Column: ‘This didn’t end well’: The year I assigned Leon Uris to cover the L.A. Super Bowl

As we watch Super Bowl LV, there will be an assumption that we will get giddy about Super Bowl LVI, where some team will play against Tom Brady. For the 2022 game, Brady will wear orthopedic shoes with Velcro and spikes. Nike will buy TV ads in senior-viewing time slots.

The truth is, in Los Angeles, we probably will be more fascinated than giddy. The Super Bowl will be returning to our backyard, but for many L.A. sports fans, the game triggers some cranky memories.

It does for me.

The Raiders and Rams left Los Angeles after the 1994 season. The Rams found Valhalla in St. Louis, near a giant arch that wasn’t a McDonald’s restaurant. The Raiders found theirs in beautiful downtown Oakland. No accounting for taste. Los Angeles never felt jilted. More amused and relieved. Bye-bye, Georgia Frontiere. See ya, Al Davis. Don’t let the door hit you in the ...

The NFL departure left us near barren in sports — only two NBA teams, two major league baseball teams, two NHL teams, the beginning of a pro soccer boom and some of the best college football and basketball in the country. Also, a beach and lots of sunshine. We muddled on, knowing that, with no local NFL team, there would be no Super Bowl.

The Super Bowl was a loss, especially in the newspaper business. I was running the sports staff of this paper starting in 1981, and while we knew that this game had become an obnoxious example of overblown excess, we pitched right in and did our part.

New Chargers coach Brandon Staley credits much of his success to the examples set by his father and mother, even as she eventually passed away from cancer.

At a Super Bowl in New Orleans, we were ready. At kickoff, there were 10 L.A. Times writers on press row, waiting for their story angle to emerge. When the lead got to three touchdowns and there was still time left in the first half, star columnist Jim Murray tapped me on the shoulder and said, “You can probably start sending people home at halftime.”

In ’87, when the Super Bowl was at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, I upped my game. It would be the Giants and the Broncos, and I decided to hire, for an advance story and game coverage, a nationally known writer. In retrospect, that was foolish. I already had Murray.

Assistant sports editor John Cherwa helped with the search. We almost had James Michener, but he was about to have surgery. Cherwa struck out with Stephen King and Robert Ludlum. He even tried Neil Simon, who might have woven the opposing Super Bowl coaches into an Odd Couple. Then I remembered I had read the novel “Trinity” by Leon Uris — one of his several books that sold millions of copies. We tracked him down and he said yes.

My rationale seemed sensible at the time. When Uris wrote, they made movies. When we wrote, they made fish wrappings.

Uris was a big Broncos fan. The deal was $5,000 for a preview story and $5,000 more for a gameday, deadline piece, plus expenses at a fancy Newport Beach hotel. His preview story was very good. Which brought us to gameday.

The Rose Bowl press box was cozy, and I had filled a large percentage of it with L.A. Times sports writers. The game went on, the Broncos lost — as they always did in the Super Bowl before John Elway figured it out — and I wandered the press box, making assignments and stressing deadline. In the prime seats, I had Uris between Murray and Jack Smith, also a legendary Times columnist, who was there to write for the casual sports fan.

As deadline approached, I saw that Smith already had headed home after filing his story and Murray was packing up, once again having written prose that would dazzle L.A. readers. Still seated in front of his laptop was Uris. Cherwa alerted me that there were only a few paragraphs on his screen. Uris saw me and started screaming, telling me that I had set him up, that I had unfairly seated him next to Murray and that he had looked at Murray’s screen and saw this marvelous prose, created in about 30 minutes, and that there was no way he could do that.

“Do you know how long it takes me to write one of my books?” he said. “Years and years. This deadline stuff is insane. I can’t do this.”

He sent what he had written to my screen and left. I never saw him again. We finished whatever angle he had begun and sent it to the office. It was the shortest, least compelling $5,000 story ever run in The L.A. Times.

The NFL was always a story, and so many connected to the Super Bowl.

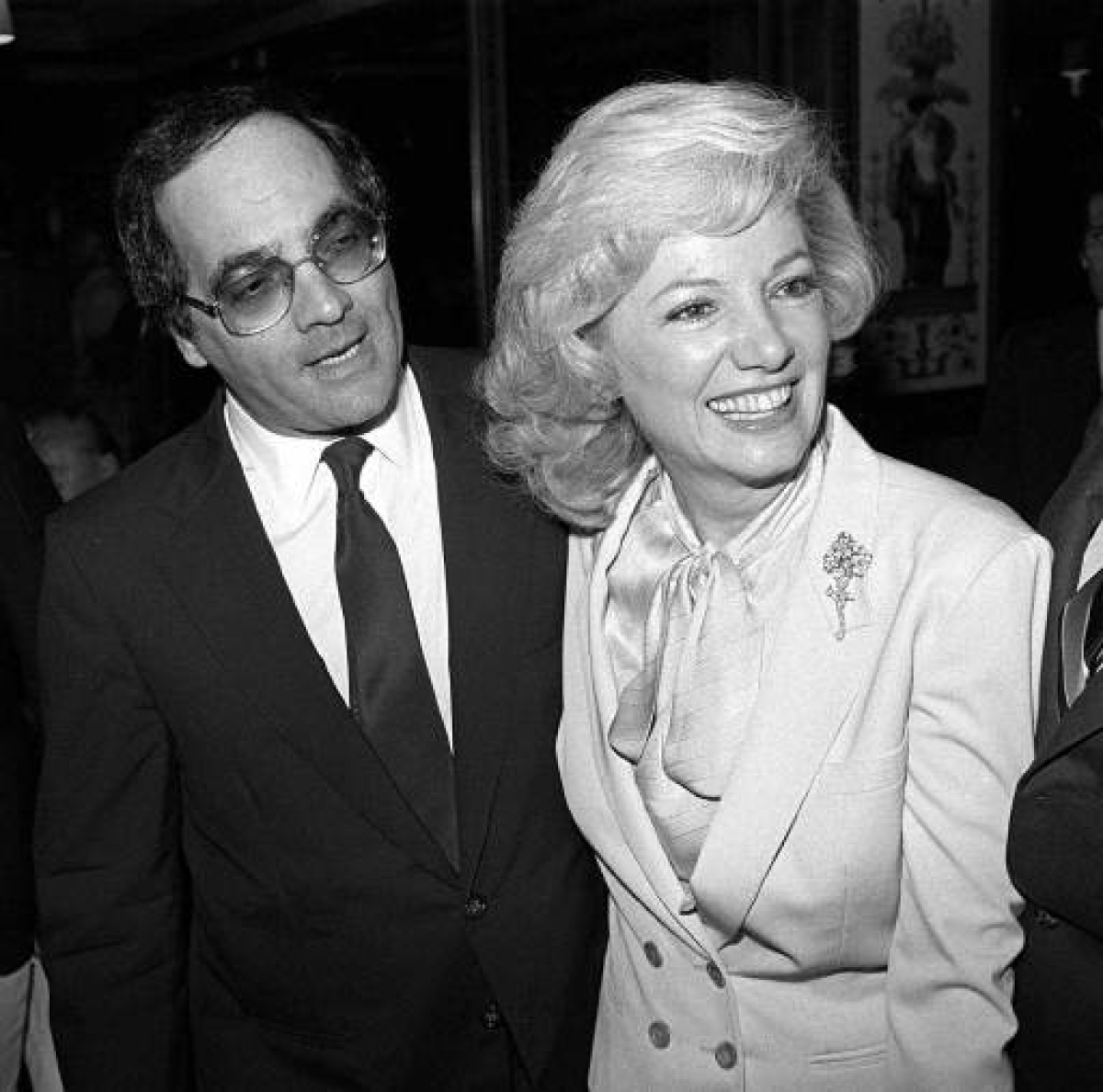

My arrival at the paper was the year after the Rams had played, and lost, to the Steelers in the 1980 Super Bowl in Pasadena. The team was owned by Frontiere, who had inherited it from her husband, Carroll Rosenbloom, who had died in a drowning accident. She had remarried Dominic Frontiere, a well-known Hollywood music composer and producer. There had been several ticket scandals in the wake of that Super Bowl and one allegedly involved Georgia and Dominic. The outcome of law enforcement investigations wasn’t clear, so I decided to have us do some digging. I assigned veteran reporter Ross Newhan, who eventually was inducted into the writers wing of Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

A couple of weeks after the assignment to Newhan, I was invited to a Rams game and The Times suite at Anaheim Stadium for a game. One of The Times people who invited me thought, since I was new to the paper, I should meet Georgia. They took me to her suite, where there were handshakes and cocktail party niceties until Dominic seemed to realize who I was. “Are you the guy who assigned that nasty investigative reporter to chase us around?” he snarled.

The place went quiet, and I was confused. Newhan was not a nasty reporter, just a good one. I had no idea to whom he had talked. I took a deep breath and said, yes, I had assigned a reporter and started to explain.

Frontiere was having none of it. He took a swing at me — not a good one but a swing nevertheless. I kind of danced out of the way and the swing missed. Manny Pacquiao would have been proud. I was hustled out and decided I would say nothing to anybody, although there had been several others in the suite.

The next day, local radio sports icon Jim Healy had it on the air and the guys on the sports copy desk started calling me “Rocky” and “Champ.” Five years later, Frontiere went to prison for nine months for selling the free tickets his wife had been given for the Super Bowl and not paying taxes on the profits. Soon after he got out of prison, Georgia divorced him.

Once the Rams and Raiders left in ’94, the ongoing, almost daily, story was about getting a team back in L.A.

I took a walk one night with Peter O’Malley, Dodgers owner, who had a plan to build a football venue next to Dodgers Stadium in Chavez Ravine and was talking to NFL officials. “Look at this view,” O’Malley said. Soon after that, Mayor Richard Riordan sent O’Malley a letter, asking him to back off so downtown interests could push the Coliseum as L.A.’s main site. O’Malley was crushed and kept the letter from Riordan on his desk for years.

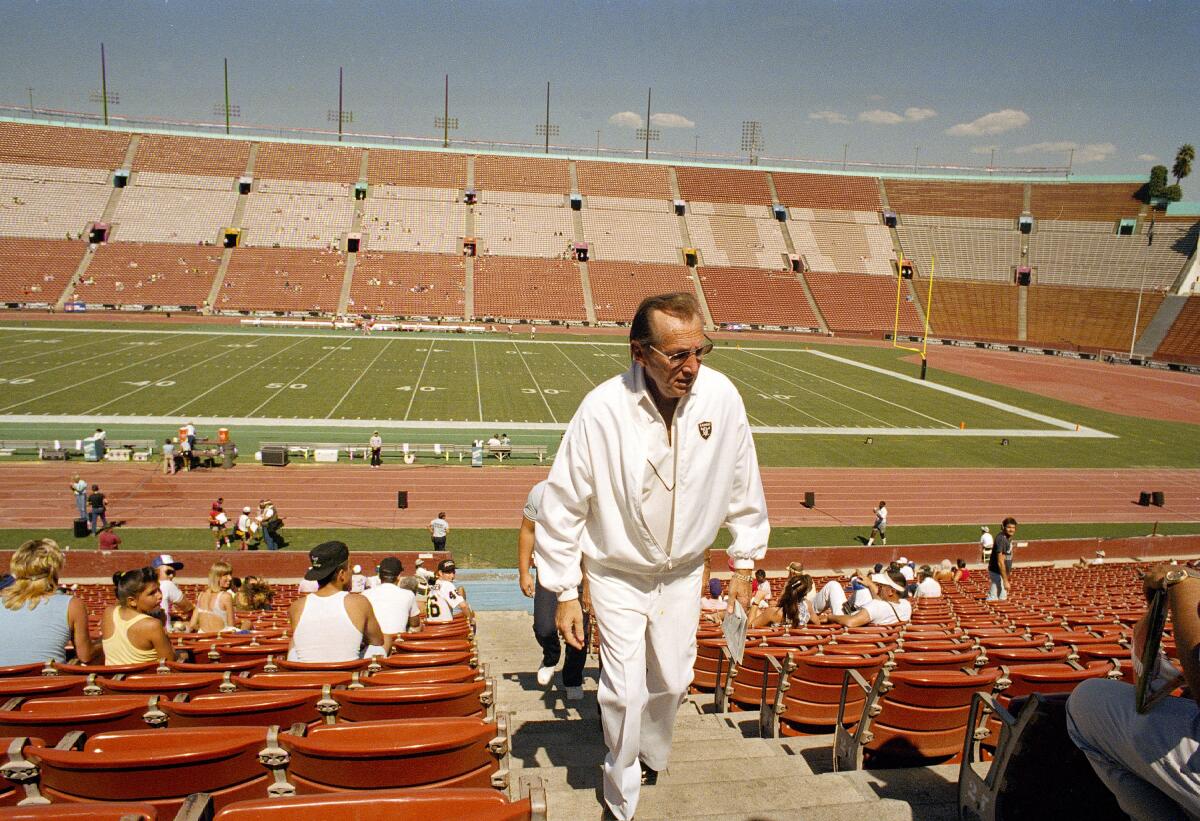

Well before that, Al Davis was sick of playing in the crumbling Coliseum. The sprucing up for the ’84 Olympics was un-sprucing. Davis took a look around and saw a gravel pit he liked in a little city along the 210 freeway. He somehow got the city fathers of Irwindale to write him a check for $10 million so they’d be first in line for the Raiders to build. The city had banners and T-shirts and celebrations with cheerleaders. Davis never built, and the check never came back to Irwindale.

Years later, Davis appeared to have an agreement to build a stadium at Hollywood Park. His partner in the deal, Hollywood Park Chairman R.D. Hubbard, thought he had a done deal and called a news conference luncheon. But the NFL had told Davis they would go along only if two teams played in his new facility. Davis didn’t like sharing. There were banners and a place ready for celebration, with silverware and napkins on the table. But Hubbard was left alone at the altar.

The city kept pushing hard for the Coliseum. Steve Soboroff, longtime city activist, and Fred Rosen, president of Ticketmaster — as well as several politicians, including Mark Ridley-Thomas — led that early charge. Hollywood talent agent Michael Ovitz, who founded Creative Artists Agency and was once president of the Walt Disney Co., had a group that wanted to put a stadium on some vacant land along the 405 freeway in Carson.

In the late 1990s, The NFL was talking expansion and each group wanted the endorsement of The Times. Each scheduled a luncheon and came to The Times’ corporate dining room, where enough expensive art hung on the walls to purchase the NFL team ourselves.

Ovitz’s group came first, and arrived early. When I showed up, along with a handful of other Times editors and corporate executives, Ovitz had arranged all the seating and I was directed to a place right next to Tom Cruise, who was part of the investment group and was wearing a Notre Dame cap, the school I attended. Tom and I chatted like old friends. Then, The Times endorsed the other group. Tom stopped calling. From the start, it had been a mission impossible.

In 1999, the NFL announced that Los Angeles would get the expansion team, but nobody from L.A. seemed eager to write a check. Eventually, Ovitz, who had joined the Coliseum group, offered $540 million from his group for the expansion fee. A Texas oilman named Bob McNair had shown an interest, but always had been shuffled aside by the NFL as it waited for Los Angeles. When the NFL got Ovitz’s offer, it called McNair to see if he was still interested. He wrote a check for $700 million and the Houston Texans were born.

Los Angeles kept trying. After the expansion plan failed, the only option was to entice an existing team to move. Denver oilman Phil Anschutz was led into the fray by one of his top executives, Tim Leiweke. Anschutz (Anschutz Entertainment group, AEG) built much of what is now LA Live and the plan was to use that as a commercial backdrop for an NFL team’s new stadium, to be built on the site of part of the convention center. Years of deal-haggling took place and went nowhere. Leiweke was eventually separated from AEG and Anschutz lost interest.

One of his early business partners, a wealthy real estate executive named Ed Roski, kept trying, presenting plans for a stadium near the 57 and 60 freeways. Roski had an eager, crafty spokesman, John Semcken, who kept assuring that the Roski deal would be done. Semcken, a former Top Gun pilot and advisor on the movie of the same name that starred Cruise, was a tough guy to doubt. He could convince an orange it was a lemon. But the NFL was one tough banana and Roski’s deal never happened.

It was left to Stan Kroenke, who reportedly is worth $10 billion and was willing to spend half of that on a stadium at the same Hollywood Park site that Hubbard and Davis once coveted.

All that ruckus for all those years, and it was simple. Kroenke wrote a check. He spent his money. It took a guy from elsewhere to star in Hollywood.

Feb. 6, 2022. The Super Bowl will come home. The first one was in the Coliseum in 1967, nice but already 44 years old. This one will be in shiny new SoFi Stadium, a lap of luxury.

If only Leon Uris were around to write about it.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.