These former Clippers might be ‘Knuckleheads,’ but people listen

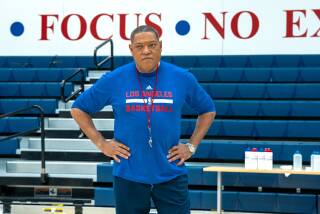

Two years ago, after being approached by the Players Tribune about creating a podcast, Darius Miles and Quentin Richardson set up the audio equipment for a test episode on Richardson’s back patio.

They were first-time co-hosts but had been friends since basketball brought Miles, a seventh-grader from East St. Louis, together with Richardson, a ninth-grader from Chicago. In 2000, when Miles was just 18 and Richardson 20, they became Clippers first-round draft picks and teammates.

The young Clippers weren’t on their way to three consecutive championships like the Lakers. They won 31 games in Miles and Richardson’s rookie season. Yet their youthful personality, amplified by magazine covers and highlight shows, seeped into the sport’s culture. They followed dunks with two taps of their knuckles to their heads, and what began as a nod to their friends at Westchester High, who originated the celebration, quickly became synonymous with Miles and Richardson.

Scheduling the podcast demo was easy. In retirement, the two lived only seven minutes from one another in Orlando, Fla., and their first guest, former NBA forward Drew Gooden, walked over from his house across the street. Without experience to draw from, and with drinks in hand, they began to riff as if the microphones weren’t even there.

“The more we drank, the more curse words started to come out,” Richardson said. “By the end of it, it was like all of us yelling over each other.”

The Clippers’ first moves of free agency became official late Wednesday after the team announced the contracts of forwards Marcus Morris, Patrick Patterson and Serge Ibaka.

To listen to Miles and Richardson now, five seasons and 61 episodes into their show, “Knuckleheads,” is to hear seasoned podcasters with a refined style. They don’t curse as much. They aren’t as generous with their drinks. What hasn’t changed, however, is their intent of making listeners feel as though they are eavesdropping on a raw basketball conversation between teammates.

“That was our aim, to have our vibe kind of like when we on the bus, we in the plane, in the locker room, things like that,” Richardson said. “We wanted to have that type of comfort level.”

Aligning themselves as a guest’s teammate, of sorts, was intentional.

“I don’t think we ever look at ourselves as media or as the interviewer and all of that,” Richardson said. “We born hoopers. We played in the NBA. We part of that fraternity, nothing can ever take us away from that. We never going to violate that, so we that before we anything and everybody identifies us as that, and that’s where that comfort zone comes in because they talking to one of their own.”

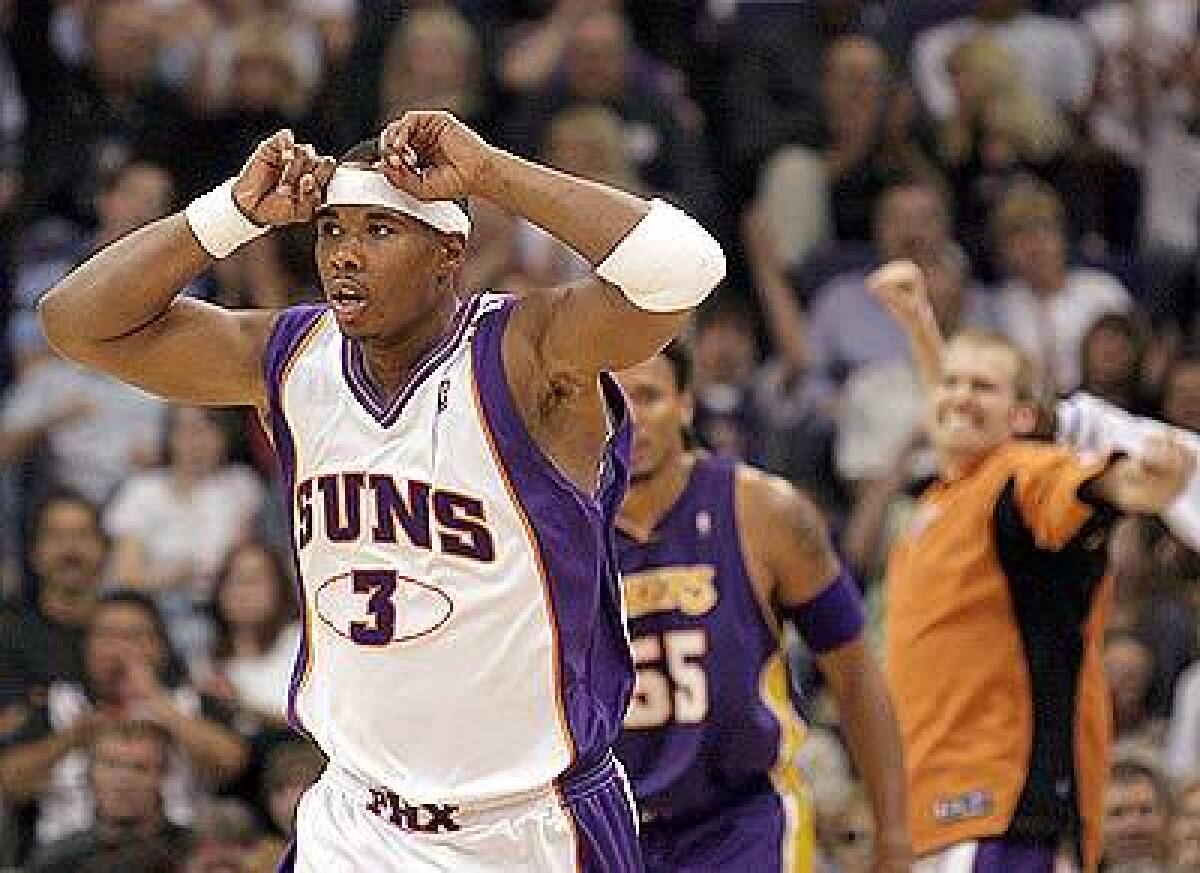

The approach has helped guests, including Kobe Bryant, Allen Iverson, Steve Nash, Kevin Durant, Rasheed Wallace and A’ja Wilson get comfortable. It has also created an unexpected second act for the hosts’ basketball careers. The show has a perfect five-star rating on Apple, with more than 2,000 reviews.

Miles, the former 6-foot-9 forward, initially took longer than Richardson to warm to the idea of a media collaboration. He’d largely been out of the spotlight since his 2009 retirement, but has since likened talking to his friends and idols on the show as “like a kid in the candy store.”

Interviewed four months before his January death, Bryant recounted his motivation to prove Charlotte’s general manager wrong after the Hornets traded him on draft night. Wilson Chandler talked about celebrating his own first-round selection by riding a bicycle around his neighborhood, drinking Cristal champagne. Dikembe Mutombo told the story of being discovered by coach John Thompson while at Georgetown on an academic scholarship. Episodes begin with guests posed the same basketball icebreaker: Who was the first opponent to humiliate you as a pro rookie? Baron Davis said John Stockton “embarrassed me.”

Miles is more apt to guide guests into talking about memorable games or specific dates. Richardson, the 6-6 former guard, sees his role as helping guests display the personality he and Miles see to a wider audience.

The show’s 11-episode fifth season, which began last week, was recorded amid the pandemic, which required changes from the previous format in which the hosts sat around a table with guests, often with a glass of Hennessy in hand. Staying at home has made booking reclusive guests easier but the “energy in the room” can’t be replicated over Zoom, Miles said.

“But once me and Q talking, we joking back and forth, and it just gets free, the air gets free,” Miles said. “You just laughing, joking, reminisce on people’s great careers and tell them how much we appreciate what they’ve done.”

“Knuckleheads” is part of an industry whose advertising revenues are projected to approach $1 billion in 2020, said Sue Hogan, the senior vice president of research and analytics at the Interactive Advertising Bureau. Podcasting’s projected 15% revenue growth from the previous year is only half of what was projected — a reflection of the impact COVID-19 has had on advertising spending across a wide array of media. Hogan said podcasting’s outlook remains strong, though, with revenues expected to exceed $1 billion in 2021.

Numbers like that have not only caught the attention of analysts but athletes, even those years away from retirement. In August, after hosting dozens of episodes of his own show for the Ringer, New Orleans guard J.J. Redick formed his own production company, telling the New York Times that he hoped food and politics shows could come next. That same month, Durant became an executive producer of his own podcast network, which produces the show he hosts.

The Clippers might have to turn to trades now to revamp their roster, with Patrick Beverley, Ivica Zubac and Lou Williams potentially on the block.

Miles and Richardson believe the isolation during the first months of the pandemic accelerated the popularity of podcasts among athletes seeking creative outlets while also controlling their own communication with fans. In the future, they see players approaching retirement with an eye on podcasts instead of hunting for coaching or front-office jobs or traditional media roles, such as television.

They wonder what their reach would have been had social media and podcasting existed during their brief stays with the Clippers. Miles played two seasons with the team while Richardson stayed for four. The team’s cultural significance, from the clothes they wore to the personality they played with, belied its on-court success. An ESPN show followed the team, with nearly half the roster under the age of 21. Magazines put them on covers.

“We were representing the youth because we were the youth at the time in a grown man’s league,” Richardson said. “If you had social media we would have been everywhere because we stayed in the malls, we stayed just being very visible. The opposite of us were the Lakers. … They were all basically married and kind of an older team. Our core players, four, five, six of us, were all under 20. We were really out there, at the clubs, in the colleges, going to the high school games. We were of that culture.”

Two decades later, amid the saturated world of sports podcasting, they again find themselves attempting to stand apart. They have done so, Miles said, by again staying as “real as possible.”

Microphones or not, on a patio or over Zoom, they would be having these conversations with their famous friends anyway.

“With me and Darius, this is over 25 years of friendship,” Richardson said. “This is something that we been doing before, and would be doing if it wasn’t here, and still going to be doing that if it ever leaves.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.