There’s a catch to former 49ers great Dwight Clark and his battle with ALS

Reporting from capitola, calif. — A cruel twist — and there have been so many — is it started with the hands.

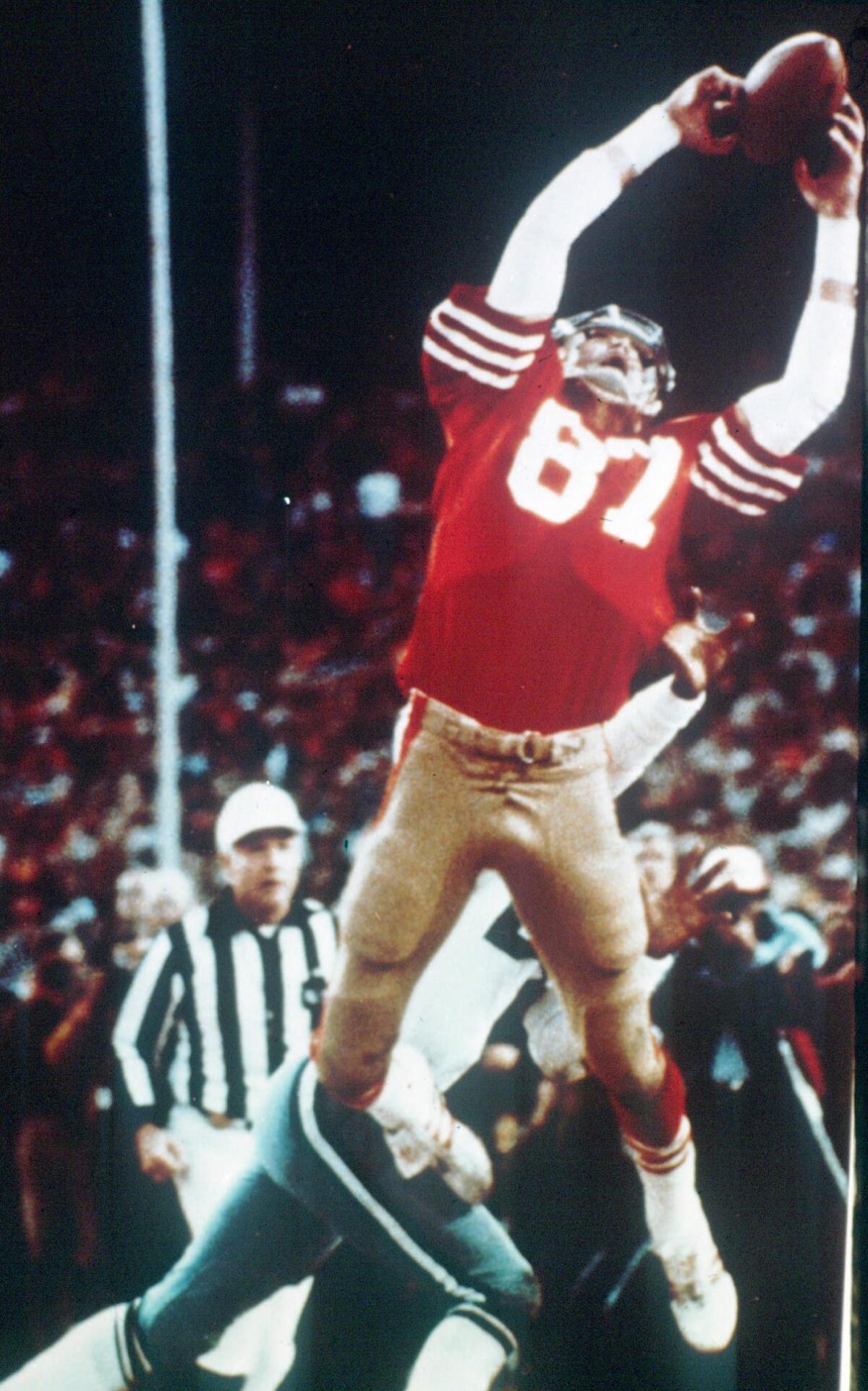

Dwight Clark’s spectacular hands were failing, the ones that famously launched the dynasty of the San Francisco 49ers with “The Catch,” his six-yard grab in the back of the end zone with 51 seconds left against the Dallas Cowboys in the NFC Championship game on Jan. 10, 1982.

It was less than three years ago that Clark’s left hand grew alarmingly weak.

“I couldn’t tear open a package of sugar all of a sudden,” he said. “Then it kept getting weaker.”

Clark, 61, told the story Tuesday at a beach-side restaurant in the town where he lives. He invited eight sports reporters to lunch, writers who covered him over the years, to swap stories and speak in depth about his battle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The condition, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, attacks nerve cells.

He can go short distances with a walker now, but mostly uses a motorized wheelchair. He still has his dashing good looks and easy smile, but he’s much thinner than he was as a player in the 1980s, when he and quarterback Joe Montana were the toast of San Francisco.

The 6-foot-4 Clark was 242 pounds when he was diagnosed in September, 2015. He dipped all the way to 155 before bouncing up a bit.

“I was going to die because I was losing too much weight,” he said. “So I got a feeding tube and now I’m at 167. They’re trying to get me to 190.”

It’s a terminal disease, and Clark is doing everything he can to slow its progress. With the help of former 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo, who seemingly spends every waking hour trying to help his onetime star receiver fight this beast, Clark is at the cutting edge in terms of treatment.

Clark went to Japan so he could be treated with the drug Radicava before it was widely available here. He brought a huge amount of that back with him and is encouraged with the way it has slowed the progress of the disease. He has been to Boston for treatments. He’s excited about the stem-cell research being done in Israel.

“There’s people coming up with stuff all the time,” said Clark, who turned 61 on Monday, two days before the 36th anniversary of The Catch. “Somebody may stumble onto something. I don’t think it will be in time for me to use it.”

Not surprisingly, Clark has battled depression and anger about his condition. His body has betrayed him, and the connection to football and head injuries is undeniable. The staggering costs of treatment are offset by what he’s gotten from the NFL settlement, although there are plenty of players still fighting for the same.

“There are four things that they really won’t even fight you on — ALS, Parkinson’s, dementia, and Alzheimer’s,” he said. “I had been diagnosed before the settlement was finally done, on Jan. 7, 2017, so I just had to send mine in. But if you’re diagnosed after, you have to be diagnosed by someone that’s selected by the league to test you.”

Three concussions stand out in his mind. He got hit in Green Bay and had no idea where he was. He took another at the Meadowlands in New Jersey and started walking to the wrong bench. And he took a shot to the side of the head at Candlestick Park and temporarily lost vision in his left eye.

Clark has a lifetime of good memories about football too. He cherishes the friendships he made, and now has lunches in Capitola every Tuesday with teammates from those days. Montana has been down. Ronnie Lott stops by multiple times a month. Harris Barton, Roger Craig, Jerry Rice, they’re all regular visitors. The Tuesday sessions were the idea of former 49ers media relations director Kirk Reynolds, who accompanies Clark to them along with fellow front-office alumnus Fred Formosa.

Montana called Clark “the consummate receiver.”

“He’s not the guy who’s going to get by you every time, but he’ll get by you if you ask him to,” the Hall of Fame quarterback said by phone. “He’ll do everything you want him to. He’ll block downfield. He’ll come in tight and be a small tight end. He never even questioned it.

“One of the things about him is that when you were in trouble, he was always coming to find you. He didn’t care what was happening. He knew that when the quarterback was flushed, or there’s stress on him, you’re moving and he was coming to find you to help if he can.”

Now, all those old teammates are coming to find Clark, to help in any way they can.

“You start seeing the guys around you like [receiver] Freddie Solomon, who passed away a few years ago,” Montana said. “Life’s too short to have anything come between you. Because you just don’t know, especially with this stupid game we played. Nobody really knows what’s going on, where and how. I don’t take anything for granted anymore.”

Quickly exhausted, Clark spends much of his days napping and watching TV. But Tuesday was a good day. He spent 2½ hours telling stories and laughing about his time at Clemson and the 49ers, and later as a team executive in San Francisco and Cleveland.

Clark was so popular that a San Francisco developer paid him $15,000 a year — half as much as he got from the 49ers — to live in a luxurious condominium in the heart of the city. He was undeniably “The Catch.”

“He had done this in L.A. with movie stars or whatever,” Clark said. “But he’s paying me 15 grand to live at 101 Lombard. I’m single, and the place had three levels. It was one-bedroom, the bed was at the bottom. The middle floor was the family room, kitchen and dining room. And the top was a roof that looked out over the Bay Bridge. It was unbelievable.”

That was 1982, when the players went on strike — a stretch Clark called “the most incredible 57 days of my life.”

“So, we play two games and then go on strike,” he said. “And I’ve got that place, money, notoriety, and a Super Bowl ring. It was like being Huey Lewis.”

Then there was the time right before the first Super Bowl parade, when a furrier in Union Square gave Clark and Montana fur coats for posing for an ad.

“So Joe and I picked out freaking fur coats,” he said, shaking his head in embarrassment. “It was the only time I ever wore it. After I saw myself in it … those were some terrible pictures. I saw myself up at the podium in that fur coat.”

Everyone wanted a piece of Clark.

“People were coming up and tearing the fur out of it when we were on the trolley car,” he said with a laugh.

In truth, even though he grew up in North Carolina and is a country boy at heart, Clark never took to hunting.

“I can’t even think about killing an animal now,” he said. “I went hunting one time. I killed a squirrel and it made me want to throw up. I’m not made for killing.”

Clark is all about living. All his energy is focused on that. Often, he feels overwhelmed, something he disclosed at the end of an otherwise upbeat afternoon of reminiscing.

“I’ll say to my wife, ‘I just can’t … believe I got this disease. Give me something I can fight,’ ” he said. “But you just can’t do it. People get sick. You get a chance to fight. I’m still fighting it, but I don’t have the gloves on.”

He’s in frequent contact with Steve Gleason, the former New Orleans Saints player fighting the same disease. Clark watched the first half of the award-winning documentary “Gleason,” but couldn’t bring himself to finish it.

“The future is so scary,” Clark said. “I can’t imagine being totally paralyzed. I keep trying to reenact it — just lay there, and think, ‘I can’t get up.’ But I can’t do it for very long. It freaks me out.”

He has ordered a microphone and software to record his voice, so he can use a computer to speak when he no longer can.

Even the cuss words?

“Oh, hell, yes,” he said.

In so many ways, he’s still the same Dwight Clark.

“This [disease] will definitely get your attention,” he said. “I’m just trying to do everything I can.”

Follow Sam Farmer on Twitter @LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.