Kobe Bryant’s death is painful reminder to Loyola Marymount of Hank Gathers’ death 30 years ago

The text confused Tom Peabody. A friend had sent him a cryptic, expletive-laden message about Kobe Bryant late on a Sunday morning in January. Peabody was grabbing a bite to eat with his son, and he quickly searched for more information. At first, he came up empty, but then, he found something about a helicopter crash in Calabasas.

His heart sank into his stomach. He texted his friend back: “I am so stunned.”

Thing was, the shock that overcame Peabody was not a new sensation. As time passed, it became all too familiar.

“When I saw that happened,” Peabody said, “it kind of gave me that same feeling. It’s the first time I’ve felt that in 30 years …”

For Peabody and the rest of the 1989-90 Loyola Marymount Lions, it doesn’t take much to remind them of their fallen friend, Hank Gathers.

Usually, they recall the uplifting stuff — his dominance on the court as the nation’s leading scorer and rebounder, the exuberance he brought to his everyday life and the way he was somehow with them as they captivated the nation with three NCAA tournament victories.

Three UCLA freshmen were the heroes behind a stunning victory over Arizona State on Thursday, showcasing a glimpse of a very promising future for the Bruins.

They try not to think of his collapse on the court during the West Coast Conference tournament due to sudden cardiac arrest, the trepidation of waiting for news from the hospital and the pain of learning their leader, the man who claimed he had a “heart the size of a lion,” was gone.

But Bryant’s death took some of the Lions back to that dark place and a moment that shaped each of them right as they were entering adulthood.

“Immediately, Hank popped in your head,” said Brian McCloskey, a redshirt freshman on that team. “Obviously, the Kobe thing is tragic, but Hank didn’t even get a chance to play in the NBA. That’s the sad part. He didn’t get a chance to do a lot of things.”

Among the former Lions, it wasn’t just the unthinkably tragic way they died that connected Bryant and Gathers on January 26.

“They’re both Philadelphia guys,” said Peabody, a scrappy guard for LMU who is now a San Diego-area attorney. “There are a lot of similarities with their approach to life. Everybody talks about the Mamba Mentality. Hank had the mentality. He was a tireless worker. There’s just not a lot of people who have that. It would have been nice to see Hank’s post-basketball life.”

On Saturday, many of the Lions will gather for the unveiling of a statue honoring Gathers outside LMU’s Gersten Pavilion just days before the 30th anniversary of his passing March 4.

As hard as it may be for some to not be filled with regret at what Gathers didn’t accomplish, his best friend, Bo Kimble, has never thought of it that way.

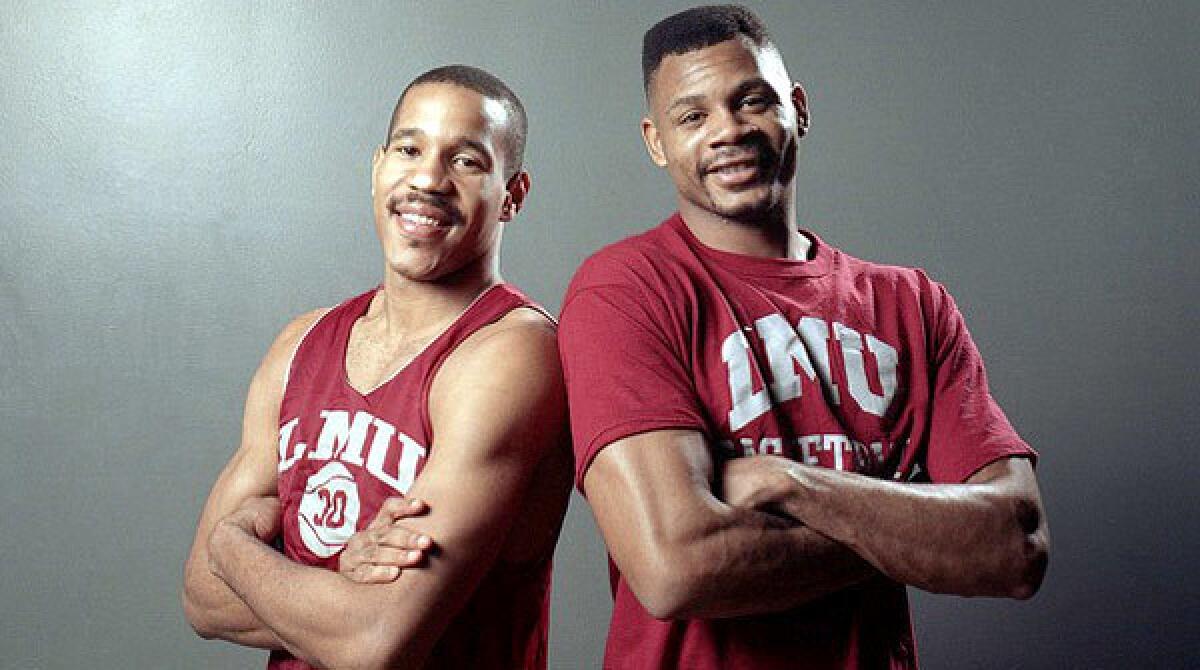

“Hank Gathers was a superstar while he was alive, being recognized all over Los Angeles and nationwide,” said Kimble, who played with Gathers at Dobbins Technical High in Philadelphia before joining him at USC and then LMU.

“He was a thousand-watt light walking into a room with 100-watt light bulbs. He just lit up. Hank was extraordinarily happy, and I said this often: Hank did in 23 years what some athletes and some people have never achieved in 100 years of life, to be an iconic figure, a person who was respected on and off the court, a person who was living his dream.”

For two weekends in March of 1990, the Lions took the stage without Gathers, and the nation followed along, rapt. If college basketball fans hadn’t been introduced to the beautiful frenzy of Paul Westhead’s “The System” before the tournament, they were now being treated to the head coach’s opus, combining the confidence all of his players felt to shoot the ball as soon as they got it in their hands with a composure that seemed to be aided by the supernatural.

Gathers took to shooting free throws left-handed, his off-hand, in hopes of improving in an area he struggled, so there was the right-handed Kimble shooting his first free-throw attempt in each game with his left, making all four. There was three-point marksman Jeff Fryer, making an NCAA-record 11 three-point shots in the Lions’ 149-115 second-round upset of Michigan, the defending national champion.

“The players performed on the one hand to honor Hank Gathers, but on the other hand to forget for two hours the pain and suffering that they were going through,” Westhead said. “Playing the game gave them some relief from their sorrow. They played not necessarily trying to win. You get in the tournament, it’s win or you’re out, but that wasn’t their concern. They just wanted to play and perform.”

Westhead had designed a style that was supposed to be fun, above all else. But to be able to full-court press the entire game and push the ball up the floor fast enough to shoot within the first 10 seconds of the shot clock for 40 minutes, the Lions had been pushing the limits of their lung capacity dating back to summer conditioning sessions on the nearby Manhattan Beach sand dunes.

“I still tell my kids about that,” McCloskey said. “Guys learned quick not to eat lunch before you go to the sand dunes.”

The tradeoff for getting through Westhead’s workouts was that, when the season started, players had the green light to shoot the ball whenever it touched their hands. Fryer remembers Westhead pulling him from a game because he passed up a shot.

In the tournament, each Lion simply performed their role as it had been laid out for them. They were perfectly in sync. When the magic ran out in the Elite Eight against eventual national champion Nevada Las Vegas in a 131-101 defeat, they had become an inspiring part of college basketball history.

The players’ challenge in the months and years that followed was to find fulfillment removed from the spotlight.

“When that season ended, the reality for me is, there was no way I was ever going to recreate that,” Peabody said. “I was kind of an intense guy, an adrenaline junkie, but that was a once in a lifetime experience.”

Most of the Lions would not go on to professional basketball, instead trying to use the lessons they learned from the spring of 1990 to help launch their business lives. But Fryer now had the task of trying to start his basketball career while beginning to confront life’s big questions.

“Hank’s passing really got me thinking about life and death and what happens when I die,” Fryer said, “because I wasn’t raised in a family that went to church or anything. It was kind of a spiritual journey, and I actually had to hit some hard times through that.

“It was tough at the beginning, and I would think about him often. There were different ways that I would try to mourn and think of him. When I was at the Portsmouth camp for NBA tryouts, I would tell myself, ‘Play with Hank’s toughness.’ ”

During a recent phone call, Fryer paused to gather his emotions.

He played in the CBA and overseas, seeing the world and living a childhood dream that did not stack up to his time playing at LMU.

“That was probably the pinnacle for me personally in my basketball career,” Fryer said, “and everything after that was kind of secondary it felt like, not the same.”

LMU represented the apex of Kimble’s basketball career too. The No. 8 overall pick by the Clippers in the 1990 draft, Kimble played just two seasons with them and one with the New York Knicks before finishing out his career in the minor leagues.

Living now in his hometown Philadelphia, he has spent the last decade actively trying to convince an athletic director to give him a chance as a college head coach so that he can run “The System” and give another group of young athletes the same thrill that he had.

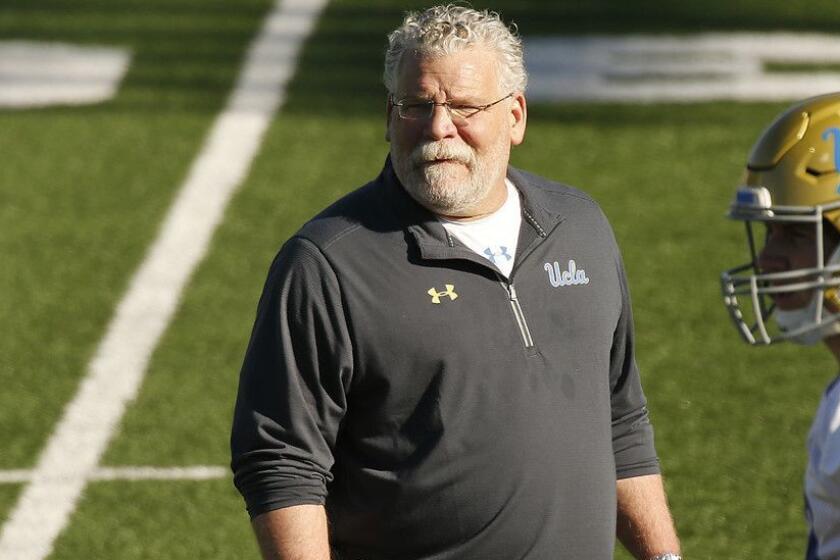

UCLA defensive coordinator Jerry Azzinaro’s new contract calls for him to earn $650,000 in base salary and talent fee in 2020

Kimble, who founded the “44 For Life” foundation in Gathers’ honor, said he has applied for the LMU head coaching job three times without getting an interview.

To Kimble, that’s LMU’s loss, and the losses have certainly mounted for the Lions the last 30 years. The program has not returned to the NCAA tournament.

Fryer came back to his native Southern California and started the Jeff Fryer Basketball Academy in Irvine.

In recent years, he performed shooting clinics with Bryant’s Mamba Academy team featuring Bryant’s daughter, Gianna, and got to know Kobe a little bit.

When Fryer heard of the death of Bryant, Gianna and seven others, he felt hurt by the impact it would have on their shared basketball community in Orange County.

Fryer also thought of Gathers, and, once again, of his own mortality.

“We’re not going to be here, everybody, 10 out of 10 people have to die, right?” Fryer said. “What is going to be your legacy?”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.