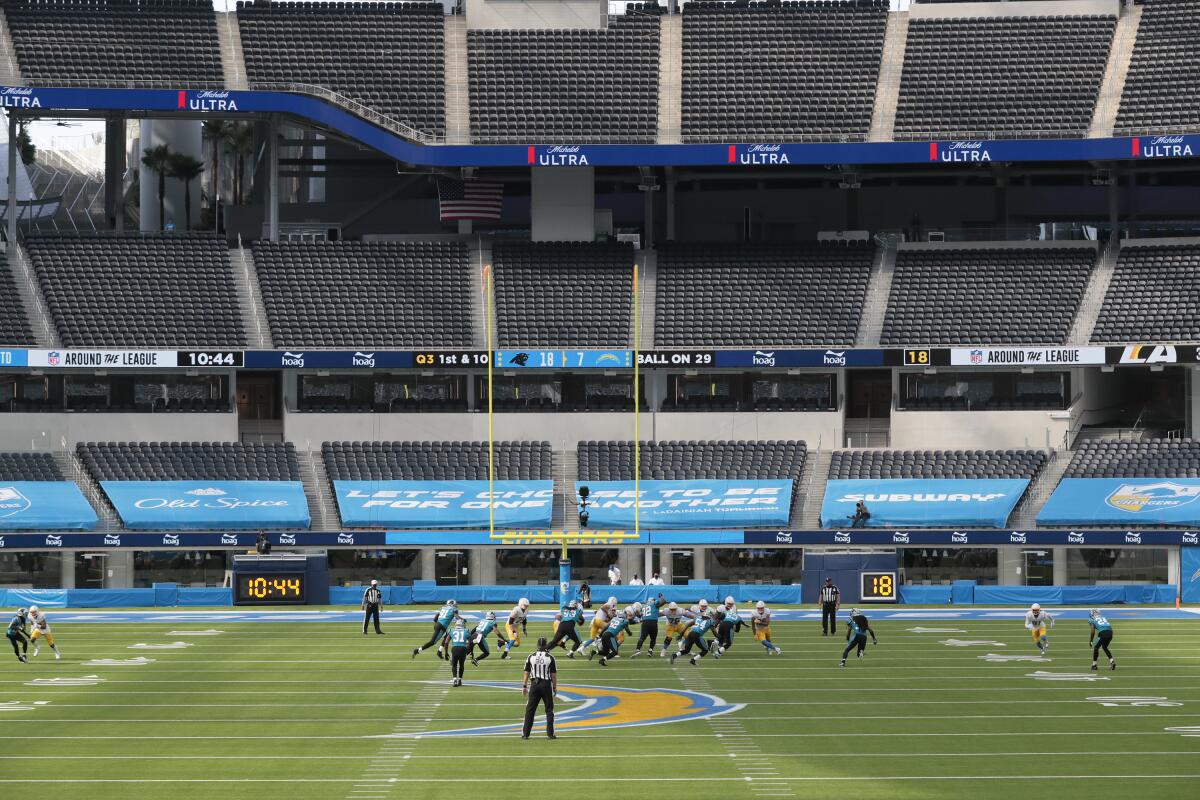

It might sound a bit odd, but NFL is making some noise by re-creating fan reactions

Let’s hear it for the NFL.

NFL Films executive Vince Caputo is certainly listening. For him, football is as much about the sounds as the sights.

He headed a years-long NFL Films project to build a massive database of crowd sounds from every stadium, not knowing that audio library would be so valuable in an age of empty venues and artificial noise.

Now, as the backdrop to TV broadcasts, the cheers, boos, and everything in between are actual recordings from previous games of the home team.

So they’re caterwauling Cowboys fans, bona fide Bills backers, Lions faithful with lungs of leather.

“We tried to leave as much character in as we could,” said Caputo, NFL Films vice president and supervising sound mixer, whose team began collecting crowd-centric recordings in 2016.

The NFL postpones the Pittsburgh Steelers game at Tennessee until later in the season after another Titans player and a personnel member test positive for COVID-19.

Then, they undertook the painstaking process of extracting all the music and public-address announcements from the audio so they would have pure sound to use in shows and other productions.

It was not an easy task for Caputo and his team of nine staff mixers, who after collecting the audio spent months of exacting sound surgery.

“In the Giants recording, there’s a kid yelling in one of the mics — I’m guessing he was about 10 years old — he’s just yelling, ‘Let’s go Eli!’ through the entire game,” he said. “The guy [quarterback Eli Manning] is retired, so every time that came up, we had to cut that out.”

All of that material became incredibly valuable this offseason when the NFL decided to pipe artificial noise into games during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I might drop it out for a series this week to let people hear what they’re not missing.”

— Fred Gaudelli, executive producer of “Sunday Night Football” on NBC, on recorded crowd noise used on NFL broadcasts this season

There are two basic audio streams: the one that millions of viewers hear in broadcasts, which ideally is dynamic and responsive to what’s happening on the field, and the unwavering white noise that players hear, which cannot be turned up higher than 80 decibels, roughly equivalent to the sound of a lawnmower.

“If we took these games and played them without the sound, I think it would be a really miserable experience to watch it,” said Fred Gaudelli, executive producer of “Sunday Night Football” on NBC. “You’d be missing a critical element that keeps your attention, gives you energy, builds anticipation. I might drop it out for a series this week to let people hear what they’re not missing.”

Each of the 32 teams has a “playback operator” who sits somewhere in the stadium or outside in a production truck, watches the game, and punches up the appropriate crowd sound for the situation. Only the home team operator works the game.

Because the reactions have to be immediate, the operator has a fairly simple controller with 10 buttons for various reactions, along with two faders — sliders to move the intensity level up and down.

In hiring the operators, Caputo said, “we had to find a balance of people who had an audio background to interface with the production trucks, and we wanted everyone to be local and a fan of the team, and certainly know the game.”

The sound provided by the operator is fed to the network production crew, which then decides how to use it in the broadcast, whether it’s bringing up the volume, tamping it down, or keeping it the same.

“You can’t just put noise in for noise sake,” said Joe Buck, play-by-play announcer for Fox. “It’s got to be done smartly.”

So far, it’s a work in progress. The operators are learning on the fly, and they didn’t have preseason games this summer to practice.

“One of the difficulties we had in Week 1 is they just wanted to be so right with everything,” Caputo said. “So they would kind of wait for the play to resolve and then fire the exact right reaction. It’s way too late by then.

“We reminded these operators that if you’re a hometown fan, you think every play is going to go your way until it doesn’t. So that ball’s going down toward your receiver, you want to fire that positive reaction and get excited. And if things go bad, it gets batted away or intercepted, then you can hit a negative reaction. That would be the natural reaction of the crowd.”

Instead, what was happening too often was: Touchdown … lull … Hooray!

NFL tells teams they could be stripped of draft picks if coaches flout mask rules.

“I’m on Red Zone or flipping through the games, and I’m starting to lose my breath because every time I watch a play, it’s over and I just cross my fingers, like, ‘OK, don’t fire a reaction now,’” Caputo said. “And then all of a sudden, ‘Yay!’ My wife was losing her mind.”

In Kansas City’s game at Baltimore on Monday night, a Chiefs ballcarrier gained a few yards and was tackled by a cluster of defenders on a run-of-the-mill play. What followed was an incongruous eruption of cheers from make-believe Ravens fans.

“We’ve had some misfires,” Caputo conceded.

But the operators are getting better at anticipating reactions and building to a crescendo.

“When it’s done well,” Buck said, “it feels like a Jedi mind trick. … People want to be taken away by these games. And part of that is having this sound that we’ve always provided.”

Just what Caputo wants. Everyone playing it by ear.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.