Bob Bradley and Bruce Arena are MLS foes, but always friends

FOXBOROUGH, Mass. — Imagine being a fly on the wall when George Halas and Vince Lombardi got together to reinvent football more than half a century ago. Or having a chance to listen in when Phil Jackson taught Michael Jordan the triangle offense in the late 1980s, changing the NBA forever.

That’s what summer vacations with a young Bruce Arena and an even younger Bob Bradley must have been like.

A generation ago, soccer was little more than a cult sport in the U.S. The men’s national team hadn’t won a World Cup game in more than 50 years and professional leagues were something they had in Europe and South America, not here. So when Arena and Bradley would gather at a sprawling beach house on the North Carolina’s Outer Banks in the early 1990s to dream and scheme and cultivate the ideas that would give flower to the two most successful coaching careers in American soccer history, it was the closest thing to a graduate seminar in the sport as you could find in this country.

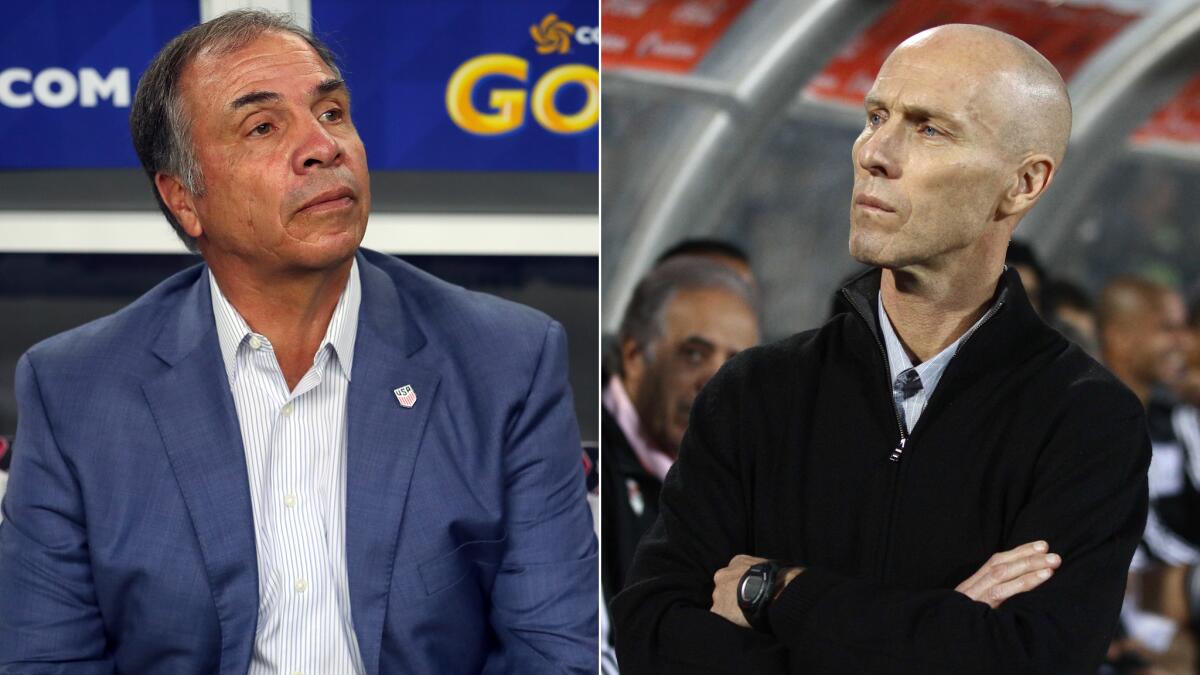

Arena, 67, and Bradley, 61, the only MLS coaches born in the 1950s, met at Gillette Stadium on Saturday when they faced off on a soccer field for the first time in 21 years, with Bradley leading the Los Angeles Football Club, the best team in MLS, to a 2-0 win over Arena’s New England Revolution, which had been the league’s hottest team.

“They come from a different time, a different era,” said Michael Bradley, Bob’s son and a national team player under both coaches who listened intently, even as a boy, when the men debated the finer points of the game into the night. “There wasn’t soccer on TV every second of the day. You couldn’t find every game from around the world on the Internet.

LAFC outshoots the Revolution, 22-10, en route to a 2-0 victory that breaks Bruce Arena’s undefeated run as New England’s coach.

“What they quickly recognized in each other was a love for the game and a strong competitive desire to learn and to grow and to improve in what they were doing.”

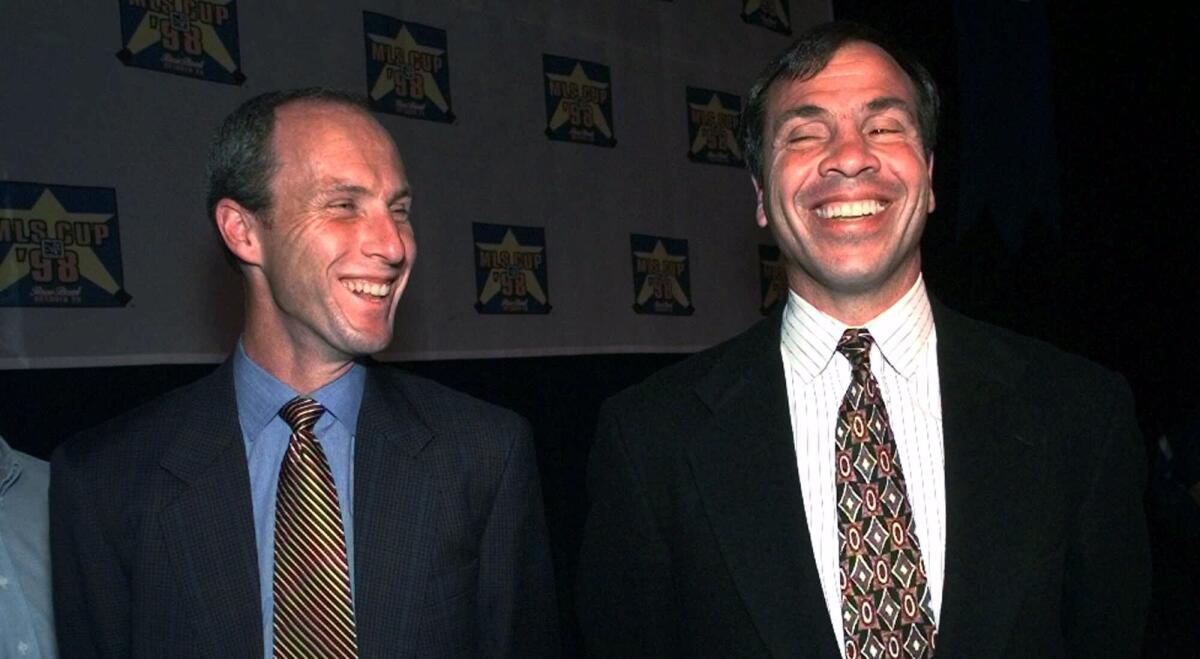

It was a partnership that became a friendship, one that has endured for nearly four decades. They coached together in college, in MLS and with the U.S. Olympic team, combining to win 124 games with the national team and 364 in MLS, reaching three World Cups and capturing six MLS titles.

Arena, who won three league championships with the Galaxy and now has New England rising in the playoff race, is the only coach to take the U.S. men to two World Cups, reaching the quarterfinals in 2002. Bradley managed national teams in Egypt and the U.S., club teams in MLS, Norway and France and is the only American to have coached in the English Premier League.

“We’re friends,” Bradley said. “We’ve worked together. We’ve been rivals [and] competed against each other.

“I challenge him in certain ways, he’ll always challenge me. That part hasn’t changed.”

Their debates often ended with someone claiming victory, but there was never a loser.

“The best two guys in America to be involved in the national team are Bob and I. That’s a fact. If I had to hire a coach, I’d hire Bob,” Arena said on the eve of Saturday’s game.

“How rewarding this is for us to have this opportunity this many years later.”

:::

Like many kids growing up on Long Island in the 1950s and ‘60s, Arena dreamed of playing baseball for the New York Yankees. He honed his arm by throwing thousands of pitches against a brick wall across the street from his home and taught himself to switch-hit by emulating his idol, Mickey Mantle.

“Greatest athlete I ever saw,” Arena fawned.

As a child, Arena was undersized and overfed — “like a bowling ball almost,” his brother Mike remembered in a Sports Illustrated profile — so he was shuffled off to the wrestling mat and to midfield for the lacrosse team.

Although his immigrant grandfather kept a poster of the Italian national team on a wall of his Brooklyn deli, Arena thought soccer was an odd sport — until the starting goalkeeper at his high school was suspended for hitting an opponent. Arena volunteered to take his place. It proved to be a life-altering decision.

Arena went on to play professionally in the short-lived American Soccer League and make one appearance for the national team. He might have played more for the U.S. team, but the junior high where he taught wouldn’t give him the time off; it was a different era.

The U.S. women’s soccer team negotiated for control of the rights to their names and likenesses in 2015, a move that followed the NFL players’ union blueprint.

Arena eventually made his way to the University of Virginia, where he coached soccer and lacrosse. The competitive seasons didn’t overlap, but offseason training did, so when a friend recommended a tightly wound 22-year-old graduate student from Ohio University for what Arena called an internship, he gave the job to Bob Bradley.

“Probably the only intern I ever had,” Arena said last week.

Bradley was certainly the best one he ever had.

“They were good years,” Bradley remembered. “Seeing the way he ran the program and the things he did at Virginia, that was excellent.”

Bradley grew up 70 miles and six years apart from Arena. And, like his mentor’s, Bradley’s childhood was dominated by sports. The difference: soccer was always the main goal, not a consolation prize.

“There was just this pull,” said Bradley’s younger brother, Jeff, a former soccer and baseball writer who is director of communications for the MLS team in Toronto. Another brother, Scott, played nine seasons in the majors.

“Even though he played pee-wee football and baseball and all the other sports, he knew that when he got to high school he wanted to play soccer,” Jeff Bradley said. “People laughed at him.”

Bob Bradley got the last laugh, playing four years for his high school team and winning a New Jersey state title before going on to Princeton and earning a coveted spot in the executive training program at Procter & Gamble.

“Bob hated it so much,” Jeff Bradley said of his brother’s time in the corporate world. “He still wanted to be playing, but there were no opportunities for American players back then.”

Bradley did the next best thing: He became a coach. And it wouldn’t be long before he found a kindred spirit in Arena.

“Bob was driven, motivated, bright and wanted to be successful. And knew that he wanted to get into coaching,” Arena said. “It’s the same thing with me. I had no interest in anything academically. I knew I was going to be a head coach one day.”

:::

Another thing you hope you know as a coach is when it’s over. Bradley didn’t think his career was over when he failed, against long odds, in an 11-game trial at Swansea City in 2016. So, eight months later, he signed with LAFC, proving himself right by winning more games in his first two seasons than all but one other MLS coach.

Arena’s coaching career also seemed to end prematurely when a pair of freak goals on a rain-sodden field in Trinidad derailed his efforts to quality the U.S. for another World Cup in the fall of 2017. He resigned, wrote a book, agreed to do some TV work, and waited impatiently for the phone to ring.

He thought he had a job in Columbus, but that fell through. He also talked to the Galaxy and offered to walk on to Bradley’s staff at LAFC. Then, in early May, the Revolution called.

The team was 2-8-2 and last in the Eastern Conference and needed someone to turn it around. Arena had done that twice with the national team and most spectacularly with the Galaxy, taking over a team well on the way to a third straight losing season and guiding it to eight consecutive playoff appearances and three MLS titles.

Would he take a shot at doing that again?

“I really had my doubts,” he said. “But at the end of the day, this is what I do.”

Not long after Arena was hired, Kaitlin Gangl Alden, the Revolution’s communications director, got a call.

“If Bruce isn’t making fun of you,” a former Arena associate told her, “something’s wrong.”

During his four stops in MLS and two stints with the national team, Arena had become part Alex Ferguson and part Lenny Bruce; a brilliant coach and manager of personalities who uses sarcasm and caustic humor to draw those he likes near — and keep those he loathes away.

Bradley’s public persona is as serious as a root canal. Questions aren’t answered with punch lines or sound-bite brevity, but with depth and detail — or scorn if you can’t keep up.

“They’re different guys personality-wise. [But] in terms of being coaches and managers, they have tons of similarities,” said Kenny Arena, 38, who coached on his dad’s staff with the Galaxy and the national team and is now an assistant under Bradley, who used to baby sit him.

They’re different in other ways too. Bradley has the build, demeanor and scowl of a drill sergeant. Arena, larger and softer, has a temper that can flare, but is often playful.

Lionel Messi has been suspended for three months because of accusations of corruption he made at the latest Copa América.

“When you call Bob, you’ve got to be ready for him. You’ve got to be on your toes,” said Dave Sarachan, a former MLS manager who assisted Arena with both the Galaxy and national team, then succeeded him as the national team coach.

Sarachan, who replaced Bradley on Arena’s staffs at Virginia and with D.C. United, also followed him to the North Carolina beach house for a week or two each summer. There was a certain rigidity to those family vacations: Arena and his wife, Phyllis, paid the rent, Bradley and Sarachan bought the groceries and did the cooking.

No one came for the food though.

“It was always going to end up being those conversations,” said Sarachan, who coaches a USL team in Cary, N.C. “If I came up with an idea, it could get challenged by Bruce. Then Bob would overhear that and he’d challenge Bruce.”

When things got too deep or heated, Arena would go off to buy doughnuts for the kids, taking desertion to be the better part of valor.

Those vacations made everyone — even the children — better at the sport.

Sarachan’s son Ian who, like Kenny Arena and Michael Bradley, attended those summer retreats as a child, is a coach at Creighton.

“There’s ways you learn the game,” Dave Sarachan said. “You can learn it through textbooks. You can learn it through school. You can learn it at different levels or being an assistant or even being a head coach.

“For me, the greatest classrooms were the summer evenings, the interaction with really great minds of the game.”