Rio is a contrast in new and old, as many residents see more harm than good in hosting the Games

Reporting from Rio de Janeiro — A gleaming sports mecca has appeared on the shores of Rio de Janeiro, a cluster of stadiums and arenas with brightly colored facades and domed white roofs.

The main Olympic Park will serve as center stage for athletes from around the world who have arrived here for the Summer Games.

But these brand-new venues cost billions of dollars, a hefty price for a city — and a country — that has suffered through an economic freefall over the last few years.

Just to the east of the park, dozens of people sit in a run-down lobby at Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital, waiting to see a doctor. Dozens more stand outside the emergency room, eager to hear about loved ones.

“No, I don’t think we need that at all,” Almir Duarte, a 57-year-old resident says of the mega-sports competition that will begin with the opening ceremony on Friday. “The government needs to invest more in healthcare.”

The public system tended to Duarte when he first broke his leg, but then recommended further treatment at a private clinic. His salary as a construction worker barely allowed for the additional expense.

“We need a basic level of public services before they put on an event like that for foreigners,” he said.

His complaint raises an all-too-familiar concern when it comes to the Olympics and cities that devote tens of billions of dollars for a sporting event that will be gone after 17 days.

All this week, trucks have rumbled through Olympic Park as workers put the finishing touches on the expansive plaza.

The team handball venue has an elaborate exterior fashioned to look like countless match sticks stacked one on top of each other. The velodrome has a gleaming wooden track.

“It’s fast in the corners, with a long straight, maybe a little too long for the racing,” German cyclist Roger Kluge said. “But it’s nice; a beautiful, big stadium, and it looks big on the inside.”

When the International Olympic Committee chose Rio as a host in 2009, Brazil’s economy was booming.

Over the last few years, investigators uncovered a multibillion-dollar corruption scheme implicating much of Brazil’s political and business elite. That — and a fall in prices for Brazil’s commodities — sparked a national crisis that led to the controversial removal of elected President Dilma Rousseff pending an August impeachment trial.

As the country slipped into its worst recession in decades, the budget for the Games continued to grow significantly, as often happens with host cities.

“Political parties can change and the political and economic situation can change,” Carlos Arthur Nuzman, president of the Rio 2016 organizing committee, said recently. “It is not easy, but we are doing it.”

IOC member Alex Gilady of Israel put it another way: “The crisis has nothing to do with the Games.”

The organizing committee recently announced plans to slash as much as $500 million from its $1.9-billion budget. Grandstands at some venues were reduced in size, and Rio 2016 brought aboard fewer of the volunteers who help keep any Games running.

Those operating expenses represent only a small portion of the money required to run such a massive event. A far greater expense is divided into two parts.

The Brazilians have spent an estimated $2.1 billion on arenas and other athletic facilities, according to a municipal government spokeswoman.

An additional $7.5 billion has gone into civic works and transportation, with much of that paying for a new metro line completed just days before the opening ceremony.

A recent poll performed by the respected Datafolha agency said that 51% of Brazilians surveyed had “no interest” in the Games, and 33% said they had “a little interest.”

Moreover, 63% of Brazilians said they believed the Games would bring “more harm than benefit.”

As recently as two years ago, there was similar debate about the estimated $51 billion that Russia spent on the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi and its surrounding infrastructure.

Olympic leaders have long insisted that they should not be held responsible if host cities use their event as an excuse to build new roads, railways and hotels.

At the same time, IOC members see such infrastructure improvements as proof that the Games can be of benefit.

The cluster of towers that have been constructed for the athletes village in Rio, for instance, will be converted to luxury apartments after this summer.

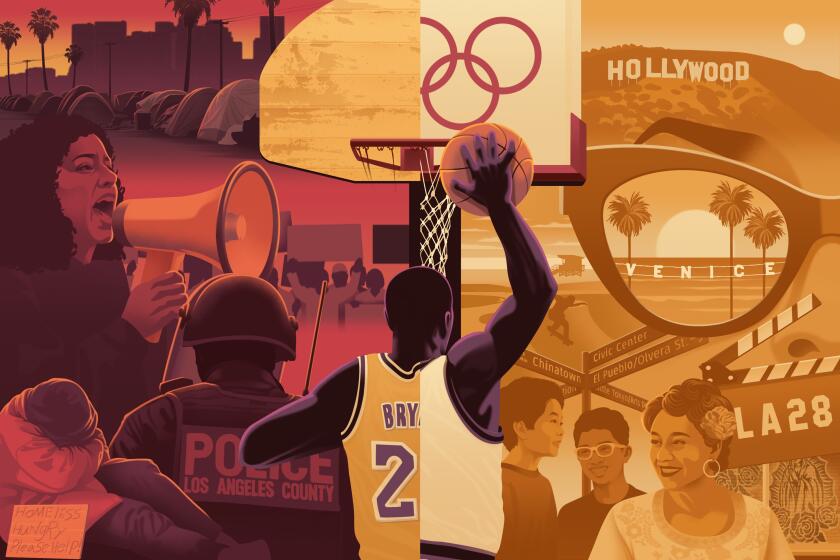

“The capital investments stay and get used for very long times,” said Anita DeFrantz, an IOC member from Los Angeles. “And the people will have this wonderful experience … that will stay with them for a long time.”

The long-term value of sports arenas is more questionable. Sochi’s grand Olympic Park has gone mostly unused over the last two years and is reportedly falling into disrepair.

At the Souza Aguiar hospital, 17-year-old Williana Soares waits for her sister whose recent appendix removal led to complications. She says hospital lines are a problem, and so is crime.

“My God, the situation is horrible where I live,” she says.

Brazil’s crisis has hit Rio harder than most states, leading officials to declare a state of emergency and to a strike by unpaid police officers.

In June, a drug-trafficking suspect known as “Fat Family” was being treated here under police guard. When armed men tried to free him, a bystander was killed in the crossfire.

“That’s a pretty obvious problem,” Soares says. “How are we not even safe at the hospital?”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

MORE ON 2016 OLYMPICS

Olympics are expected to bring ratings gold to NBC despite problems in Rio

Rio tries to balance traffic and geography as Olympic Games ready to start

Star gymnast Kohei Uchimura racks up a $5,000 phone bill playing ‘Pokemon Go’ before Olympics

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.