How Elgin Baylor handled the toughest job in sports: Working for Donald Sterling

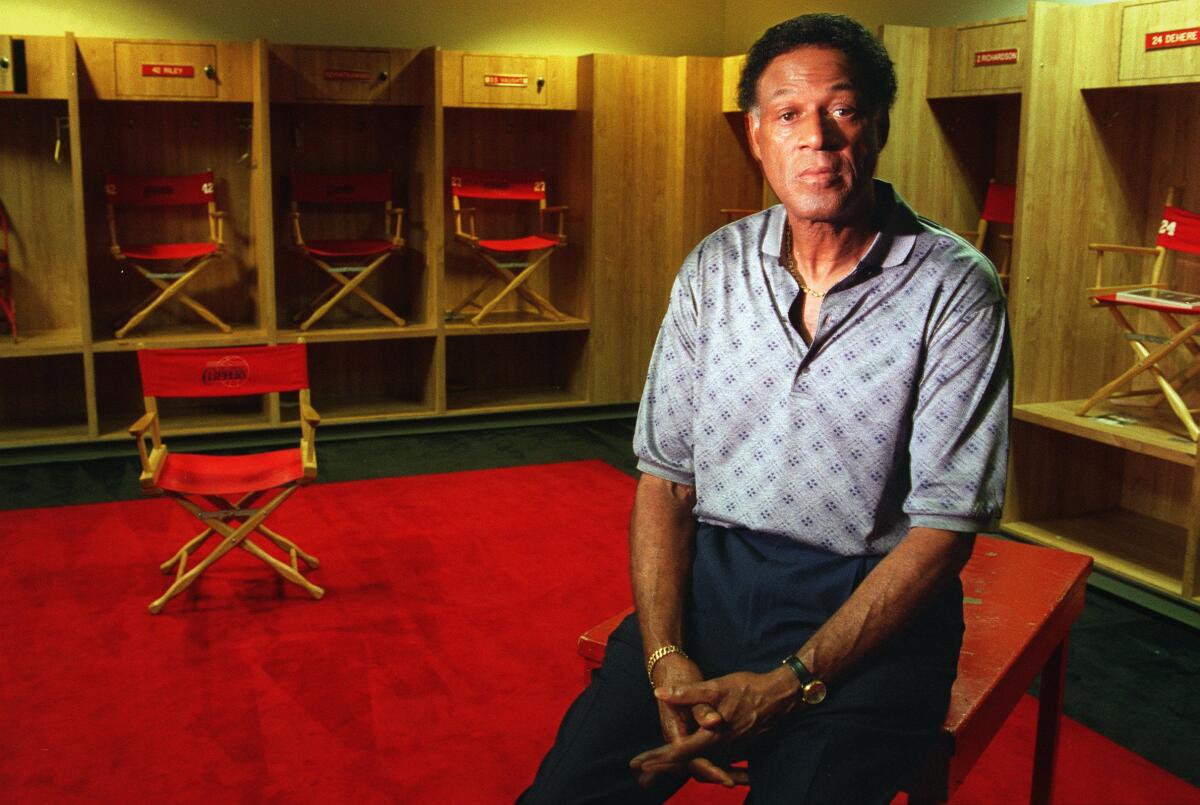

In the 1990s, Elgin Baylor’s Clippers co-workers sometimes referred to the general manager around the office as “legend.”

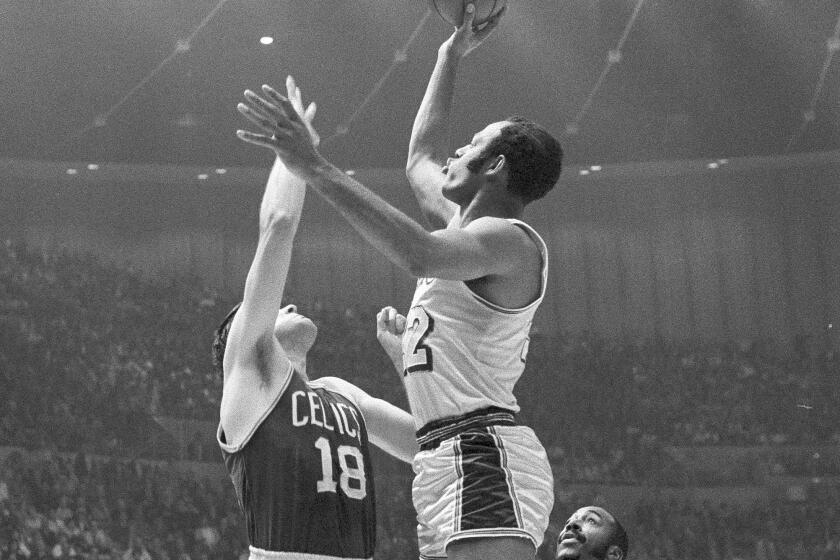

The nickname wasn’t hyperbole. During 14 seasons with the Lakers, the top pick in the 1958 draft “literally was Michael Jordan before Michael Jordan,” former Clippers coach Alvin Gentry said of how the 6-foot-5 forward seemed to be able to hang in the air. Still, in the years after Baylor joined the Clippers in 1986, the moniker could nonetheless feel incongruent, describing a Hall of Famer who rarely carried himself like one.

In the hallways, Baylor competed with colleagues in putting contests. He played cards on the plane with assistants. Over long offseason lunches, or sitting by someone’s desk, he’d unspool stories about an era when the league was so fledging, Lakers players washed their own uniforms. He discussed the January 1960 night when the Lakers’ plane crashed amid a snowstorm in an Iowa cornfield.

Then there was a drawn-out debate with Rob Raichlen, a communications staff member, about the best variety of apple. Days later, Raichlen found a sly reminder of Baylor’s stance waiting on his desktop — a Fuji.

“I love Fuji apples because of him, actually,” Raichlen said.

The good times belied the different side of the job, one remembered by friends and former colleagues as uniquely difficult.

Following Baylor’s death last month at 86, obituaries described both his Lakers brilliance as well as the end results of his 22-year run as the Clippers’ top basketball executive: four playoff appearances, three seasons of .500 or better, and 36% overall winning percentage, a run contrasted all the more by the success of the Lakers in that span, with five championships.

A look at the life and playing days of Lakers Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor, who would become an executive with the Clippers.

Such metrics, those people said, more accurately reflect the limitations Baylor endured under former team owner Donald Sterling’s management than Baylor’s job as an executive.

“I don’t know if he had the ability to do the job the way he wanted to do it,” said Gentry, who coached with the Clippers in three separate stints and now is an assistant in Sacramento. “I mean, when I say that, not his ability, but I mean the whole ownership thing and how he had to try to navigate that through everything. I think that was really difficult.

“I don’t think anybody had a tougher job in the league, really.”

A 2009 wrongful-termination suit filed by Baylor against Sterling, among others, painted the picture of a lead basketball executive granted unusual longevity yet only some of the authority normally afforded to his peers, such as the ability to negotiate with free agents.

A Los Angeles County Superior Court jury in 2011 rejected the claims that Sterling, the Clippers and then-team president Andy Roeser created a hostile workplace, yet former co-workers also described a general manager who no longer controlled the team’s drafts in his final seasons and also rarely was given latitude to negotiate with free agents.

“It wasn’t fair to Elgin. I’m prejudiced because I worked for the guy. There was one shining light in the place and it was Elgin Baylor.”

— Barry Hecker, former Clippers director of scouting and player personnel, on how Donald Sterling wouldn’t pay to retain talented players

“As guys played for the Clippers, we respected him, we idolized him so much, but you also got the feeling that he didn’t have quite the clout and gravitas around the organization that other people had,” said Marques Johnson, the former UCLA star who played for the Clippers from 1984-87. “And then you’ve got Jerry [West] running the Lakers. ... It was just a different dichotomy there. Just power and ability to make decisions. It was a tough time. A tough time in terms of [Baylor] gaining the appreciation for doing what he was doing at the time.”

Barry Hecker, who spent more than a decade with the Clippers as an assistant and also the director of scouting and player personnel, said that even though former top overall pick Michael Olowokandi never lived up to his top-pick billing, the franchise’s most promising teams under Baylor were built around a track record of solid draft choices. But those teams were unable to stay together, he said, because of Sterling’s unwillingness to spend to retain talented players.

“Elgin orchestrated a lot of that” success with playoff teams in 1992, 1993, 1997 and 2006, Hecker said. “It wasn’t fair to Elgin. I’m prejudiced because I worked for the guy. There was one shining light in the place and it was Elgin Baylor.”

Baylor got the job in 1986 at a time when few Black players followed playing careers into the executive suite. Then again, Sterling testified in 2011 that he didn’t know much about Baylor’s playing career at the time of his hiring, despite his 11 All-Star selections and standing as one of the game’s greatest players.

“You wanted to be that guy — in his image, his likeness and his demeanor,” said Julius Erving, a fellow member of the NBA’s 50th anniversary all-league team.

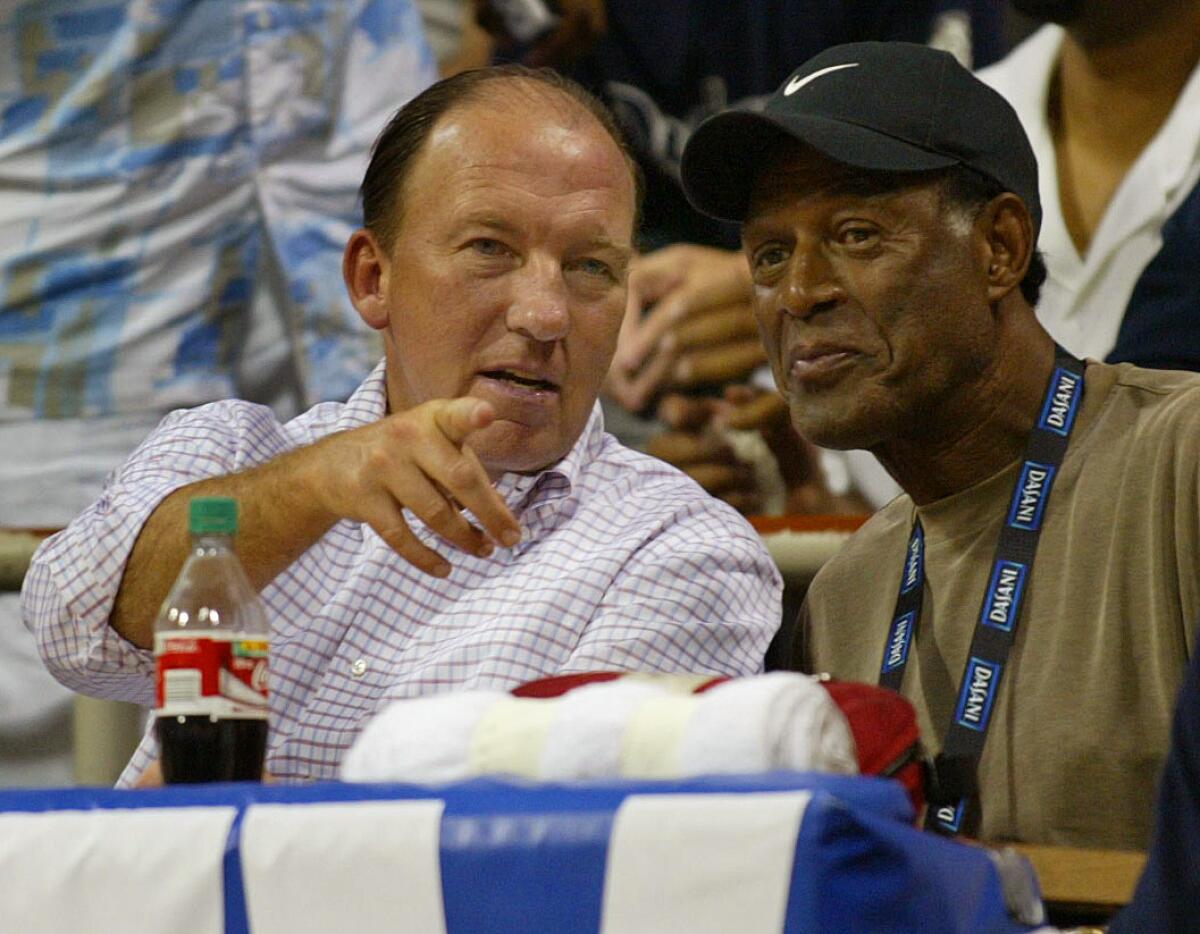

A lawyer, Sterling was more versed on Los Angeles real estate, a field in which he built his fortune while also running into trouble. In 2003 and 2009, Sterling settled federal lawsuits that alleged discrimination against African Americans, Latinos and others at buildings the lawyer and real estate mogul owned around Los Angeles. He settled the first case confidentially while also paying nearly $5 million of the plaintiffs’ attorney fees. He paid $2.765 million to settle the latter suit, but did not admit to any liability.

Baylor’s suit, filed five years before the NBA banished Sterling for life in 2014 for making racist statements, alleged that Sterling wanted a team of “‘poor Black boys from the South’ and a white head coach” and once told Danny Manning, the top overall pick in the 1988 draft, during contract negotiations that, “I’m offering a lot of money for a poor Black kid.” Steve Ballmer purchased the team in 2014.

Despite playing in a desirable market, the Clippers were rarely a draw for free agents.

“Through all of this he was very positive. That’s something that’s got to come from within because obviously it’s a really tough situation.”

— Alvin Gentry, former Clippers coach, on how Elgin Baylor approached his job

“Sterling repeatedly told Mr. Baylor that he was ‘giving these poor Black kids an opportunity to make a lot of money,’” the suit said. “But rather than offer them a fair market salary, Sterling’s approach was to try to put out negative, and even false information about the African American players, in an effort to reduce their value in the NBA marketplace.”

Following Sterling’s banishment, Baylor told CNN that Sterling often brought guests into the team’s locker room following games while saying, “‘Look at those beautiful Black bodies.’”

Baylor “did have the respect of the players and other front offices,” said Wayne Embry, the first Black general manager in the NBA, who held top executive roles in Cleveland and Toronto while Baylor was with the Clippers. “I think we all learned the circumstances he was working under. It wasn’t the most ideal situation.”

The suit described Baylor as underpaid compared to his peers — $350,000 annually for the final five years of his career, at a time when Clippers’ coach Mike Dunleavy was awarded a four-year, $22-million contract — and stripped of responsibilities usually associated with his title.

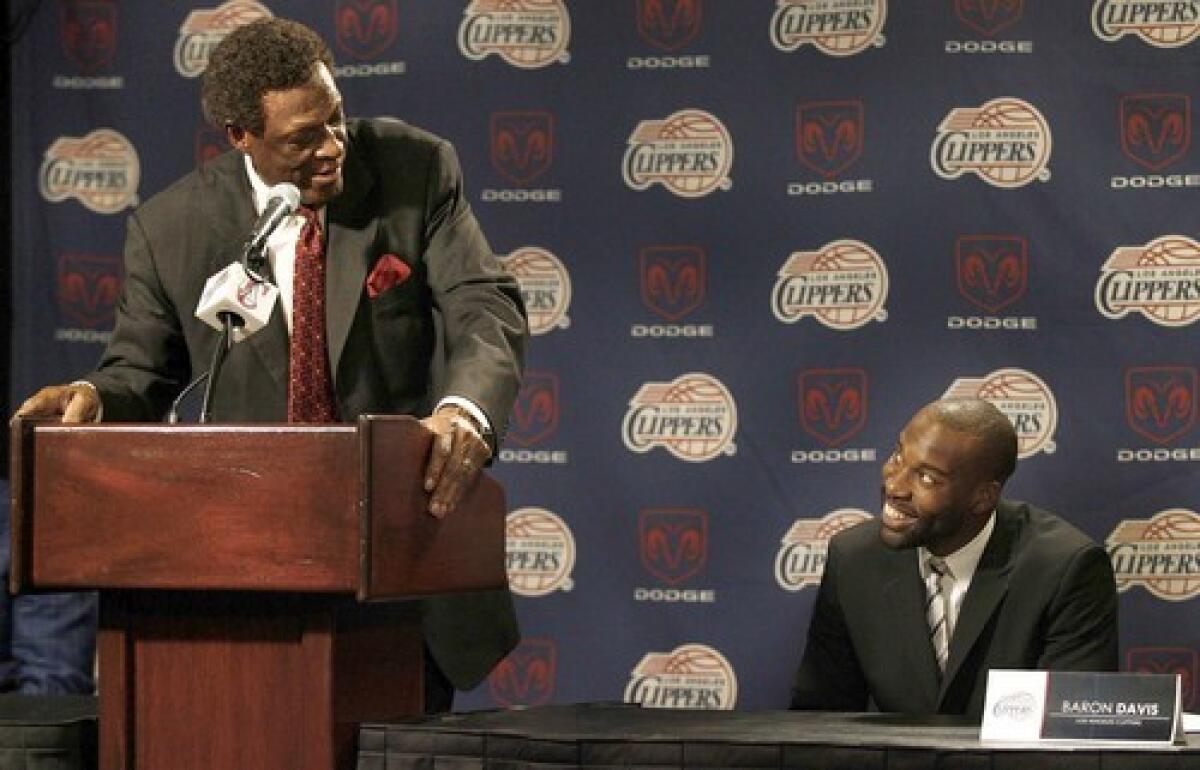

After Baylor was named the NBA’s executive of the year in 2006, when the Clippers came within one victory of the franchise’s first Western Conference finals appearance, the suit alleged that Baylor’s recommendations to re-sign players, including Elton Brand and Corey Maggette, were ignored and that he was eventually left to “get his news about the Clippers from public news reports.”

By 2007 and 2008, the team negotiated with players, but, the suit said, “left G.M. Baylor completely out of the process.” Baylor claimed he was forced out.

Colleagues said they never heard Baylor grouse about financial constraints that limited the team’s ability to build the roster.

“I don’t think he was comfortable saying much, especially given who he was working for, you know?” said Gail Goodrich, Baylor’s former Lakers teammate. “Sterling was a unique character in his own right. He meddled all the time in the operations. That’s not a secret. I think Elgin, in many ways, was reluctant to really step out beyond his comfort level.”

Baylor was described as an optimist who believed the team could reach prolonged success, becoming “at least respectable in the eyes of people around the basketball world,” as Johnson said. “That was kind of his mission.”

“Through all of this he was very positive,” Gentry said. “That’s something that’s got to come from within because obviously it’s a really tough situation.”

Still, when the news of Baylor’s death spread last month, it wasn’t his fraught relationship with Sterling, or the Clippers’ years of Sisyphean struggles, that lit up text threads among several of Raichlen’s former colleagues.

Raichlen remembered hearing Baylor walking the hallways humming a jaunty tune to himself after a big move. He remembered a feeling of awe realizing that “it’s arguably one of the best players who ever played the game and we’re just hanging out with him, literally all day.”

Occasionally, the executive would reveal the skills that earned him his nickname. During a shooting contest one day after practice, Raichlen was only a few shots from winning when Baylor dropped his ruse and began sinking shot after shot, winning in a runaway. After it was over, the GM kept shooting, for several minutes.

“I asked him, ‘What are you doing, Elgin?’” Raichlen said. “I’ll never forget this. He said, ‘I can’t stop until it sounds right.’”

Times staff writer Dan Woike contributed reporting.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.