Michael Jordan’s gambling explained: ‘I love to bet’

The first five episodes of ESPN’s documentary on the 1997-98 Chicago Bulls, “The Last Dance,” often cast Michael Jordan as nearly invincible — conqueror of villains (Isiah Thomas, the Bad Boys) and a worldwide basketball celebrity who could prompt even Larry Bird to gush that the guard was really “God disguised as Michael Jordan.”

The sixth episode, which aired Sunday, examined the ways that competitiveness manifested itself off the court.

You don’t think Jordan liked to gamble? Want to bet?

Gambling stories are as interwoven with Jordan’s career as those of his six NBA championships, forever linking him to high-stakes golf wagers, late nights in Atlantic City and fueling a conspiracy theory — which is just that, a conspiracy theory — that an image-conscious NBA nudged Jordan into his first retirement, in 1993, following league investigations into money he owed to cover gambling losses.

Jordan, in the documentary, says his addiction was to competition, not betting, but previous episodes of “The Last Dance” have already shown how the two mixed. After a Super Bowl victory by the Denver Broncos, Jordan, on a team plane, is seen telling teammates to pay up. And just after he entered the NBA, Scottie Pippen recalled that Jordan purchased him a new set of golf clubs, a gift disguised as a means for Jordan to take Pippen’s money on the course.

But Sunday’s episode goes deeper on Jordan’s gambling. Here’s a primer on that history:Where do we start?

Jordan’s feral competitiveness was well established early in his career, but his betting exploits reached a more public level in 1991 when Jordan spent a two-day break between playoff games against Philadelphia in Atlantic City, N.J., gambling all night with Chicago Sun-Times writer Mark Vancil. Vancil said the two walked into the Bulls’ Philadelphia hotel around 6:30 a.m., just as coach Phil Jackson was walking out.

That year, IRS officials investigating James “Slim” Bouler, a convicted cocaine dealer, on drug and money-laundering charges discovered a $57,000 check from Jordan. At first, Jordan and Bouler said the money was a loan for a driving range Bouler planned to build, but in 1992 Jordan testified in federal court that the money covered gambling losses from a weekend in South Carolina. Also in 1992, an investigation in North Carolina into the death of a slain bail bondsman named Eddie Dow found a briefcase containing three checks from Jordan totaling $108,000. Dow’s attorney and brother said the checks were for gambling debts owed by Jordan, The Times reported.

“The only people who are saying Michael Jordan is having a gambling problem are the people who don’t know Michael,” Bouler told the Washington Post in 1993, adding that he loaned Jordan money to play high-stakes card games in order to receive a percentage of the star guard’s winnings. “Some people love to eat. Some people love to fish. Some people like to hunt. Some people like to drink beer. And some people love to gamble. Michael Jordan loves to gamble.”

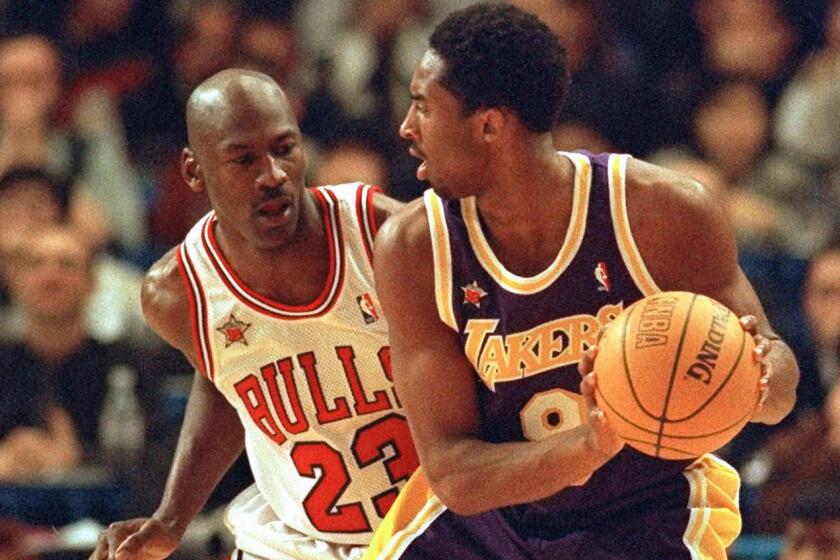

The story of Kobe Bryant and Michael Jordan sharing the court the last time on March 28, 2003, when the kid scored 55 points and the G.O.A.T. had 23.

What happened in 1993?

That May, the New York Times reported that Jordan had been seen at an Atlantic City casino at 2:30 a.m. on the eve of an Eastern Conference finals game against New York. Jordan acknowledged going to Atlantic City with his father but said he was in bed by 1 a.m.

Less than one month later, Richard Esquinas, a self-described recovering gambler, released a book “Michael and Me: Our Gambling Addiction ...My Cry For Help!” that claimed Jordan owed him $1.25 million in gambling losses from golf matches they played near San Diego. The Bulls guard won back some money during rounds played months later to reduce his debt to $902,000, Esquinas told The Times in 1993. After having difficulty collecting from Jordan, Esquinas said he further reduced the amount to $300,000, an amount Jordan agreed to pay.

“He exaggerated to a point, and I’ve come up with my own conclusion to why he exaggerated,” Jordan told Ahmad Rashad before the 1993 NBA Finals. “… It sells books.”

Esquinas’ claim prompted a second NBA investigation led by Frederick Lacey, a former federal judge. Before it concluded, the 30-year-old Jordan retired on Oct. 3, 1993, saying in part that he had lost his competitive fire.

Episode 5 of ‘The Last Dance’ is dedicated to Kobe Bryant. It features Magic Johnson recalling Michael Jordan’s relationship with Bryant.

“Five years down the line, if the urge is there, if the Bulls would have me back, if David Stern would let me back, I may just come back,” Jordan said. The line concerning the NBA’s commissioner continues to fuel a belief that Jordan’s return to the NBA was conditional on cleaning up his reputation as a bettor. No evidence has ever proven such a theory.

Two days after Jordan’s announcement, Stern said Lacey’s completed investigation concluded that “absolutely no evidence Jordan violated league rules” and added there was no connection between that investigation and the star’s retirement.Any good stories about Jordan’s high-stakes gambling?

Several. Jordan’s desire to win took aback even fellow professional athletes. Former Chicago Blackhawks star Jeremy Roenick told a radio show that in 1992 the pair played 36 holes of golf the day of a Bulls game and that Roenick had won a few thousand dollars off Jordan.

“Now we’ve been drinking all afternoon, and he’s going from Sunset Ridge to the stadium, to play a game. I’m messing around. I’m like, ‘I’m gonna call my bookie. All the money you just lost to me, I’m putting on Cleveland.’

“He goes, ‘I’ll tell you what. I’ll bet you that we’ll win by 20 points and I have more than 40 [points].’ I’m like, ‘Done.’ Son of a gun goes out and scores 52 and they win by 26 points or something.”

Jordan never scored 52 points in a game during the 1992 calendar year, but he did score 44 in a 24-point win against Cleveland on March 28.

In 2017, Charles Barkley described the different level of stakes Jordan played for.

“We’d be playing golf with certain people, and we’d be playing a couple hundred dollars a hole, enough to bet, and he’d be playing some guy for like $100,000,” Barkley told “The Dan Patrick Show.” “He’s like, ‘Charles, pick that up.’ I’m like, ‘This putt is for $200.’ He’s like, ‘Pick that up, Charles. Get out of my way, you’re in my line.’ I said, ‘Well how much is that putt for?’ He’s like, ‘$300,000.’ I said, ‘Let me get out of your line.’ It was crazy, man. They were playing for hundreds of thousands of dollars. It was crazy.”

What has Jordan said about his history of gambling?

“Jordan denies nothing, insisting on his right to associate and wager with anyone he chooses,” The Times’ Mark Heisler wrote in 1992, after links to Bouler and Dow became public. “‘The mistake, first of all, was that it got to be a public-knowledge situation.’ he said. ‘I love to bet. That’s a part of everyone’s competitive attitude.’ ”

Asked about his gambling in “The Last Dance,” nearly three decades later, Jordan reiterated that he “didn’t do anything wrong.”

“I never bet on games,” Jordan said. “I only bet on myself, and that was golf. Do I like playing blackjack? Yeah. … The league called me and asked questions about it. And I told them.”

Asked whether he had a gambling problem: “No, because I could stop gambling. I have a competition problem, a competitive problem.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.