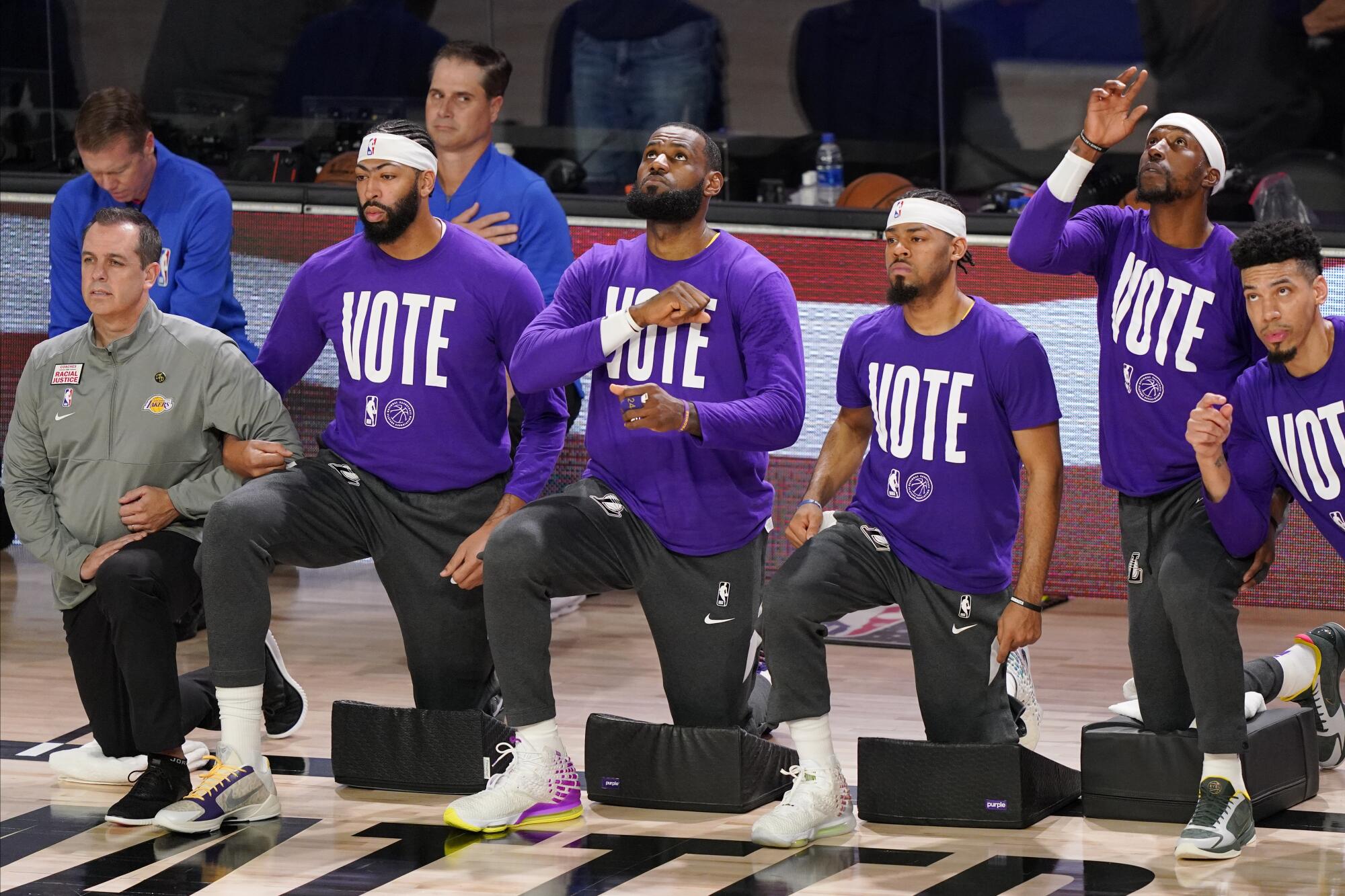

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, NBA players and coaches are speaking out once again about racial injustice and what must change.

While I have written about racial injustice throughout my 25 years as an L.A. Times sports columnist — campaigning for more Black head football coaches, detailing the Donald Sterling debacle, highlighting the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Freddie Gray and Eric Garner, marking the anniversary of the Rodney King riots — I was always able to quickly leave those stories to cover another game or profile another athlete. I could easily treat the injustice like a temporary condition that didn’t really affect me.

George Floyd made me slow down. George Floyd made me sit with it, absorb it, feel it. When the murder inspired sports stars to speak out as social leaders, I finally started listening — really listening.

For the first time, I heard their voices, attempted to understand their premises, and transcribed to the end of the tape.

“I know people get tired of hearing me say it, but we are scared as Black people in America,” James said last summer. “Black men, Black women, Black kids, we are terrified.”

People get tired of hearing him say that? I had never heard him say that. It’s because I wasn’t paying attention.

In a statement released Sunday, Clippers coach Doc Rivers said the response to George Floyd’s death has been ‘decades in the making.’

George Floyd made me pay attention, and the words were horrifying. James was a gifted millionaire and businessman living a blessed life, yet the fact that he was still in such pain was both repulsive and revealing.

“It’s just so sad … we’ve been hung, we’ve been shot,” said then-Clippers coach Doc Rivers last May. “It’s amazing to me why we keep loving this country, and the country does not love us back.”

The usually jovial Rivers fought back tears, and it startled me. I was surprised by such a public display of sorrow. This country did not love him back? Didn’t everybody love Doc?

George Floyd made me embarrassed at my naivete and ashamed of my ignorance.

During the Floyd protests, I wrote a column urging fans to view athletes as not only entertainers but also as real people dealing with real-world discrimination. In reading the words, I realized I needed to take my own advice.

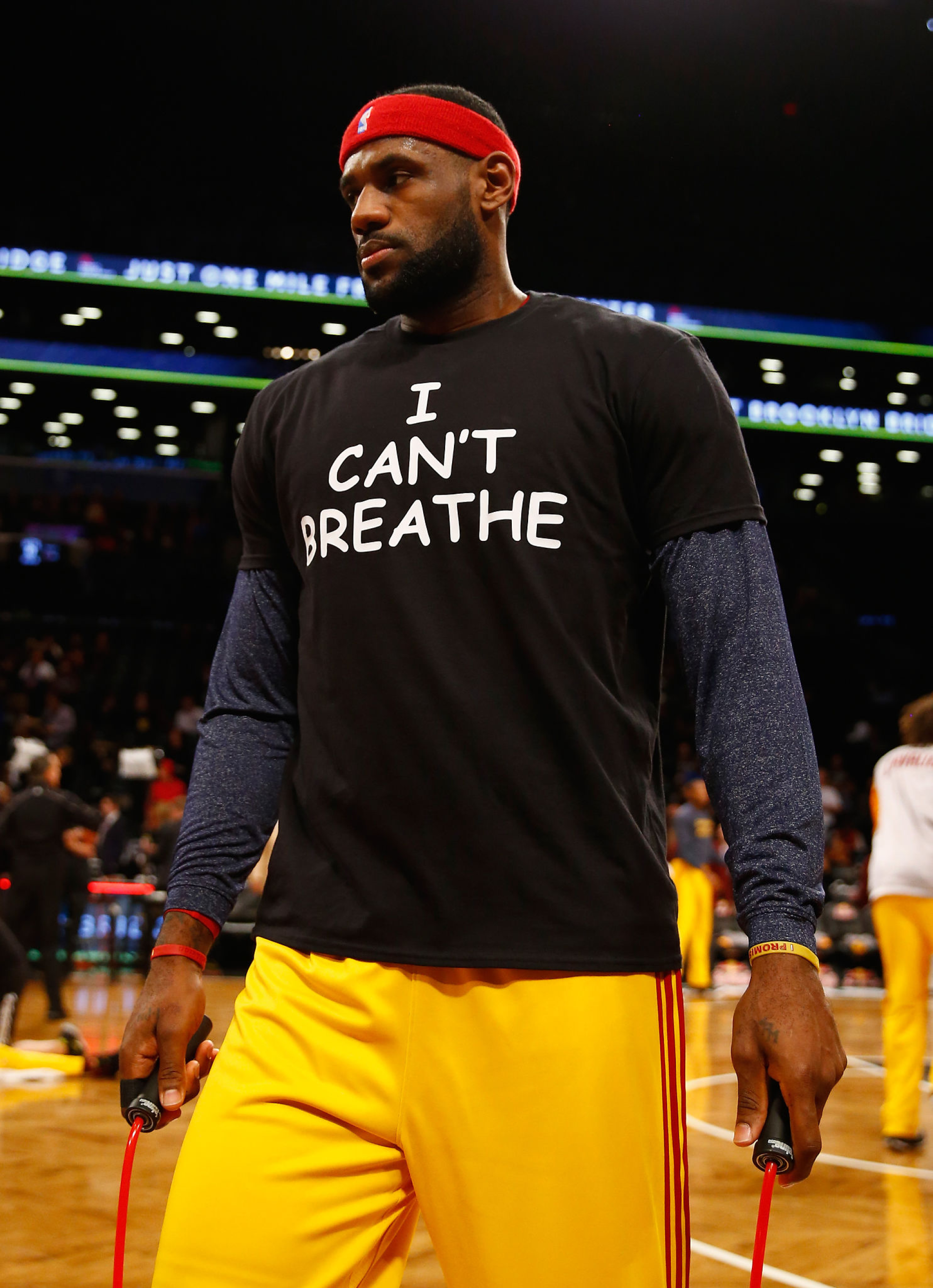

I have always supported athlete protests, but it always felt like they were taking place in a different world. It was fine that Colin Kaepernick took a knee, but I would never have reason to do the same. It was cool that NBA players wore “I Can’t Breathe” warmup shirts, but I never felt it necessary to buy one.

Doc Rivers encapsulates plight of black athletes: “When they’re wearing the uniform, they’re seen as an athlete. When they take it off, it’s a problem.”

I hated the despicable “shut up and dribble” mandate. I’ve always supported athletes speaking out on anything that is important in their lives. But my ears were rarely focused on the message and often only heard the dribble.

“It’s amazing to me why we keep loving this country, and the country does not love us back.”

— Former Clippers coach Doc Rivers

Shortly after Floyd’s murder, my youngest daughter returned home from participating in a protest march. She knew I had been pulled over for traffic infractions. She asked me to tell her my stories of unpleasant encounters with police.

I shrugged. I didn’t have any. I had always been treated with respect.

“What world are you living in?” she asked incredulously.

George Floyd made that world a lot bigger.

George Floyd made me realize that Kaepernick’s struggle was my struggle, and that if a Black man can’t breathe, we all can’t breathe.

George Floyd made me truly appreciate James as society’s most impactful athlete since Muhammad Ali, from his charter school to his voting rights group to his willingness to speak out at any time on all matters of social injustice.

“However you continue to create change for the better of all of us, I think it only makes us all better,” LeBron James said last fall during the NBA Finals. “It doesn’t matter what race you are. It doesn’t matter what color you are. … I think we’d all love to see better days and see more love than hate.”

It is the hope of Lakers star LeBron James that NBA players continue to speak out about social injustice and police brutality once the season is over.

George Floyd gave me new appreciation for what is arguably this country’s strongest group of professional athletes, the WNBA, where a group of players on the Atlanta Dream ran divisive owner Kelly Loeffler out of her Senate office and forced her to sell the team.

George Floyd made me realize the Dodgers had the mettle to end their 31-year drought and win their first World Series title since 1988 when they supported their only African American teammate, Mookie Betts, in sitting out a game in San Francisco.

“I talked to my teammates, told them how I felt, they were all by my side,” Betts said. “I couldn’t ask for better teammates than what I have here.”

It was the night Clayton Kershaw spoke for many of us when he said: “As a white player on this team … how can we show support? What is something we can do to help our Black brothers on this team?”

It was around this time that I phoned Broderick Turner, one of three Black writers on our L.A. Times sports staff at the time, and asked him something that had never come up in our countless conversations.

Mookie Betts showed his leadership and the Dodgers displayed their unity by getting the biggest win of the season in the fight against racism.

“Have you ever been hassled because of your color?”

Dumb question. Turner told an emotional story about a traffic stop. I had no idea. I had never cared to ask. Once again, I was embarrassed at my naivete and ashamed of my ignorance.

George Floyd opened my mind and popped my bubble and will hopefully lead me to write more columns like this one. But, make no mistake, these are not columns that should be praised. These are columns that should be expected. I deserve no applause. I can only hope for understanding.

When writing about social justice, I have always thought: I’m a middle-aged white guy. Who would want to listen to me? What credibility do I have in calling for equality in a world vastly different from my own?

Except in the year since the murder of George Floyd, it’s become clear: We’re all in the same world, the same place, and if one man has a knee on his neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds, we all do.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.