Something was wrong with Hayley Hodson. She had come to Stanford as the country’s top volleyball recruit, an Olympic hopeful whose high school mornings in Newport Beach were self-scheduled down to the minute, the better to start classes early so she could lift weights before afternoon practice.

6:00 a.m. — Wake up 6:03 a.m. — Brush teeth 6:07 a.m. — Drink coffee, eat Greek yogurt 6:13 a.m. — Get backpack

Now Hodson could barely get out of bed. It was late September 2016, and the Cardinal were in Washington state. Hodson, a sophomore captain, was a returning All-American and National Freshman of the Year.

She also was in pain. Her shins had been aching for months. Her swollen left foot was in a walking boot.

Those were the visible problems.

Since late 2015, Hodson had suffered migraines and insomnia, anxiety and exhaustion. A diligent student who learned calculus through online self-study, she couldn’t concentrate in class. She needed reminders to eat.

Earlier in the month, Hodson had been diagnosed with clinical depression. She took medication but didn’t feel better. Prior to the Washington trip, Hodson called her parents — Jimmy, an actor who is the voice of In-N-Out Burger, and Sonya, a television producer who worked for CBS Sports and on “Touched by an Angel.”

Kevin Ellison was known for hard hits while playing for USC and the Chargers. Did that lead to increasingly bizarre behavior before his death?

I won’t be playing, she said. But I need you here anyway.

Sonya made the trip with her sister-in-law, Char Hodgson. The team was staying at a hotel in Spokane. Around 4 p.m., Sonya called her daughter’s room.

There’s a steakhouse downstairs. Why don’t you come meet us?

Mom, I can’t imagine getting out of bed.

Hodson hung up. Moments later, Sonya called back.

You need to eat. I’ll come get you.

Hodson’s mood was dark. Her eyes watered. She kept resting her head on the restaurant table. She “talked in circles,” Sonya says. “Nothing made sense.”

Under the table, Char grabbed Sonya’s hand. Sonya was afraid. She knew something was very wrong.

Only later would she learn Hodson already had played her last match.

Within 10 months, her daughter retired from the sport with a diagnosis of post-concussion syndrome, the result of what the family would claim were brain injuries suffered after being hit in the head with volleyballs near the end of her freshman season. Hodson filed a lawsuit in 2018 against Stanford and the National Collegiate Athletic Assn. for failing to provide proper medical care for those injuries, allegations the school and the NCAA deny.

‘A dream athlete’

Ever since her family attended the 2002 Salt Lake City Games when she was 5, Hodson wanted to be an Olympian. Her youth softball team won a national championship when she was 8; the next year, she quit after the sport was dropped from the Summer Games.

“I was a go-for-the-gold-type person,” she says.

Hodson turned to volleyball. At first, she hated it. The net was too high. The ball jammed her fingers. But Hodson was tall, standing 6 feet in eighth grade.

She also was determined. At 12, Hodson attended a tryout in San Jose for USA Volleyball’s high-performance youth program and caught the eye of then-program director Denise Sheldon.

“Hayley was at the top of my depth chart” from that moment forward, says Sheldon, who in 2016 managed the women’s national team at the Rio Games. “What stood out to me with her, year after year, is that she would do whatever it takes to make our [youth] national teams.”

As a freshman, Hodson led Corona del Mar High in scoring as the school reached the 2011 Southern Section finals; as a junior, she took a leave of absence from school to play for the gold medal-winning U.S. squad in the U23 world championships in Mexico, finishing as the team’s third-leading scorer.

At the invitation of women’s national team coach Karch Kiraly, Hodson became just the third high school player to train with America’s senior squad, spending two months competing against professional players she mostly had seen on television.

“If you gave her a responsibility, there was absolutely no question she would make sure it got taken care of. She was the epitome of a kid with persistence and mental strength.”

— Denise Sheldon, former program director for USA Volleyball’s high-performance youth program

“Hayley absolutely had the potential to play on the Olympic team,” says Holly McPeak, a three-time Olympian and Hodson’s high school beach volleyball coach. “She had all the skills. She was coachable and hardworking. In my eyes, she was a dream athlete.”

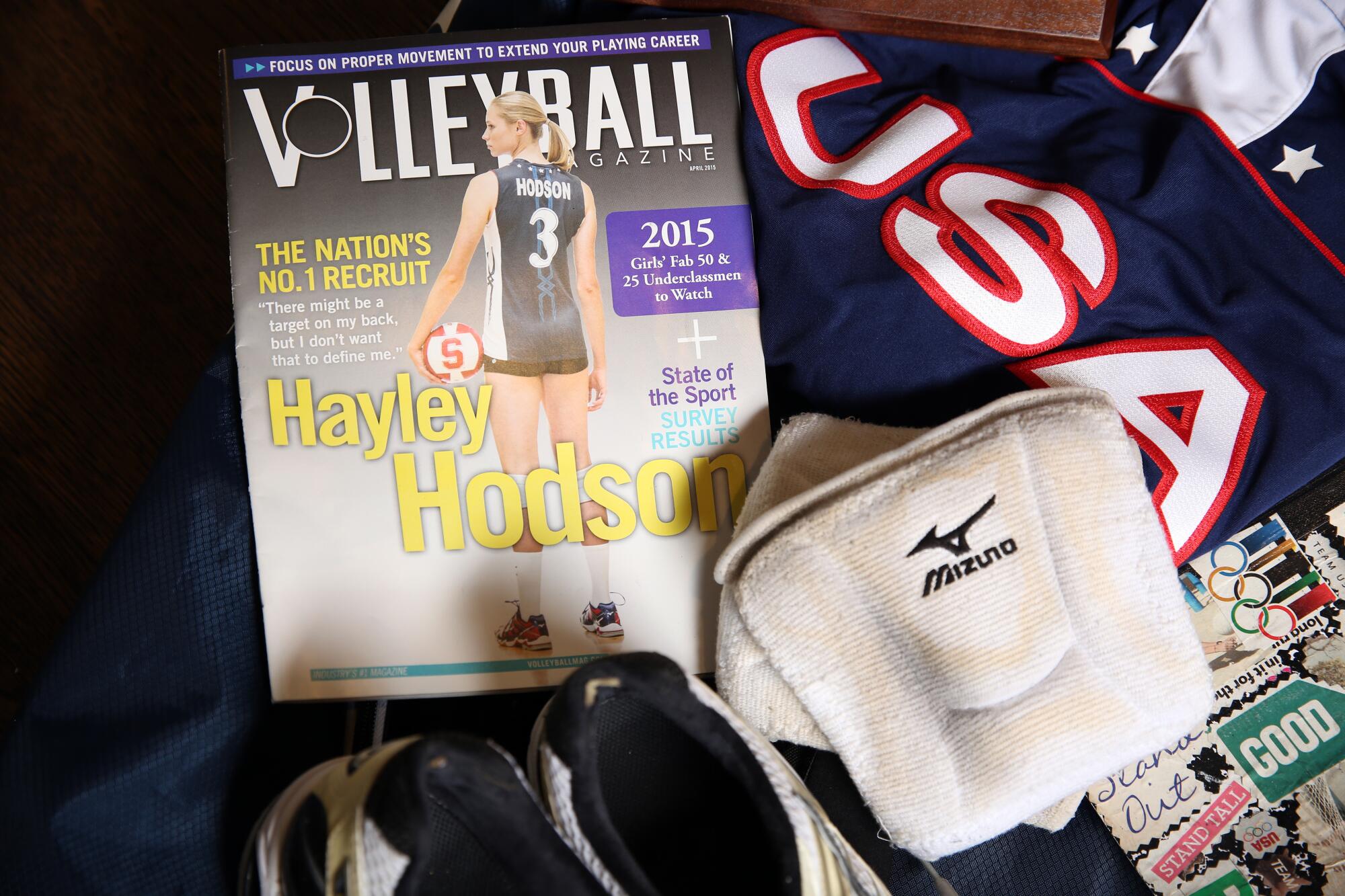

In April 2015, Volleyball Magazine featured Hodson on its cover as the nation’s No. 1 college volleyball recruit.

And Hodson had a plan: Graduate college in less than four years. Train with Team USA. Play in the 2020 Tokyo Games. Play pro volleyball overseas. Return for law school, spring-boarding from sports into broadcasting or legal work.

“Hayley never seemed to go through the chaos teenagers go through,” Sheldon says. “If you gave her a responsibility, there was absolutely no question she would make sure it got taken care of. She was the epitome of a kid with persistence and mental strength.”

When Hodson arrived at Stanford in August 2015, Jimmy Hodson says, then-Cardinal coach John Dunning told him that she was the most well-prepared freshman he had ever seen. She earned All-Pac-12 honors, leading the team in kills, points and service aces.

Hodson’s days were demanding: four hours of morning classes. Get to Maples Pavilion by 2 p.m. to get taped and warm up for practice. Practice from 4 to 8 p.m. Lift weights until 9. Homework and film study until after midnight.

Yet, Sonya says, “all I got every day from Hayley was, ‘Mom, this place is great. I’m at home here. I love it.’”

Two hits

Two hits, the family says, changed everything.

The first happened Nov. 9, 2015. During a Stanford practice, Hodson says, Dunning had her and teammate Madi Bugg perform the “courage” drill.

In a 2012 YouTube video, Dunning demonstrates the drill, which he says improves “reaction time and focus.” Players stand 10 feet from the net; on the other side, a coach atop a stool slaps sharply angled, medium-speed shots toward the players, who dig the ball with their arms while keeping their heads out of harm’s way.

“You need to be careful with this,” Dunning says in the video. “We call it the ‘courage’ drill appropriately. If I were you and going to do this — well, I don’t know if I would do it at all.”

Hodson’s lawsuit says the drill was “dangerous,” and she said her teammates hit full-speed shots.

A ball struck Hodson on the right side of her head. Her Stanford athletic medical records describe what happened next: A team athletic trainer had her take a sideline neurocognitive test used to evaluate injured athletes for concussions. Hodson had trouble seeing out of her right eye. There was worry she had suffered a detached retina.

A teammate drove Hodson to the campus hospital, where she was diagnosed with a “likely closed head injury/maybe minor concussion.” The next day, the medical records show, a Stanford team doctor diagnosed a “mild concussion.”

“She very much wasn’t herself, but we never even thought about the concussion. Once a kid gets cleared, nobody ever mentions it again.”

— Sonya Hodson on her daughter’s health

According to a 2015 study published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine, women’s volleyball has the ninth-highest concussion rate among 25 NCAA sports. Most athletes who suffer a single concussion — with rest and a gradual return to activity — experience no lasting ill effects.

However, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a number of medical studies, athletes who suffer a second concussion while recovering from a previous one face a greater risk of prolonged or permanent symptoms, including chronic headaches, mood and behavioral changes, and cognitive impairment.

Suffering multiple concussions also has been linked to increased risk later in life of depression and cognitive impairment, while exposure to repetitive brain trauma — including sub-concussive hits to the head that don’t cause obvious symptoms — is associated with the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease found in the brains of several high-profile athletes following their deaths.

In high school, Hodson says, she was diagnosed with her first concussion following volleyball hits to the head. Afterward, she suffered from insomnia and distorted vision, an account confirmed by Team USA doctor Chris Koutures, who treated her. She didn’t play for more than a month; when she experienced vertigo and a tingling sensation in her first practice back, she was sidelined again until her symptoms subsided.

Ideally, Koutures says, athletes should not return to play until they are symptom-free. But in the middle of a season, he says, all of that can be challenging.

“There’s pressure for athletes to get back,” Koutures says. “It can be self-imposed, ‘I don’t want to miss the big game, so I will tell people what they want to hear.’ Or it can be pressure from the team or coach.”

Hodson was concussed on a Monday night. On Tuesday, Stanford’s medical records indicate she told a team doctor that she was suffering from headaches and “feeling in a fog.” She was held out of a road match against Washington on Thursday. Stanford’s records show she continued to have distorted vision in her right eye Friday, yet was cleared by a team doctor over the phone Saturday to participate in a full practice and play in Stanford’s road victory over Washington State on Sunday.

The same team doctor examined Hodson on Monday and recorded her condition as “concussion, resolved.” Over the next two weeks, she played in four Stanford victories, twice leading the team in kills. On Nov. 26, she visited her parents for Thanksgiving. The Cardinal were playing UCLA the next day. At dinner, Hodson was edgy and irritable, her family said, telling them volleyball was an “off-limits topic.”

“She very much wasn’t herself, but we never even thought about the concussion,” Sonya says. “Once a kid gets cleared, nobody ever mentions it again.”

In the UCLA match, Hodson tried to block a hard shot. The ball ricocheted off her forehead and into the stands.

The Cardinal won in five sets. To this day, Hodson barely remembers the rest of the match. In her lawsuit, she claims she suffered a undiagnosed concussion during that match — and that Stanford did not evaluate her for a second brain injury.

Medical records reviewed by The Times do not indicate that Hodson was evaluated for a concussion during or following the UCLA match. A Stanford athletic department spokesperson declined to answer questions and said the school does not comment on pending litigation.

“Athletically,” Hodson says, “that was the last time I played well.”

‘Like climbing Mount Everest’

Following Stanford’s season-ending NCAA tournament loss to Loyola Marymount that Dec. 4, Hodson spiraled downward.

She couldn’t sleep. Her appetite vanished. Suddenly afraid to be alone, she called friends at all hours. She struggled to study for final exams. “Nothing was going into my brain,” she says. “Anything new, I couldn’t learn it.”

When her family took a holiday ski vacation, she mostly stayed inside, avoiding people and scribbling negative thoughts in a journal.

Hodson’s insomnia worsened when she returned to campus. So did the shin pain she had been experiencing since late in her freshman season. She had frequent migraines. She used to love exercise and hated sugary foods; now, she was perpetually exhausted and craved sweets.

Hodson struggled through Stanford’s spring season of beach volleyball. In March, she experienced vertigo on her way to the student union and nearly collapsed — something she says had happened following a concussion in high school.

On another day, Hodson says, she broke down sobbing in a training room. She says that Dunning called her into his office.

“I told him, ‘John, my mom is coming on a plane right now because I have been crying for the last eight hours. I don’t know what is going on, but I am not OK.’ ”

Dunning did not respond to a request for comment.

To treat Hodson’s shins, records confirm, Stanford athletic trainers gave her acupuncture and performed instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization, a painful process in which a metal tool was repeatedly pressed into her shins; to treat her lethargy, a sports dietitian recommended eating more carbohydrates.

For more than a decade, researchers trying to make sense of the mysterious degenerative brain disease afflicting football players and other contact-sport athletes have focused on the threat posed by concussions.

Before her sophomore season began, Hodson was named a co-captain.

“They were really counting on me to lead,” Hodson says, adding that she felt pressured. “I knew all the freshmen girls coming in, and I loved them so much. I wanted it to be a redemptive season after losing in the NCAA tournament.”

In early September 2016, Hodson’s parents visited Palo Alto. Jimmy had printed out a checklist of depression symptoms. In their daughter’s room, Sonya says, “I was checking them off, one after the other.” A Stanford psychiatrist, unaffiliated with the athletic department, diagnosed Hodson with clinical depression and prescribed Prozac.

During a match against Purdue, Hodson experienced dizziness, blurry vision and tingling in her fingers, all of which she says “happened to me during my concussion [in high school].” During her next match, against Cal Poly San Luis Obispo on Sept. 11, she felt a stabbing pain in her left foot, which swelled up and left her sidelined.

“That was a blessing,” she says. “[The coaches] couldn’t put me on the court.”

Sonya says that she asked coaches to redshirt Hayley during the Washington state trip. “They told me injuries are a part of the game and that I would just have to trust them,” Sonya says.

When the Cardinal returned to Stanford, Hodson says, “I was so depressed, I was walking across streets hoping I would get hit by a bus and die. Not actively suicidal. But I didn’t really care about life at that point. Or being on a court.”

Two days later, Oct. 4, Hodson took a medical leave of absence.

‘Working at 10 percent’

That December, Stanford defeated Texas to win the 2016 national championship. Hodson didn’t watch. Instead, she was meeting with a psychologist in Manhattan Beach.

Hodson still wanted to play. She read every self-help book she could, and met almost daily with doctors and physical therapists. She considered transferring.

The family did not trust Stanford. School doctors, Hodson says, had diagnosed her foot pain as inflammation and told her that she wasn’t risking further injury by playing. Medical records show that an independent doctor subsequently reviewed MRI scans taken by Stanford and determined she had a stress fracture.

On the day of title game, Hodson says, her mobile phone lighted up. “It was all sort of people I knew from volleyball,” she says, “saying things like, ‘Congratulations, this is your title, too.’ ” None of the messages, she says, came from Stanford.

Dunning retired in January 2017. His replacement, Kevin Hambly, visited the Hodsons at their Newport Beach home. “He said, ‘I can’t help you with what happened in the past, but I can help going forward,’” Sonya says. “‘If it takes to your senior year, I will help you love volleyball again.’”

Hodson was hopeful. By early March, her foot had healed. Her shins were pain-free. She planned to return to Stanford in April. But she was still struggling emotionally, and dealing with insomnia and listlessness.

While researching NCAA transfer and medical rules, Sonya had connected with Ramogi Huma, a former UCLA linebacker and executive director of the National College Players Assn., a nonprofit advocacy organization. Sonya mentioned that her daughter’s decline had started after she was concussed.

Go back in time, Huma advised. Start there.

Sonya and Hayley reached out to experts, starting with David Baron, a USC professor and neuropsychiatry researcher who has worked with many athletes. Baron said it was likely Hodson was suffering from post-concussion syndrome (PCS), a disorder in which symptoms such as dizziness, light sensitivity and intense headaches persist long after someone experiences an initial brain injury.

Post-concussion syndrome is a disorder in which symptoms persist long after the initial brain injury, often in response to physical or cognitive activity.

“Oftentimes, the symptoms look like depression or anxiety, and sometimes they are misdiagnosed,” says Baron, now the senior vice president and provost of the Western University of Health Sciences “But we see changes in moods, sleep, irritability. Those can be related to, and directly caused by, the effects of impacts to the brain.”

A lengthy evaluation by David Franklin, a clinical neuropsychologist at UC Riverside, confirmed Baron’s suspicions. Parts of her brain, Hodson says, “were working at 10%.”

Franklin said her impaired concentration and reaction time made it dangerous for her to continue playing volleyball, Hodson says. (Stanford doctors unaffiliated with the school’s athletic department subsequently came to the same conclusion.) Koutures, the Team USA doctor who had treated Hodson in high school, recommended she medically retire.

Hodson returned to Stanford in April 2017. She announced her medical retirement in June. In between, she worked as a production assistant for the Pac-12 Network on a beach volleyball match. By the end of the broadcast, she was shaking uncontrollably.

“I realized that volleyball was over for me,” Hodson says. “And that’s not what I would have chosen.”

Speaking out

Brain injuries are intensely isolating. A torn knee ligament can cut athletes off from their sport — but post-concussion syndrome can alienate someone from their entire life.

“You’re not you in a lot of ways,” Hodson says. “There’s invisible and silent suffering, days you are stuck in the dark. Looking other people in the eye can be difficult. Nobody knows how to deal with it. You lose friends. It’s just so lonely.”

To cope, Hodson shared her story.

On her blog, she wrote about trusting Stanford and feeling pressured to play through injuries. About spending a week at a brain injury clinic in Utah. About the loss of her Olympic dreams and a volleyball community that, she says, “felt like family.”

Stories started coming in return.

Hodson heard from Haylee Williams (née Roberts), a Bakersfield native she played against in club matches during high school. A top recruit in 2013, Williams went to Oregon, suffered a debilitating concussion during summer workouts and left the school before ever playing a match. Hodson also heard from Jordyn Schnabl, a Long Beach native who says that during her senior year at North Carolina in 2015, she took a ball to the head that produced a career-ending concussion diagnosis and left her with long-term symptoms including excruciating headaches and vertigo.

“I felt like I needed to reach out to Hayley,” Schnabl says. “I wanted to see how she was coping. And I wanted to know, ‘Am I an outlier, or is this systemic?’ It seems systemic.”

Hodson connected with Huma, the campus athlete advocate. She read articles and watched documentaries about abusive coaches and economic exploitation of young athletes. She learned that the NCAA says “safeguarding the well-being” of athletes is its mission, but it neither makes nor enforces binding concussion care and management rules for its member schools.

“There’s no accountability,” Hodson says. “There are good people in the system, but it’s not set up to look out for kids.”

Hodson’s lawsuit against the NCAA and Stanford is in discovery. According to her Los Angeles-based attorney, Robert Finnerty, a trial could occur next year or in 2022 depending on how the COVID-19 pandemic affects civil court scheduling.

“There are days where I am haunted. I was a really capable person before [my injuries]. Will I be 40 with dementia? If I hit a life crisis, will I spin out?”

— Hayley Hodson

In addition to damages for pain, suffering and lost volleyball income, Hodson’s suit seeks to force the NCAA to place brain injury warning labels on volleyballs; train college coaches and athletic trainers to recognize and properly treat brain injuries; and monitor and discipline those who fail to do so.

Contacted by The Times, a spokesperson for the NCAA declined to comment or answer questions about Hodson.

Now 24, Hodson still suffers from migraines and insomnia. She takes medication for depression and chronic fatigue, and sees a therapist for post-traumatic stress disorder. She needs extra time and a special note-taking app to complete her schoolwork and exams, and for a time lived by herself so that she could “come home to what is essentially a sensory deprivation room.” Hodson says that she has improved from “four hours of brain function a day to eight” but can end up exhausted and overwhelmed by daily life.

“There are days where I am haunted,” Hodson says. “I was a really capable person before [my injuries]. Will I be 40 with dementia? If I hit a life crisis, will I spin out?”

It would be easier, she says, not to litigate her brain injury — and easier still not to publicly discuss her trauma. “About every other day,” she says, “I’m like, ‘Why have I done this?’”

Hodson knows the answer: to advocate for other young athletes. She graduated from Stanford in June 2019, and this month is finishing her third semester of law school at UCLA.

Hodson recently connected with a volleyball player at a Division I school who suffered two concussions and subsequently struggled with her mental health. “When I was younger, I totally looked up to Hayley,” says the player, who asked not to be identified to protect her privacy. “She was the it volleyball player. Hearing her story was like, ‘I am not crazy.’ It was validation for what I was feeling and going through.” Rather than play hurt, the player took a medical leave. She’s now at home, recovering.

“We have kids all over the country that need to save themselves and don’t know how,” Hodson says. “If I speak out, then maybe someone else with something wrong will have the courage to speak out, too.”

Hruby is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.