By deferring some earnings, athletes can help themselves and their teams

Heplays for theMemphis Grizzlies these days, but forward Zach Randolph still collects a paycheck from the Portland Trail Blazers.

Randolph is one of the few dozen major-sport athletes who in recent years have been willing to cash a portion of their salary or signing bonus at least a year after it was earned.

These deferrals occasionally arise as a point of contention in contract negotiations and will undoubtedly come up during baseball’s current free-agency signing period. Fans seem to love deferrals when an expensive player takes one to help a team buy a quality player or two in the short term. But fans quickly change their tune when they realize a guy long gone is still cutting into their favorite team’s payroll.

Yet despite the horror stories of players’ running out of cashinretirement,deferred compensation is not very common.

Only one current NHL playerdeferspart ofhisdeal, according to its players’ association. About 10 current Major League Baseballplayers have deferral clauses in their contracts, down from 50adecadeago,according to baseball’s players’ union. A few NFL contracts have deferrals, agents said, but the players’ association could not provide an exact number. Inthe NBA,less than5% of free-agent signings in the last four years included deferred compensation.

“You’re dealing with young people who typically want that money in their possession,” said football agent Kenny Zuckerman.

Randolph’s agent, Beverly Hills-based Raymond Brothers, has persuaded two other clients out of his roster of 10 to accept deferred money.

“My thing is I like to have an automatic savings plan for the guy, so if the wheels fall off the bus, he’ll have the money coming in,” Brothers said. “If he gets another contract, he’ll be even better off.”

The latter is what happened with Randolph. He signedasix-year,$84-million extension with Portland at age 23 in 2004. But $25 million, or about 30%, was scheduled to be paid between 2012 and 2017. In 2011, he agreed to a four-year, $66- million deal with the Grizzlies. This time, he deferred $9.9 million, or about15%.

NBA’s 2011 collective bargaining agreement limited deferrals to 25% of a player’s salary. The NFL also has a maximum, 50%.

Deferred compensation appears tohavebeguninthe 1970s with the American Basketball Assn. As the league tried to steal top talent away fromthe NBA,it offered enormous salaries. But many of the deals were constructed to pay out in small chunks long into the future.

“In some ways, it’s not much different than a team taking out a loan to sign a star,” said Marc Edelman, who teaches sports law at City University of New York. “Let’s spend now and deal with paying later.”

Around the same time in baseball, the advent of free agency led to a flood of contracts with deferred money as teams searched for ways to absorb larger and longer deals. Acceptance of the deferrals began to wane when teams wouldn’t offer interest on the later payments.

The financial stability of teams also came into question. The Pittsburgh Penguins owed Mario Lemieux about $30 million when the team filed for bankruptcy in 1998. Deferred salaries are an unsecured form of credit, meaning they are not legally guaranteed if a team runs out of money.

Lemieux converted the outstanding balance into a stake in the team, and only after he became the team’s ownerdidhepullout someof what he had been owed.

Jeff Citron, a Toronto attorney who has advised on players’ contracts, said Lemieux rolled the dice with a team that was in a tenuous situation.

“People may have learned their lessons a bit with those large sums and lost their appetite for deferrals,” he said.

Baseball stars Alex Rodriguez and Manny Ramirez could have lost millions in deferred salaries during the Texas Rangers and Dodgers bankruptcies. But in both cases, new owners agreed to honor the non-guaranteed obligations, and the players’ union never would have allowed otherwise.

Now, Phoenix Coyotes winger Shane Doan is believed to be the only active hockey player waiting on a deferred payment. He signed a four-year, $21.2-million contract that included a $2-million signing bonus. The first million will be due in the 2016-17 season and the second million the next season.

Doan sought a guaranteed signing bonus because of the looming lockout, said his agent, Terry Bross. With new ownership on the horizon, Phoenix couldn’t absorb the bonus immediately.

Several agents said that when NFL teams defer a payment, most often it’s the signing bonus on deals struckinthe cash-poor early spring.

“Sometimes, they’ll want to wait until April, May or June after getting early returns on season tickets,” said agent Bob Lattinville.

Football teams pay salaries during the course of the regular season — with the Tennessee Titans being the most recognizable exception. The Titans have for years stretched payments into March to help players budget through offseasons.

Many contract experts see deferrals as a bad deal for players in today’s economy, except inspecial circumstances or when a player lacks the discipline to wisely manage his money.

On one hand, leagues funded by television rights fees are in better financial shape than ever. Spreading out payments over a longer period helps teams reduce their lines of credit, and money not spent now can be invested. Unfortunately for them, the way leagues count deferrals rarely helps teams with salary-cap or luxurytax concerns. Citing a policy of not discussing contracts, several teams contacted by The Times declined to comment.

For players, deferrals lessen the stress of shifting from a $1-million annual income to zero at retirement. Pensions and other forms of retirement benefits often don’t kick in for several years. In the NFL, for example,players with at least four years of service collect annuity checks once they are 35 years old and out of the league for five years.

In cases of emergency, investors have monetized deferrals for players, though at a significant cost and only if teams are willing to buy insurance on the balance.

Deferring salaries also delays payments to agents and tax collectors. States such as California collect taxes fromathletesbasedon the number of days they spend working in the state, including as members of visiting teams. Players who deferred a significant portion of their salary a few years ago to this year must now swallow California’s higher rates for high-income earners.

“No one wants to risk it with how aggressive the tax code has become,” Creative Artists Agency’s Lattinville said.

That’s why in deals today in which both sides agree to a salarydeferral, talks might sour when deciding on an interest rate that protects a player from rising tax rates and inflation.

Several teams have been able to convince veterans to accept deferred money in new or restructured contracts as a way to make room for teammates.

In 2010, Colorado Rockies first baseman Todd Helton agreed to defer $13.1 million of his $19-million salary in 2011 as part of a two-year, $9.9-million contract extension. He’ll collect with interest from 2014 to 2023. The deal allowed the Rockies to retain two of their three key players after 2011.

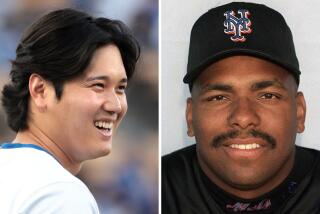

Most famously, the New York Mets reached a deal mid-contract with slugger Bobby Bonilla to defer for a decade his 1996 salary of morethan$5 million. Bonilla agreed to another deferral with the Mets in 2000, setting him up to receive more than $40 million from 2004 to 2035. The deal allowed the Mets to invest the money or spend immediately on more productive players.

Though Bonilla might have lost out on the chance to grow the money himself, he has no complaints. “I had no need for it right away because I was never really crazy with my money,” Bonilla said.

“I hope other players are thinking about living tomorrow like they are living today.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.