Michael Jordan won’t apologize for the ugly side of his greatness

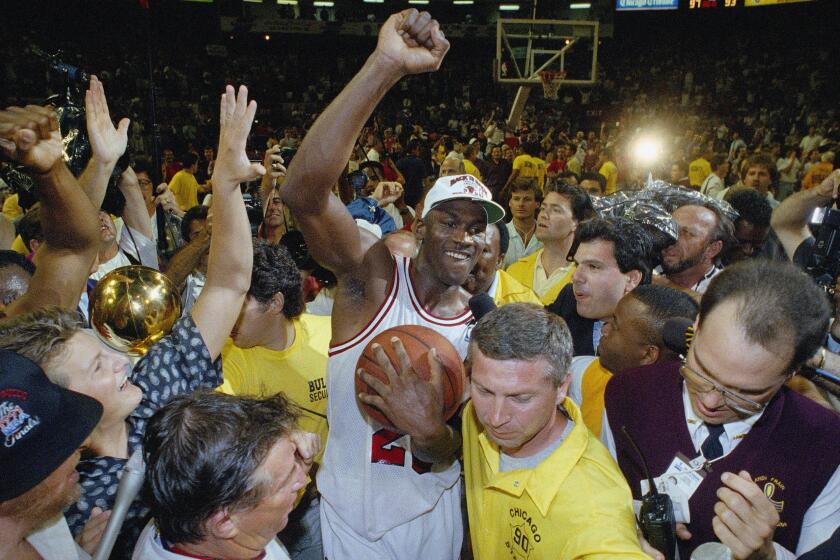

After the Chicago Bulls won their fourth NBA championship, on Father’s Day in 1996, Michael Jordan collapsed on the floor of the Bulls’ training room at the United Center. It’s one of the most poignant scenes of the first eight hours of “The Last Dance.” As cameras roll, a prostrate Jordan — playing his first Finals since the murder of his father, James — heaves and sobs in a collision of triumph and grief.

Is it worth it? That’s the question the “The Last Dance” implicitly asks over and over. Jordan’s answer is a definitive “Hell, yeah.”

That scene is where we will pick up the final two episodes, which air Sunday night. I will have given way more than 10 hours to ESPN’s mega-project, watching and re-watching episodes, tunneling down endless YouTube rabbit holes of low-definition highlights and silly commercials that feature the team of my youth.

It’s been fun — tons of fun. When the series ends, I’ll have a greater appreciation of Jordan’s hunger to win and the results it forged. I also will be as uncomfortable with the methods behind his inarguable genius, however successful they were.

“When people see this, they’ll say, ‘He wasn’t really a nice guy. He might’ve been a tyrant,’” Jordan says at the end of Episode 7. “Well, that’s you — because you’ve never won anything. I wanted to win.”

Coverage of ESPN’s “The Last Dance” series, featuring behind-the-scenes stories about Michael Jordan, the Chicago Bulls, Kobe Bryant, Carmen Electra and more.

The moment comes across like a pre-battle monologue from “The Avengers,” a prelude to a montage of heroic achievement set to a motion picture soundtrack. But is the viewer to believe Jordan is more heroic, or less, having been offered such a voluminous, if carefully packaged, rendering of his career and legacy?

On the court, the documentary has reinforced everything lifelong Jordan watchers, like me, already thought about him. Watching Jordan dance around the 1986 Boston Celtics, the 1997-98 Bulls of their day, it’s clear he was ushering in a new, advanced era of basketball.

His performance is without equal. Seeing Jordan morph into modern basketball’s greatest champion, seeing him master the triangle offense, watching him defer to teammates at the most critical moments (see: Paxson, John), it’s the kind of airtight greatness that makes Jordan the standard for everyone who took the floor after him.

In the final two episodes, watching the Bulls grit through a series against the Indiana Pacers, seeing Jordan grind through fatigue and the flu against the Utah Jazz will offer the last confirmation of Jordan’s unparalleled status. And it will erase any lingering notion that the Bulls’ championships came easy.

But there are gray corners too. Did Jordan have to be such a jerk? Did he have to step over and through so many people? Why was Jordan’s greatness so attached to loneliness, to the point where he spent much of the back half of his career in an emotional quarantine? Why was he — and is he, still — so petty?

To be the player, the winner, the competitor he was, that stuff seemingly needed to happen. At least, that’s Jordan’s version of the story. He bored easily. (He did, after all, boast half as many retirements as he did championship rings.) It’s especially ugly to watch Jordan still revel in these past rivalries, to see him dismiss Clyde Drexler, Gary Payton and the others who were worthy adversaries.

But seeing these warts in HD hasn’t made Jordan any less magnetic. It’s why people like me have stared at the sneakers he wore in his prime and still considered making impulse purchases. It’s why some NBA executives, older than me, have flirted with buying Jordan jerseys.

And, it’s why more than 20,000 people — tennis champion Roger Federer being one of them — got onto their Peloton bikes at 10 Saturday morning to ride to the soundtrack of “The Last Dance” with instructor Alex Toussaint, who wore Jordan’s famous red No. 23.

During that ride, Toussaint barked that Jordan never asked anything of his teammates that he didn’t demand of himself. With that, I pedaled faster for no reason other than I thought it’s what Jordan would’ve demanded of me.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.