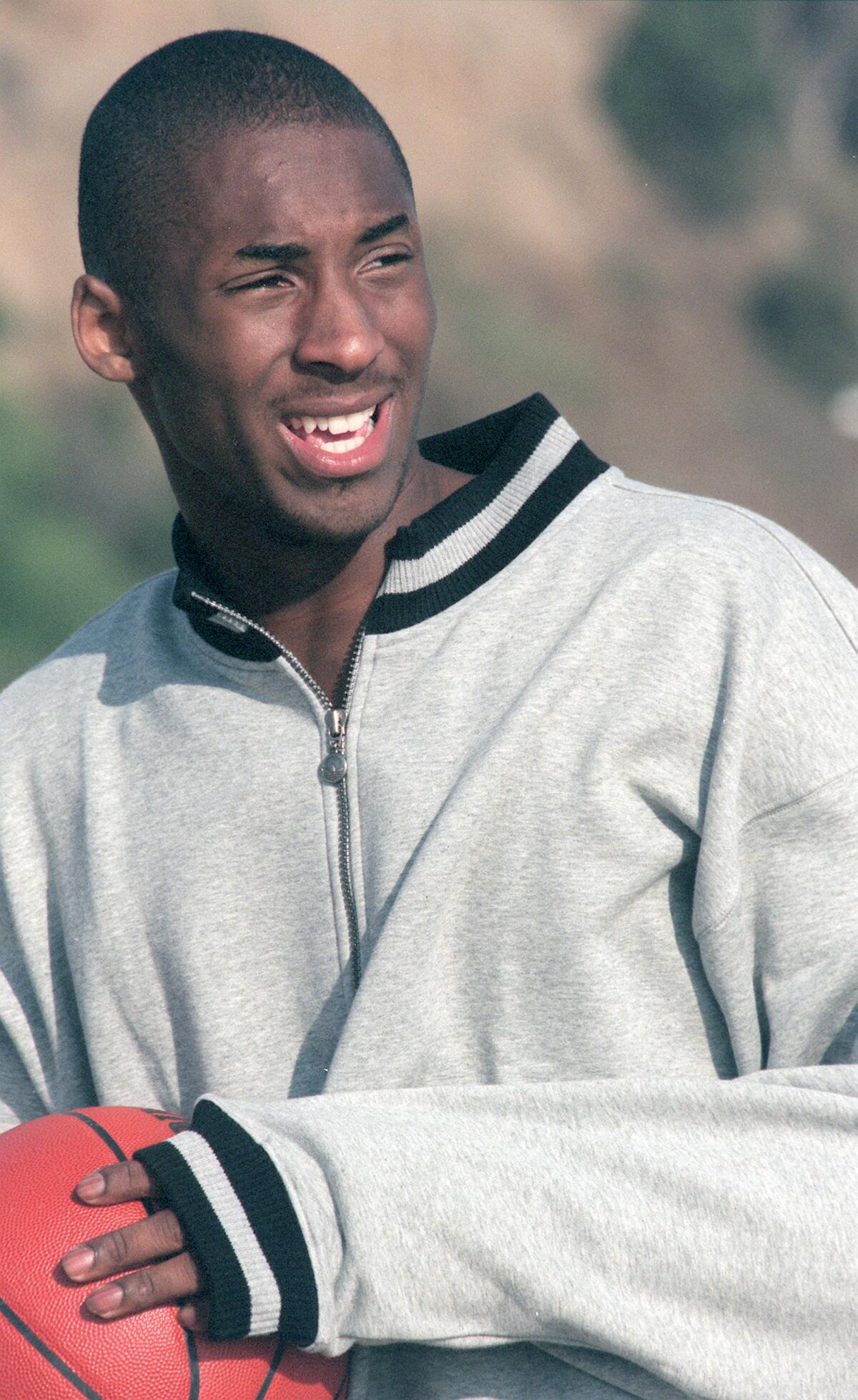

Column: Kobe Bryant humbly begins his jump from preps to pros

Behind him, clouds brushed the tops of the Santa Monica Mountains and the sun gilded the ocean, but Kobe Bryant was oblivious to the stunning backdrop at Will Rogers State Beach.

For more than two hours Bryant, the high school sensation who has yet to play a game with the Lakers but already has an Adidas contract and a Screen Actors Guild card, concentrated on soaring skyward for layup after layup while a photographer snapped images for a poster.

Eyeing the rim, mentally counting the steps, he was poised for another attempt when a photo assistant stopped him. Bryant paused, listened, then looked away in embarrassment as the assistant knelt at Bryant’s feet and tied the budding star’s shoes.

His mother, Pam, laughed at the deference shown her 18-year-old son. “I hope he doesn’t wait for me to do that for him,” she said.

Not a chance. An endorsement contract and roles on the TV shows “Arli$$” and “Moesha” haven’t inflated Kobe Bryant’s ego. Nor are big paychecks and fawning fans likely to change him, thanks to the lessons Pam and her husband, Joe--known as “Jellybean” during his eight-year NBA career--taught their three children about humility, respect and the importance of family.

“It’s crazy,” Bryant said of the fuss stirred by his incipient stardom. “If you sit back and start thinking about it, maybe you could be overwhelmed by the situation. You’ve just got to keep going slowly and keep working hard on your basketball skills. Then, I don’t think your head can swell because you won’t have time to think about it.”

Bryant didn’t go on a wild shopping spree after signing the Adidas deal or his three-year, $3.5-million contract with the Lakers, who acquired his rights from the Charlotte Hornets. When his sister Shaya borrowed his sunglasses during the summer, he simply went without until he was given a pair he modeled in an advertisement.

“I’ve never enjoyed shopping,” he said. “I don’t have the patience. I’m usually playing basketball with one of my cousins. . . . I like to buy my sisters clothes because I want them to look pretty and I know they like to look pretty. I’ll go shopping with them because I want to make sure they don’t buy something that shows off their figures too much. I’m afraid of all guys when it comes to my sisters. I’m very protective, and they’re the same way with me.”

When he found an ocean-view house in Pacific Palisades, he invited his family to move in. Pam, Joe--who gave up an assistant coaching job at LaSalle--and Shaya, 19, accepted. Sharia, 20, stayed in Philadelphia, where she is a senior volleyball player at Temple.

Pam and Joe plan to fly east occasionally to watch Sharia play. It’s only fair, considering that during Kobe’s senior year at Lower Merion High in the Philadelphia suburb of Ardmore, three generations of relatives on both sides of the family--most of whom live within a seven-mile radius--gathered to cheer him on.

The Bryants are openly and unapologetically affectionate, and not only with each other. Pam is apt to invite home to dinner someone she has just met, or offer her jacket to a chilled bystander watching Kobe’s photo session.

“After a game, it’s nothing for Kobe to come over and give me a kiss,” she said. “My daughter [Shaya] is 6-2 and she’ll sit in my lap. They just do things that are not considered cool by other kids, and they don’t care.

“Once, Kobe had the flu and was pretty sick and insisted on playing because it was a big game. He sat on the other end of the bench because he didn’t want to spread germs. He played, and he played fantastic. He went back to the bench, and I saw he had a towel around his shoulders but he was shivering because it wasn’t enough. I gave him my red shawl, and he wore it. How many kids would do that?”

That demonstrative love has subjected Kobe to kidding from outsiders. He shrugs it off.

“It’s mostly good-natured,” he said. “I really could care less. I think it’s good to have a very close family. I think we matured together and we kind of are like best friends.”

Although Bryant’s age prompted Laker forward Cedric Ceballos to joke, “I think he’s got curfew tonight,” his levelheadedness has impressed teammates at the Lakers’ training camp. The 6-foot-6 guard had already impressed his coaches with his athleticism in summer league play, displaying good court sense, ballhandling skills and a knack for generating scoring chances from anywhere on the floor. Scouting reports called him “Grant Hill with a jump shot,” and he can post up against shorter players or, if matched against a taller player, use his skills to take his taller opponent off the dribble.

“He’s a very confident individual, and that’s a positive thing for someone in his situation,” Ceballos said. “He handles himself real well, not like someone just coming from high school. I can’t believe how talented he is mentally, and his focus on basketball, and what he wants to do in basketball. A lot of people would see that as cocky but he’s not cocky. He just believes in himself. It doesn’t come off the wrong way.”

Although Bryant was devastated when he broke his wrist in a pickup game in early September and was idled for five weeks, he didn’t let the time go to waste. He loves to study films of Michael Jordan, not so he can mimic Jordan’s moves, but to analyze how Jordan changes the flow of a game.

“I always tried to hold a basketball, watch basketball, think about basketball,” Bryant said. “People told me to get away from basketball, but I can’t. It’s in my blood. . . .

“I like getting out there [for promotional appearances] and having a good time and meeting people. I like to see the end product, and I take pride in it. I want my product to be one of the best things out there. And I love going in front of the cameras and learning something new. But I understand basketball is what got me here and on top of that, I love to do it so much that it will always be my focal point.”

A model student--he scored about 1,100 (out of 1,600) on his SATs--he’s also a model citizen. His maternal uncle, Chubby Cox, who played basketball at the University of San Francisco and briefly in the NBA, says the worst offense Kobe ever committed was to “put his feet on the couch around my sister.” That’s it? “That can be murder,” Joe Bryant insisted.

Kobe’s high school coach, Gregg Downer, described coaching him as a once-in-a-lifetime privilege.

“I know the high school market very well and I’ve watched it for close to 20 years, and to think there could be another player come into my hands and be this good, that’s an abstract concept,” Downer said. “He’s blessed with a lot of natural ability and great genes, but the work ethic is his and it’s very strong. Kobe has the skills and the maturity and everything you could want.”

He also earned his teammates’ respect without provoking jealousy.

“He’s a motivator,” said Rob Schwartz, a reserve point guard for Lower Merion last season. “He wasn’t really much with pep talks, but when he spoke to you, you’d listen. . . . Even though he was the best player on our team, he always worked hard. One time, he broke his nose at practice. He got up, with one eye [closed], shot with his left hand and hit a three-pointer. It was amazing.”

Bryant fit in comfortably at Lower Merion, whose student body of 1,200 is about 10% black. Neighbors and fellow students describe him as modest and polite, even after his play in leading the Aces to the state championship drew swarms of college recruiters to the school’s sprawling campus and had ESPN cameras setting up in the driveways.

“When he goes to the local gym to play, kids line up for his autograph and he always signs for them,” said Annie Schwartz--no relation to Rob--who used to wait at the school bus stop with him and lives five houses from the Bryants in Wynnewood, on Philadelphia’s posh Main Line.

“No one treats him any differently,” she added. “He’s just a normal kid. For sure, he’s not a Macaulay Culkin.”

Sure, but few kids draw MTV coverage at their senior prom, as Bryant did when he took pop singer-actress Brandy.

“That shocked everyone, that and [nonstudents] lining up to get tickets for the basketball team’s games,” Annie Schwartz said. “But he’s still just Kobe here.”

Pam and Joe agreed that Philadelphia would always be their home, but the family followed Joe wherever his NBA career took him. Pam recalled that Kobe was 3 and they were living in San Diego when her son first showed an interest in basketball, taking a Dr. J mini-basket his uncle had given him and setting it up in front of the TV before Clipper games.

“Right away he started dunking,” Pam said. “I said, ‘Sweetheart, you’ll break it. Don’t dunk. Just shoot jump shots and layups.’ The whole time they were on TV he would play too. He’d have his little cup of Gatorade and his towel and he’d say, ‘Mom, I’m sweating.’ Everything he does, he puts his heart into. He took karate lessons and he was pretty good at that, too.”

When Kobe was 5, Joe went to Europe to prolong his career and the family went along, spending eight years there, mostly in Italy. It was overseas that the Bryants’ bond was forged and they learned to speak fluent Italian. They still lapse into it when they’re among others who speak it, doing it so naturally that it doesn’t seem pretentious or rude.

“When we went over there, nobody in the family spoke Italian and we couldn’t communicate with anybody except members of the family,” Kobe said. “So when we went out, we went out as a group. I had my sisters’ back and they had mine.”

Said Joe Bryant, “Traveling made us close. When we went over to Europe we had to depend on each other because we couldn’t speak the language, so we communicated with each other probably more than we would have in America, where we have TV and radio and so many other distractions. . . .

“The travel helped them see different people, different religions. I think they look at people as human beings, not as a color or religion, so they don’t feel trapped in any kind of stereotypical situation. They’re more confident and relaxed in dealing with people.”

Pam and Joe decided to return to the U.S. when the kids reached their teen years. Having been gone so long, the kids were hit with culture shock. Because their Italian schools had no lockers, they didn’t know they were supposed to lock up their valuables and they were shocked when property was stolen. And for once, Kobe had to navigate strange territory on his own, because his sisters were in high school and he was still in middle school.

“I didn’t have anybody to lean on,” he said. “It was kind of strange because, being away, I didn’t know a lot of the slang that kids used. Kids would come up to me and say whatever, and I’d just nod.”

Basketball helped him gain acceptance. He had played in Italy, getting a grounding in fundamentals, and in Philadelphia he began to refine his skills.

“When I first met him, at age 13, and I saw him play, after five minutes I said, ‘This kid is going to be a pro,’ ” Downer said. “Never was there one moment I doubted that. That it would happen so quickly, I may have doubted that. But I knew if he progressed so quickly and continued to make good decisions, he would someday get there.”

Nor did Pam expect “someday” to arrive so soon. Kobe talked of playing in the NBA when they were in Europe.

“But I’d say, ‘Son, you’re going to college and then you go to the NBA,’ ” she said. “I thought he didn’t understand how it worked, because in Europe they don’t have that college level.”

He understood very well, though, and swayed his parents with the argument that his education in Europe had served him well academically but the lessons that would benefit him the most could be learned only by playing in the NBA.

“In that situation, I don’t think there’s a wrong choice, either way you look at it,” he said. “If you go to college and play basketball there, you meet people and on top of that, you get a good education. In the NBA, you’re learning from the professionals and maturing as a person and as a basketball player, so the education factor is still there.”

His decision was savaged on Philadelphia’s radio call-in shows. Some critics theorized that Joe had pushed him in order to live out a vicarious dream. Joe scoffs at that. He says he would like to have seen Kobe attend college for four years.

“But I knew that wasn’t reality,” he added. “He wasn’t going to go for four, and I don’t think it was fair to put him under that kind of pressure.”

Only four NBA players have made the jump directly from high school--Darryl Dawkins, Bill Willoughby, Moses Malone and Kevin Garnett. All are big men who didn’t have to learn the nuances of playing guard or small forward, but Joe insisted that his son can be the exception.

“People say he’s not 6-10 or 7 feet. I’m saying, ‘Now wait a minute. Sure, he’s not 7 feet but he’s a smart player and he understands the game.’ Nobody really ever said that, and that upset me a little because, to be a guard, you really have to understand the game,” Joe said.

The wrist injury kept Kobe out of contact drills early in camp, preventing Coach Del Harris from assessing his prize rookie’s capabilities. Still, Harris--who was Joe Bryant’s last NBA coach, in Houston--was intrigued by the raw talent he saw in Kobe’s summer league performances.

“It’s not just [his athleticism],” Harris said. “I guess you would say it’s the athleticism combined with so many skills. You get so many athletes who excite you with potential, but they don’t have the ballhandling or shooting skills. And here’s a guy that actually has got all these things. It’s just that it’s in this young body.

“It’s just a matter of how soon will that be able to work against the bigger, older players. We think he’s going to reduce the expected time that would be normal for an 18-year-old because he’s obviously unique.”

Although he didn’t play in college, Bryant has played against his father and his uncle all his life. He has also played in the renowned youth, summer and adult leagues in Philadelphia, which have produced dozens of NBA players.

“Combine that experience with his family background and you come up with a youngster who’s prepared to take this on,” said Sonny Hill, who had Kobe, his father and his uncle in programs he runs in Philadelphia. “He’s not in awe of playing in the pros. He’ll be able to handle the adjustments.

“It may be four years from now until he fully develops. But I can tell you that he will be everything everyone expects him to be. He still needs some nurturing, but Kobe has all worlds open to him.”

The world he is about to enter seems intimidating, but Bryant said he is excited but not fearful about what awaits him.

“I can refer back to my junior year in high school, when I was first coming up and people were starting to recognize me,” he said. “I was the little man on campus. Nobody recognized me or paid me any attention, and that gave me the opportunity to sneak in and do some positive things and learn from the people who were ahead of me. That’s how I feel now. This is a great opportunity for me to get in there and work as hard as I possible can and learn from the great players I have around me and playing with me.

“Basketball is kind of like life. It can get rough at times. You can get knocked on your butt a couple of times. But what you have to do is get up and hold your head high and try again. That’s how I’m going to be. I’m sure there are going to be times guys are knocking me on my back and pushing me and I might start bleeding, but I have to get back up and keep going.”

Former Times staff writer Scott Howard-Cooper contributed to this story.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.