‘Peace Village,’ a fake city just outside the DMZ, serves as metaphor for North Korean athletes at the Olympics

Reporting from Pyeongchang, South Korea — From their hilltop checkpoint, the soldiers who guard South Korea’s border can see for miles across the Demilitarized Zone, to a small city in the distance on the north side.

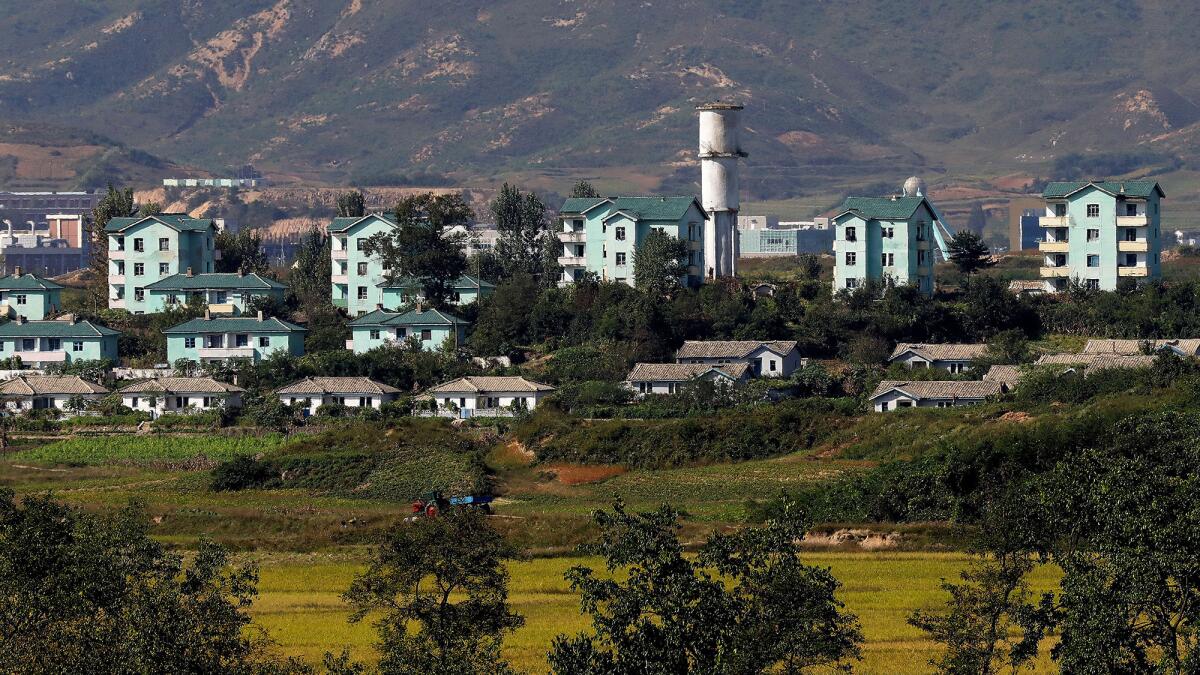

This tidy collection of high-rises and low-slung buildings is surrounded by agricultural fields. North Koreans call the place Kijong-dong, or Peace Village.

The multinational troops on the South Korean side have a different name for it.

Propaganda Village.

South Korea has long contended that Kijong-dong is a façade manned by the North Korean military.

Some of the buildings have their windows painted on, said Cmdr. Robert Watt of the combined Southern forces. Other tall structures appear to be shells; when night falls, light shines brightly in upper windows but is dim closer to the ground, suggesting there are no floors or walls inside.

Music blares from loudspeakers, drifting eerily across the winter-browned countryside. A towering flagpole rises high above.

North Korea created all this, Watt said, in hopes of persuading South Koreans to defect, as in: What a nice city. I’d like to live there.

Now that the 2018 Winter Olympics are in full swing about 100 miles away, the mystery surrounding Kijong-dong serves as a metaphor for the North Korean athletes who have come to Pyeongchang.

Twenty-two of them are competing in women’s hockey, figure skating and other sports. Critics have dismissed their presence as a publicity stunt by the North, but others have hoped they might offer a glimpse into a country the world knows so little about.

::

In the six decades since the Korean War reached a jittery cease-fire, the North has kept itself largely shuttered.

Recent sparring between leader Kim Jong Un and President Trump, the men trading threats of nuclear war, has only heightened curiosity about the reclusive nation.

“When most people think of North Korea, we think of Kim Jong Un, rockets, missile launches,” said Peter Kim, an American-born assistant professor at Kookmin University in Seoul. “To put our hands around other things beyond what we see in the media, it’s really next to impossible.”

No one expected North Korea to participate in the Games, not until Kim Jong Un made conciliatory remarks toward South Korea in a New Year’s Day speech. Hurried negotiations led to a deal by which the North sent a small contingent of athletes, coaches and officials.

The agreement also included a cheering squad, which could be seen entering the country in a convoy of buses moving slowly across the Tong-il Bridge.

Though skeptics called it a ploy by Kim to appear statesmanlike and engaged with the international community, the arrival of the North Korean squad generated a worldwide buzz.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that, as long as North Korea is here, the whole international community is watching to see what clues it might pick up,” Peter Kim said.

A week into the Games, those clues have been limited to dribs and drabs.

The official Olympics website, which includes information on every competitor, is an example. Many of the entries include brief personal histories, favorite quotes and lists of hobbies such as going to the movies, spending time with friends, playing computer games.

The North Koreans tend to offer few, if any, details. Hobbies are often described in a single word. Music. Reading. Sports.

The PRK team — its Olympic designation, for People’s Republic of Korea — has been pleasant and gracious but reticent to speak publicly, often hurrying through the mixed zone where athletes face the media after competitions. When women’s hockey player and torchbearer Jong Su Hyon attended a news conference early on, reporters were given an unusual warning.

“Please note that we may decline any of the questions that might make the athletes uncomfortable such as ones about politics or doping,” the moderator said.

In the days that followed, PRK team members stuck to a common theme, speaking in generalities if not platitudes.

“First of all, there have been no inconveniences whatsoever to life in the South area,” pairs figure skater Kim Ju Sik said. “We could really feel the power and the energy of the Korean people.”

Reporters haven’t been the only ones hoping to learn more about North Korea through its athletes. As part of the Olympics deal, South Korea agreed to add 12 players from the North to its women’s hockey team.

The South Korean players said that getting to know their new teammates was a gradual process.

“Part of that is the separation that’s built into it,” Randi Heesoo Griffin said.

The North Koreans slept in separate dorms and took separate buses. Language was an issue because they did not always understand English terms, such as “line change” and “faceoff,” that South Koreans use among themselves to communicate about the sport.

The locker room and team meals offered the best chance for small talk.

“When we sit in the dining hall and we have conversations, it’s pretty much everyday stuff, like talking about who has a boyfriend,” Griffin said. “So they’re just people.”

At times like these, the team’s coach felt encouraged.

“When you see them sitting at a table, you can’t tell who’s from the North and who’s from the South,” said Sarah Murray, who is Canadian. “They’re mixed and they’re laughing and they’re just girls.”

The team was together for only a couple of weeks, losing all three of its games and failing to advance to the medal round.

It seems that individual sports have offered less interaction.

“I haven’t made friends with any other skiers,” Kim Ryon-Hyang of North Korea said after the slalom competition. “But I hope to in the future.”

::

At the start of the Pyeongchang Games, Kim Jong Un sent his younger sister to attend the opening ceremony, where athletes from the North and South marched together behind a white unification flag that bore the pale-blue silhouette of the Korean Peninsula.

Kim Yo Jong then met with South Korean President Moon Jae-in and, on behalf of her brother, invited him to a summit.

It remains to be seen if the countries will hold their first top-level talks in a decade. For all their reticence to speak politically, the North Korean athletes seem to be pushing the idea.

“I am very hopeful the two countries will unite as one in the future,” Kim Ryon Hyang said.

If the notion of the Olympics as a gateway to permanent peace on the peninsula has been met with skepticism in South Korea and other parts of the world, it is probably because the nations have a long history of tense relations and not much meaningful communication.

Which leads back to a story Watt tells about Kijong-dong.

In the 1980s, South Korean officials erected a 330-foot flagpole along that stretch of the DMZ, in a farming community on their side, he said. They flew a large national flag that outdid the one in Kijong-dong, which at the time stood about 164 feet high.

Within days, the North Koreans extended their pole to 560 feet.

Follow @LAtimesWharton on Twitter

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.