Worthy of a second chance? Art Briles coaching high schoolers after sexual assault scandal

BONHAM, Texas — In preparation for the most anticipated home football game here in years, concession stands inside Warrior Stadium were stocked Friday night with 320 hot dogs, 240 hamburgers and 100 pounds of fries.

That was twice as much food as Bonham High math teacher Brandi Holcomb usually orders. And still she worried demand might require a mid-game run to the Wal-Mart across the highway.

There were also four additional police officers walking the field and brand-new credentials printed to handle a media contingent three times the normal size. Gates surrounding the field, always open on game nights, were closed.

Preparations had been three months in the making because of the man on the opposing sideline, whose return to coaching in the United States had taken nearly four years.

For Art Briles, the 63-year-old first-year football coach at Mount Vernon High, the night marked a return to familiar ground — the high school ranks in his home state, where he’d built a reputation scoring points and claiming championships. But leading the Tigers, who compete in the state’s third-smallest classification, was a world away from the elite perch he once held.

During eight seasons as coach at Baylor, Briles transformed the woebegone Bears into conference champions and become one of football’s most innovative, celebrated figures. Then came the fall. Since his firing in 2016 amid a sexual assault scandal that continues to rock the Waco campus, he had been deemed unemployable across North America.

That changed in May, when Mount Vernon made him its coach. When Briles stepped off a school bus inside the stadium grounds Friday, flanked by a state trooper and a school security officer, it was his first game in the U.S. since 2015 and first high school game since 1999.

Walking toward the visitor’s locker room before kickoff, Briles acknowledged “deep emotions running right now.”

Briles has brought to Mount Vernon an all-new coaching staff, his usual wide-open passing attack, and a harsh spotlight.

His hiring sparked debate over whether his second chance was merited, and led to a question that some observers say has yet to yield a satisfactory answer.

After so many others over three years said no, why did Mount Vernon say yes?

::

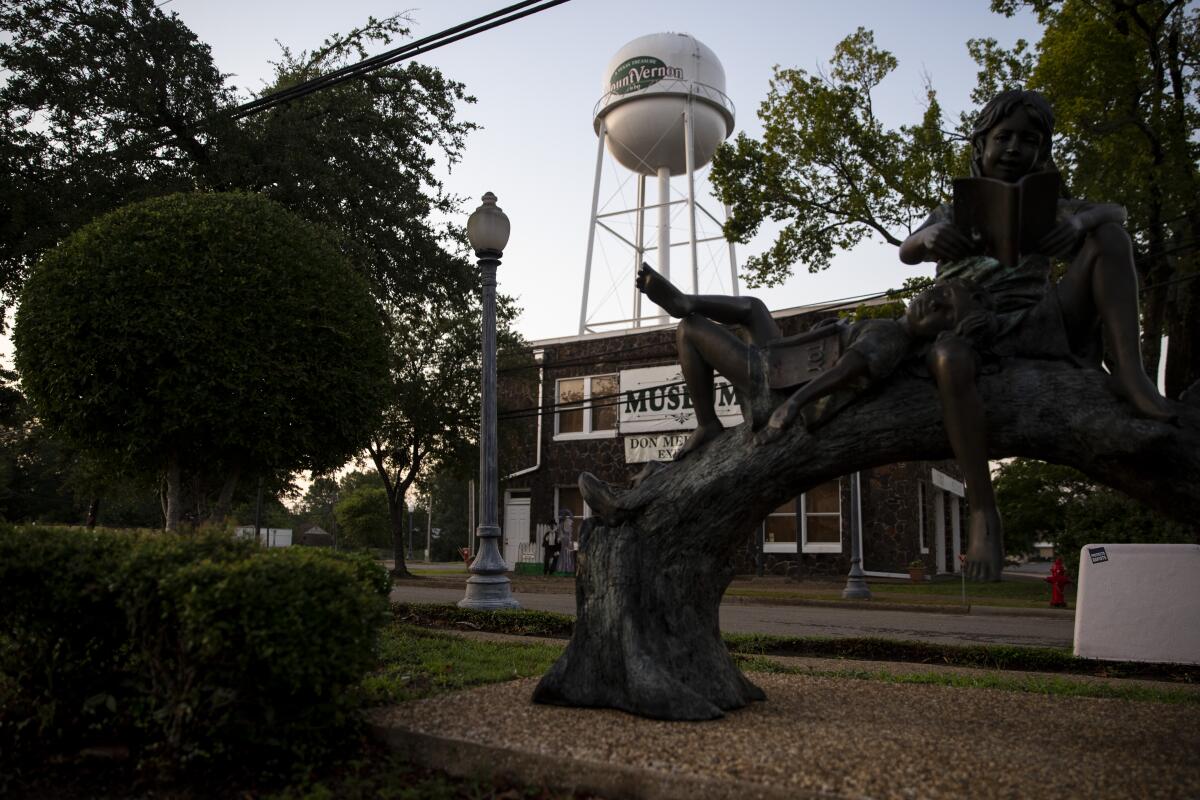

Oaks, elms and white signposts marking historic houses dot the gently rolling hills of northeast Texas.

Don Meredith’s childhood home is on South Kaufman Street in Mount Vernon. The former Dallas Cowboys quarterback and Monday Night Football sidekick to Howard Cosell also has the high school’s football stadium named after him, and a downtown museum exhibit about his life.

A park in the square’s center is bordered by red-brick buildings and a white courthouse. Looming above is the water tower declaring the community a “Texas treasure.”

Jerry Falwell Jr. helped make Donald Trump a winner. Now he and Hugh Freeze are trying to transform Liberty University’s football program.

The only stoplights are a mile south of the square, by the on-ramps to Interstate 30, which shuttles drivers to Dallas 100 miles to the west and the Arkansas border 70 miles east. No one has a straight answer about the population — some say 2,400, others around 2,700.

“We pretty much all know each other,” Mayor Teresia Wims said.

Everybody has heard of the newest resident.

Briles starred while playing for his father at a high school near the state’s panhandle. He was a speedy receiver for Houston before going into coaching in 1979. For the next 37 years he never took a job outside Texas, yet built a national reputation as an offensive genius.

Briles won four Texas state championships at Stephenville High by spreading players the width of the field and challenging defenses to keep track of everyone. College jobs followed: assistant at Texas Tech, coach at Houston and, in 2007, the top job at Baylor, an also-ran program that had reached double-digit victories just once in 108 seasons.

Briles and the Bears won 10 or more games four times in eight years. The world’s largest Baptist university paid him as much as $6 million annually.

“He’s really won everywhere he’s been,” said Dave Campbell, whose eponymous, influential magazine is a self-proclaimed Bible of Texas football. “He knows how to get people open; he knows how to blend great passing attack and a great running attack. Then he winds up with a good offensive line and he’s on his way.”

Weeks before a 2014 season that saw the Bears nearly break into the four-team College Football Playoff, Briles gushed about the university’s new, $266-million riverfront football stadium as a symbol of the school’s changed fortunes.

“They’re going to say, ‘Momma or grandmother, man, look at that place. That place is beautiful. Where is that?’” Briles said. “And she’s going to say, ‘Baylor.’ And then so for the rest of their lives, they’re going to associate Baylor with excellence.”

That was the hope.

::

Recent years have been, in the words of Drayton McLane Jr., the billionaire Texan whose name is carried by the school’s football stadium, “an extremely difficult time for Baylor.”

Sexual assault convictions against two Baylor football players led the university, in 2015, to launch an independent investigation of its responses to Title IX, the federal law requiring gender equity on higher-education campuses. The full report was never made public, but the findings of the investigation, summarized by the school in May 2016, shook the school and set off controversy that has followed Briles since.

The 13-page document depicted a university woefully unprepared to handle Title IX complaints and an athletic department where “choices made by football staff and athletics leadership, in some instances, posed a risk to campus safety and the integrity of the University.” In some cases, the report said, information about sexual violence or dating violence had not been acted upon.

“I did not think it would be a high school team. It’s kind of astounding to me a high school would think he’s right to coach and lead young minds at an even younger age.”

— Brenda Tracy, sexual assault victims advocate

Regents later acknowledged the investigation, by law firm Pepper Hamilton, found 17 women reported sexual or domestic assaults, including four gang rapes, committed by 19 Baylor football players between 2011 and 2016. A 2017 Title IX lawsuit against the university by a Baylor graduate alleged that 31 different Baylor football players committed 52 rapes, including five gang rapes, between 2011 and 2014, and that female students, acting as hostesses for the football program, were used to entice prospective recruits with sex. The case was settled.

Briles was not named in the report, but the scandal cost him and school president Ken Starr their jobs. Athletic director Ian McCaw resigned in the wake of his football coach being fired.

Even with much of the school’s top leadership gone, Brenda Tracy said she was troubled by an attitude that remained within the football program. An advocate for sexual assault survivors, Tracy shared the story of her 1998 rape at Oregon State with Baylor’s football team in July 2016. After she finished, she said an assistant coach, one of several holdovers from Briles’ staff, pulled her aside to say that “there was no problem with football” in Waco.

As part of a settlement at the time of his dismissal, in which Baylor paid Briles $15.1 million, the coach and university acknowledged “serious shortcomings in the response to reports of sexual violence by some student-athletes, including deficiencies in university processes and the delegation of disciplinary responsibilities with the football program.”

Briles has long maintained he did nothing wrong. A 2017 letter written to Briles from Baylor general counsel Christopher Holmes said the university was unaware of any situation where Briles ”personally had contact with anyone who directly reported to you being the victim of sexual assault, or that you directly discouraged the victim of an alleged sexual assault from reporting to law enforcement or [Baylor] University officials.”

Supporters including McLane, a school regent, contend Briles was a scapegoat for systemic problems at Baylor. The school has attempted to burnish its name since 2016, but the results of a two-year NCAA investigation are expected soon and no one knows what to expect. Jane Doe lawsuits against the school have been filed on behalf of 15 women who say they were sexually assaulted while students at Baylor, with some of the assaults attributed to football players.

Tracy said she was disappointed but not surprised that Briles found another opportunity to coach.

“I did not think it would be a high school team,” she added. “It’s kind of astounding to me a high school would think he’s right to coach and lead young minds at an even younger age.”

::

In May, after Mount Vernon’s football coach took a job guiding a rival team, Jason McCullough, the superintendent of schools, and Landon Ramsay, a native son from a prominent local family, were discussing possible replacements when they hit on a radical idea.

McCullough had watched Baylor’s rise while working outside Waco as a school administrator. Ramsay was a Baylor law school graduate who had been a prosecutor in the district attorney’s office in Waco. And his wife, Leigh Anne, was Baylor football’s assistant director of campus recruiting from 2014-16.

She still had Briles’ number, and texted asking whether he would take a phone call from her husband.

“It kind of caught me off-guard,” Briles told reporters in August. “My answer has always been yes. If you ask me, ‘Let’s go to Abilene Junior High tomorrow,’ I’d say, let’s look at it.”

His choices, to that point, were limited.

In 2017, Briles lost a job as an assistant with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League when, only hours after the hiring was announced, the team was engulfed by what team CEO Scott Mitchell termed a “tsunami of negativity.” Team owner Bob Young referred to the hiring as a “large and serious mistake.”

In 2018, the same day it was revealed that Briles had been invited to speak at the American Football Coaches Assn. convention — “Standing Strong/Game Management” was the topic — criticism prompted the organization to quickly repeal the offer.

In February, Southern Mississippi coach Jay Hopson wanted to hire Briles as offensive coordinator but was overruled by bosses, on the basis that the NCAA investigation into Baylor remained active.

“I think there’s going to be a great story here about redemption and forgiveness and restoration. That a community can show a man who was at the top and has fallen way off from where he was and has been shut out.”

— Pepper Puryear, pastor at Mount Vernon’s First Baptist Church

The only job Briles had been able to hold was on football’s fringes, in Florence, Italy, where he coached a low-level pro team last winter.

McCullough called the district’s vetting process “vast,” though he didn’t contact any of the women who have sued Baylor.

“We just felt that looking at all of it in totality was that there was more to it than just what the press was wanting to print, or what the board of regents at Baylor was allowing to come out,” he said. “We thought if we’re really trying to find the best person for the job, from a football standpoint, it’s hard to beat the success that he’s had at every stop he’s made.”

Hours before the high school’s graduation on May 24, the school board unanimously approved a two-year contract for Briles that pays him $82,000 annually, paving the way for his return to the sideline in a state with deep attachments to the high school game.

“It’s the biggest industry in Texas,” McLane said. “It’s not the oil business, like people think.”

Business owners Jeff and Amy Briscoe, whose oldest son is a football-playing eighth grader, say their son has enjoyed the new staff. They add they have full confidence in McCullough. But they lament that the school board didn’t seek community input before the hire and “the division” it has sparked in their community.

“I don’t see how the benefit outweighs the cost,” Amy said.

Gauging overall support for Briles is difficult, residents say, because some people fear speaking out about their reservations. The prevailing sentiment is that the football players deserve strong support.

Said Mayor Wims:“I am still hopeful enough to believe people with opposing viewpoints can be kind to each other.”

Pepper Puryear, pastor at Mount Vernon’s First Baptist Church for 26 years, considers Briles’ second chance a divine opportunity to show Mount Vernon’s best side to a national audience.

Geotagged Twitter data tracking over 100,000 tweets the last month show who will win the 2019 College Football Playoff.

“I think the Lord’s up to something here in this community, about redeeming a man,” Puryear said. “Why in the world would Art Briles be coaching football in Mount Vernon, Texas, if there was not something bigger going on?

“He may need us, we may need him. We may need each other. I think there’s going to be a great story here about redemption and forgiveness and restoration. That a community can show a man who was at the top and has fallen way off from where he was and has been shut out.”

To others, Briles’ presence is a reason for outsiders to believe the worst.

A months-old Yahoo.com headline saying Mount Vernon had “sold its soul” for gridiron success still makes both supporters and cynics wince. Twice this summer, surveillance cameras have caught a pair of yet-to-be-identified vandals placing stickers on downtown businesses reading, “Art Briles Protects Rapists.”

The situation reminds former NBA center Greg Ostertag of a lesson he learned in college at Kansas while playing for Roy Williams.

“We used to have these little sayings before practice,” recalled Ostertag, who moved to Mount Vernon in 2015 and owns a construction company and restaurant with his wife. “One of them was you can’t judge a man until you’ve walked in his shoes for two full months.

“You can’t judge this town based on a hiring.”

::

It was just after 4 p.m. on Friday when Mount Vernon’s football team boarded three buses for an 80-minute drive west toward Bonham and a night of uncertainty.

The Tigers had no idea how they would play or how their coach would be received, and their hosts were bracing as well. Anticipating the potential for protests, officials in Bonham had coordinated security with local law enforcement.

Conflict never materialized. There were no protests. Only a handful of Briles supporters wearing Baylor apparel showed up. In a 6,000-seat stadium that was two-thirds full, Mount Vernon dominated in a 44-16 victory. The Tigers scored from 47 yards out on their fourth play.

A goateed Briles shook hands with opposing coaches at midfield with half a minute remaining. Then, as cameras from a documentary crew followed, he took off on a slow jog toward the locker room.

Fielding questions from reporters after addressing his team, Briles acknowledged he’d felt a little extra pressure.

“I’ve been given an opportunity at Mount Vernon High School in Mount Vernon, Texas, because of some people that believe in me, so I’m extremely grateful and thankful,” he said.

Next week brings another road game, at Farmersville. The first home game is Sept. 13, and locals expect a big night. More media attention is expected. Protests remain a possibility.

“Y’all don’t wanna believe it but I just like to coach football,” Briles said. “That’s all I pay attention to, and that’s all I’ve ever done. People can think and say whatever they want to think and say. I have no control over that.”

Well-wishers formed a long, two-deep receiving line outside the locker room and, with his work done, Briles flashed a broad smile for one of the few times all night.

Before he ducked inside to change, a fan told him supporters had appeared “to come out of the woodwork.”

Later, a few fans hung around the entrance to celebrate as players emerged from the locker room for the bus ride home.

There was no chance to give Briles a final cheer. He slipped out the back door, into a warm Texas night.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.