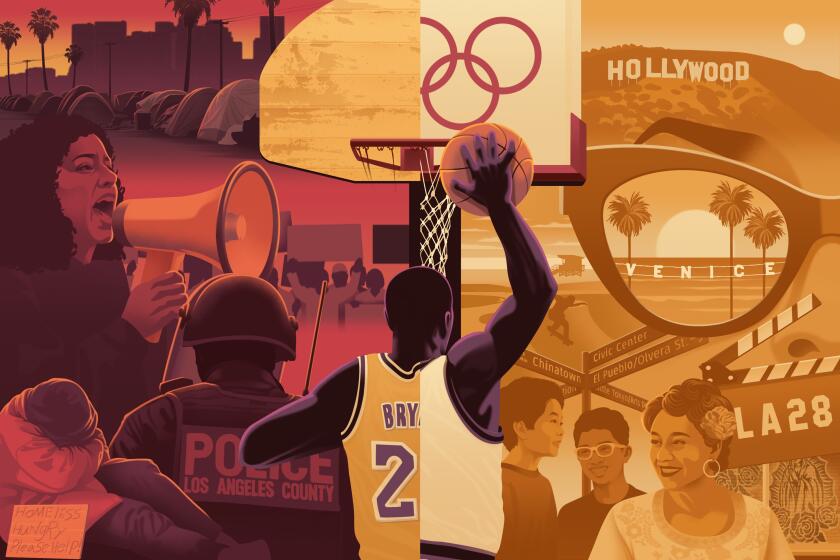

Commentary: Time will be the ultimate judge on if L.A. made a good deal to take 2028 Olympics

The mood was nearly giddy among Olympic athletes and city officials who gathered at StubHub Center on Monday.

Local bid leaders had called a news conference to formally announce a deal with the International Olympic Committee that would pave the way for bringing the 2028 Summer Games to Southern California.

“This is a big win for Los Angeles,” bid chairman Casey Wasserman said.

But as terms of the agreement emerged, City Council President Herb Wesson injected a dose of reality amid the excited speeches and congratulations.

“Nothing is perfect,” Wesson said. “So we are not going to please everyone.”

It probably will be more than a decade before anyone knows for certain if L.A. struck a good bargain with the IOC.

Bid leaders had sought concessions for taking 2028 and letting rival Paris go first in 2024. There had been speculation about Olympic leaders handing over a lump sum of money — through a bigger slice of their broadcast and sponsorship revenues — in exchange for L.A. waiting around another four years.

Instead, the host city contract made public Monday suggests a more nuanced arrangement.

“There is so much that could happen … and not happen,” said Jules Boykoff, a political science professor at Pacific University in Oregon who has studied the business of the Olympic movement.

The deal includes some certainties.

Olympic leaders agreed to waive various payments that should save L.A. tens of millions of dollars. The IOC will also hand over a $180-million advance over the next five years to pay for organizing committee operations and help fund youth sports programs citywide.

But from the start, it seemed unlikely that the IOC would give away too much cash, if only because it could not afford to set that kind of precedent with subsequent bidders.

Wasserman, Mayor Eric Garcetti and Gene Sykes, the bid committee’s chief executive, instead focused on creating opportunities for potential future revenue.

The sponsorship arrangement they negotiated could result in L.A. receiving an IOC contribution of $2 billion or more — a substantial jump from the estimated $1.7 billion that Paris will get in 2024.

And L.A. persuaded the IOC to waive its usual 20% of any surplus generated by the Games.

That could prove valuable with a 2028 plan that seeks to save billions in construction costs by using existing venues such as the Coliseum, Pauley Pavilion and Staples Center.

If organizers can generate a surplus of $500 million or so, as they have quietly predicted, the extra percentage from the IOC would total $100 million.

“I think Garcetti, Wasserman and Sykes have, from the very beginning, managed this thing really well,” said Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College in Massachusetts who has been a critic of past bids. “They are just really talented and have played their cards right.”

Zimbalist also believes L.A. found a way to emerge victorious from a situation in which it might have lost to Paris for the 2024 Games.

The French capital represented a sentimental choice after two close losses in recent bidding cycles. It offered an additional, compelling narrative because 2024 will mark 100 years since it lasted hosted the Games in 1924.

The economist offered one more reason L.A. might have fallen short: “Donald Trump.”

Boykoff views the situation from a different perspective, citing a recent IOC financial report that listed $3.2 billion in assets versus $1.2 billion in liabilities.

“There’s plenty of money floating around,” he said. “My guess is L.A. could have squeezed a little bit more.”

The political science professor also was troubled by the speed with which L.A. and Olympic leaders made their deal.

It was only last month that IOC members voted to approve the dual-award scenario.

L.A. must still have its agreement approved by city and state legislators, who previously voted to provide financial backstops for 2024, but there was no time for public forums on switching to 2028.

Opponents of the L.A. bid have questioned why so much time and effort – if not money – is being devoted to a sporting event while the city faces widespread problems such as homelessness.

“If I were a resident of Los Angeles,” Boykoff said, “I would want another chance to talk about all this.”

Such concerns could be eased if, like the 1984 Los Angeles Games, the 2028 version finishes with a large surplus that could be spent on public programs for years afterward.

That is what Garcetti, Wasserman and Sykes envisioned as they made their deal with the IOC.

Whether or not they will succeed remains to be seen.

Follow @LAtimesWharton on Twitter

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.