That .202 hitter Michael Jordan was a better MLB prospect than, say, Tim Tebow

Charles Barkley held court in the middle of the Angels’ clubhouse one day this spring. He talked about Mike Trout and Bryce Harper, about Shohei Ohtani and Bo Jackson, about Kobe Bryant and Stephen Curry.

And then the conversation turned to Michael Jordan, and to my contention that he had been pretty good at baseball, all things considered. Barkley swatted me away as if I were a lazy jump shot.

“Stop bragging about a guy hitting .200,” Barkley said.

The two most famous minor leaguers of the past quarter-century are Jordan and Tim Tebow. That is often framed as an example of baseball’s marketing incompetence, but the pretense that a star turn in the College World Series can juice name recognition like three NBA most valuable player awards or a Heisman Trophy is ridiculous.

Michael Jordan often created a rivalry with an opponent like LaBradford Smith over a perceived slight to help fuel a desire to dominate on the court.

Credit Jordan and Tebow for the willingness to stray from their sporting comfort zones, to risk embarrassment, to dedicate themselves to a craft at which they would be unlikely to succeed.

But know this: One of those guys could have developed into a legitimate major league prospect. Tebow is not the one.

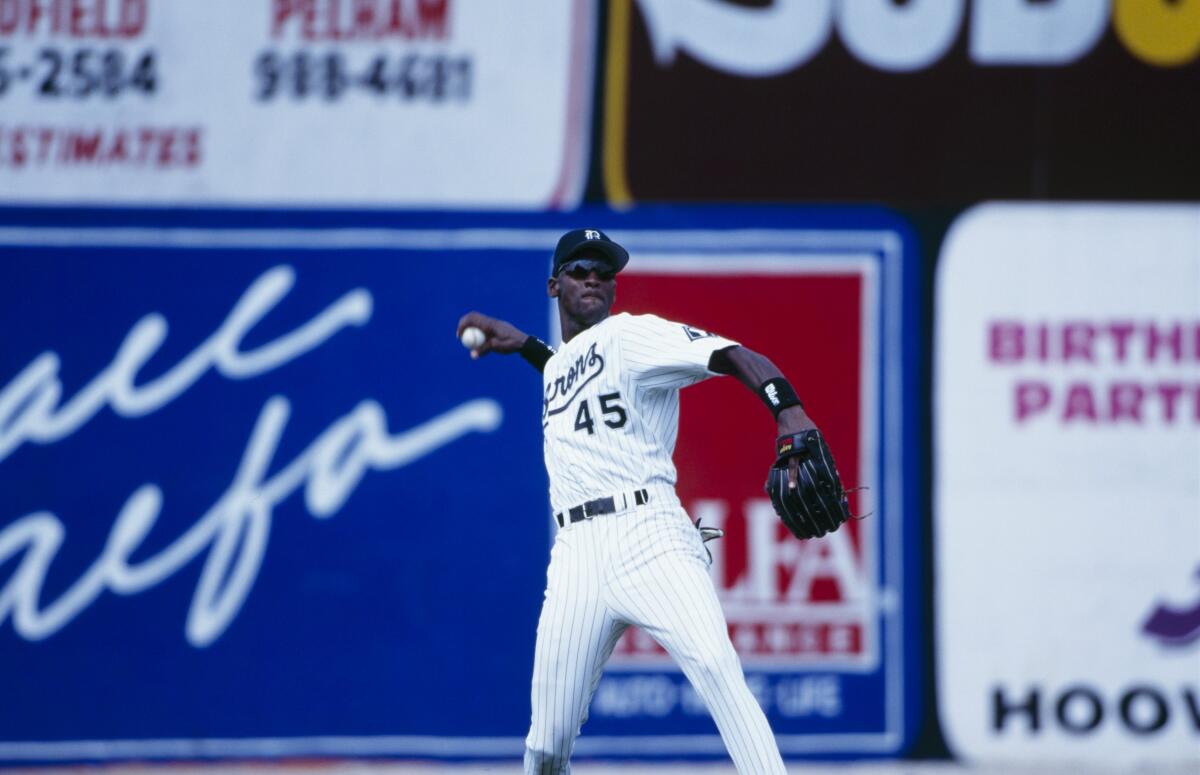

On Sunday, “The Last Dance” turns its attention to Jordan’s 1994 baseball sabbatical. The mythology that it was a failure was fueled largely by the Sports Illustrated cover that read “Bag It, Michael!” The accompanying story appeared before he had played a single minor league game, and the premise that he somehow had disgraced a Chicago White Sox team that had last won the World Series in 1917 was absurd.

The Oakland Athletics, as it turns out, got wind of Jordan’s baseball dreams and offered him a major league roster spot. Jordan remained loyal to Jerry Reinsdorf, owner of the White Sox and the Chicago Bulls.

The White Sox dispatched Jordan to double-A Birmingham, where he batted .202 with three home runs in 436 at-bats. He stole 30 bases, but was caught 18 times. He led Southern League outfielders with 11 errors.

“Other than not having the power, he was the greatest athlete we’ve ever seen,” a White Sox official said.

Jordan was 31. He had not played baseball since high school. Most minor leaguers don’t even make it to double A. So, yeah, Mr. Barkley, I’ll say that was a pretty good season, all things considered.

“I agree,” Sal Butera said.

Butera is a former major league catcher, and the father of former Dodgers and Angels catcher Drew Butera. He currently scouts for the Toronto Blue Jays. We called him because we wanted to check with a baseball guy who had been around long enough to have evaluated both Jordan and Tebow.

Jordan first, and with it Barkley’s contention that a .200 batting average represents failure, at any level.

“Charles is looking strictly at the statistic, at the number,” Butera said. “But, when you view a player, you look at the process. For Michael not to play, and then all of a sudden perform?

“Baseball is a very difficult game to play when you take off a month.”

Jordan had given the previous dozen years of his life to basketball.

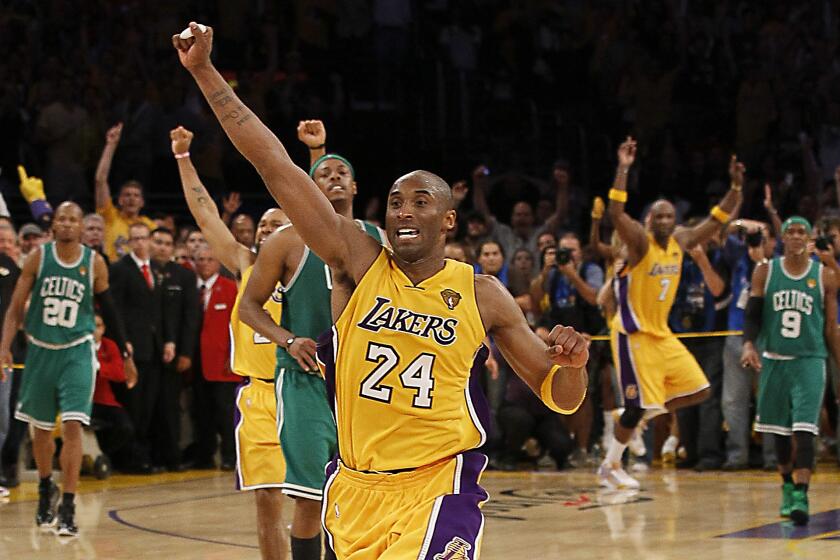

Could a mismatched band of defending champions gain revenge for a 2008 Finals embarrassment against the Celtics and become eternal Lakers?

“His body, being that long and that angular, was a hindrance,” Butera said. “Having long arms is good for some things, but bad for others.

“He glided on the basketball court, but he didn’t really run when he ran on the baseball field. He had speed, but it was choppy. He could still move, but not with that same ease you saw on the basketball court.”

That could have been repaired with repetition, for which there is no substitute in baseball. Along the way, he might have picked up some power, which is generally the last skill to develop. But success would remain elusive until and unless he had committed years to baseball.

“Your muscle memory as a player is so key to your performance,” Butera said. “You have to fall back on something.

“When Michael Jordan drove to the basket or pulled up for a jumper, he did those things in his sleep. In baseball, you can’t do that. Great players who have played the game their whole life can do that, but not somebody who’s been removed that long. It takes time. There is no substitution for the work.”

Jordan, in his only year playing baseball, had a .289 on-base percentage and a .266 slugging percentage. He struck out in 26% of his at-bats.

Tebow, 32, has played three minor league seasons, for the New York Mets. He struggled at Class A in 2017 and had moderate success at double-A, batting .273 with a .734 on-base-plus-slugging-percentage. Promoted to triple A last year, he batted .163 with a .240 on-base percentage and a .255 slugging percentage. He struck out in 41% of his at-bats.

“Tim really wants to play at the big league level,” Butera said. “He’s put the time in. He’s gone to spring training. He’s done the instructional league. He is a huge draw. He plays hard. People love him.

“He’s made strides, but not enough strides to say he is a major league prospect.”

Jordan could win the adoration of white America, but only as long as he didn’t talk about what it meant to be black in America.

Jordan could have been one, had he stuck with baseball. Scouts say most players cannot be properly evaluated until they collect 1,000 plate appearances in the minors. Tebow has 1,048. Jordan had 497.

Butera thought back to what one of his managers, Pete Rose, used to tell him. Rose always said basketball players were the best athletes.

Asked whether Jordan or Tebow would have been the better major league prospect, Butera did not hesitate to answer. The reference to Rose’s baseball sin was the bonus in the answer.

“I would have put my money on Michael,” Butera said, “if I had to bet.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.