Column: Transgender teenage ballplayer at Santa Monica prep school spreads message of hope and acceptance

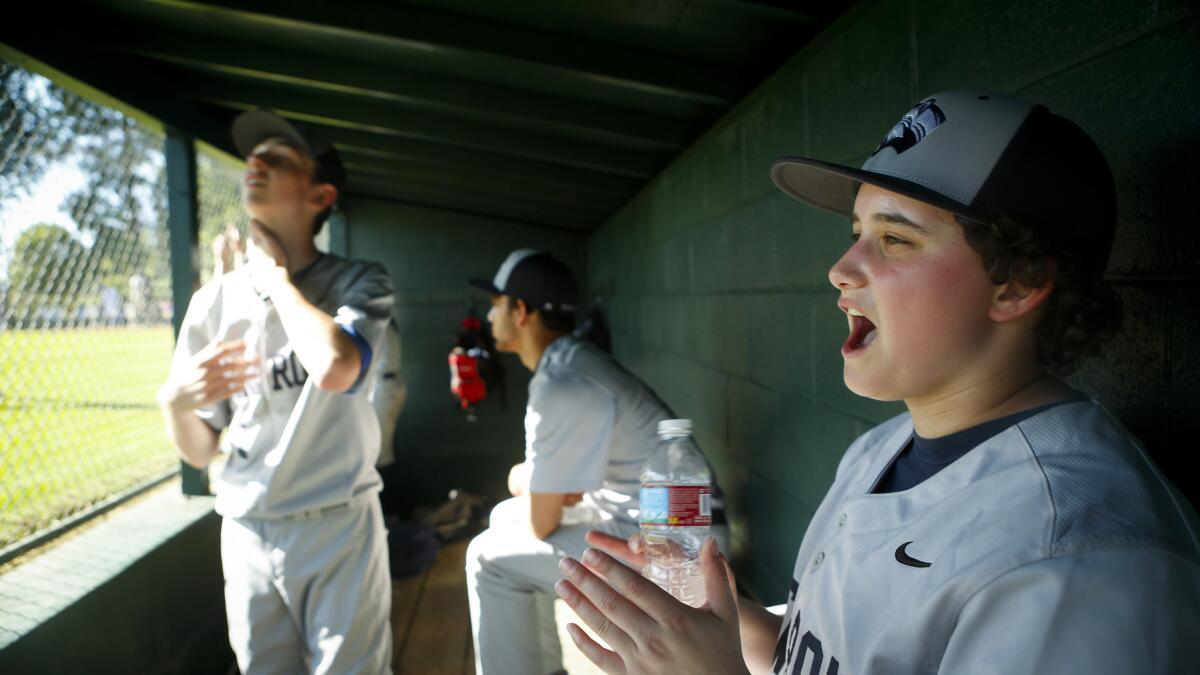

Jake Hofheimer waits in the dugout with his New Roads High teammates before taking the field for a game March 23.

As he steps into his new world, one filled with transparent hope and absent of suicidal despair, there is only one occasion when Jake Hofheimer dares to look back.

It is when he is coming to the plate for the New Roads School baseball team.

Behind him, a dozen or so teammates inevitably will be rattling the chain-link dugout fence with cheers of encouragement, their clatter showering over him like a beautiful symphony.

It is the sound of belonging. It is the sound of freedom.

“C’mon boy!” they shout. “You can do it, man!”

Hofheimer, a 17-year-old junior second baseman and outfielder, is a transgender male who celebrates in the truth that he has finally found his team.

“When they’re banging on that fence and calling my name, that’s when it hits me,” Hofheimer said. “I’m just one of the guys.”

Until he enrolled in the small Santa Monica prep school nearly three years ago, Jake was Emma, a girl whose feelings of being trapped in a hostile body led to depression and a suicide attempt, by hanging. When he arrived at New Roads in the middle of his freshman year, with family support and classmate awareness, he changed his first name, began living life as a boy, and decided the natural next step would be on a playing field.

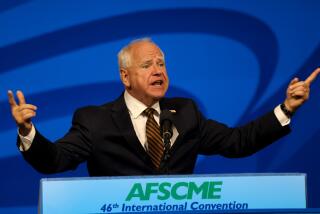

Our school environment is one of diversity and acceptance and, well, to us, he’s just Jake.

— Matt Steinhaus, athletic director at New Roads High

Jake Hofheimer cheers for his New Roads High baseball team during a game March 23

“Sports is great because it’s a place where you’re not judged for being anything other than an athlete,” he said.

He chose baseball because he liked the sport and had once played it as a young girl. He carefully approached New Roads’ coach and athletic director, Matt Steinhaus, with complete honesty. Steinhaus heard his story, slapped him on the back, and sent him out to the diamond.

“He’s just Jake,” Steinhaus said. “Our school environment is one of diversity and acceptance and, well, to us, he’s just Jake.”

This is Hofheimer’s first full season since tee ball, but New Roads is small enough there was room for him on varsity. His teammates know his history, but pay far more attention to his hitting and fielding.

“Yeah, we know Jake is different,” teammate Brandon Deutsch said, shrugging. “We know he hasn’t played very much.”

He doesn’t throw well, so they position themselves closer to catch his tosses. He is still figuring out how to hit, so they loudly cheer for him when he’s batting as if trying to coax the ball to hit the bat.

He’s never an all-star, but he’s always part of the team, hanging in the dugout spitting seeds with the dudes, backslapping and high-fiving and cracking up at the schoolboy jokes. His best moments are not giant home runs or diving catches, but the little instances of proper recognition, words that now empower him and never get old.

“C’mon boy!” they shout. “You can do it, man!”

::

He’s Jake, because he was always Jake.

When he was a little girl named Emma Hofheimer playing make-believe games with younger brother Tommy in their Hancock Park home, he would always adopt the role of a boy named Jake. He believed the name just sounded like him.

“I never felt like a girl, I always felt like a guy, I just didn’t know how to express it,” he said.

Jake Hofheimer is a transgender teen who feels at home playing baseball.

His mother Lisa, who works for a private charitable foundation, and father Josh, a lawyer, picked up on oddities that they later learned were clues.

One night, Jake looked at his mother and said, “Mommy, I think God is sometimes a boy and sometimes a girl.”

Later, Josh and Lisa were having trouble convincing Jake to wear a dress to temple, and became resigned to his daily uniform of T-shirts and basketball shorts.

“Looking back, you see things that maybe you didn’t see at the time,” Lisa said. “This landscape is moving faster than we’re moving as human beings.”

When it was time to enter middle school, Jake and his family decided an all-girls’ school might be the place to help him find his identity as a female.

“I was trying so hard to conform to society’s standards,” Jake said. “I thought, oh well, maybe I can figure out what kind of girl I am. I thought there would be other girls like me. A sisterhood.”

Instead, it was a nightmare. He says he was bullied by other girls uncomfortable with his appearance. Instead of finding acceptance, he says he became an outcast.

“I was bullied because I was so tomboyish,” he recalled. “I was bullied for being different.”

He says once on the school bus, girls surrounded him and mockingly took his photo, forcing him to change buses. He says he was called “he-she” and “it” on social media.

The bullying was too much to take when combined with puberty for an adolescent girl who identifies as a boy.

“When my boobs came in, it was one of the worst experiences of my life,” he said.

This led to one dark afternoon in an upstairs closet. Alone and feeling hopeless, Jake wrapped a belt around his neck, attached it to a hook on the wall, and stepped off a chair.

“I was depressed, upset and angry,” he said. “I was like, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ I wanted to crawl out of my skin.”

But the hook pulled out of the wall and Jake fell to the floor. Studies show that more than 50% of transgender youth will try to commit suicide at least once by their 20th birthday.

“I guess my hope [talking about this] is that other trans youth and teens will see that they’re not alone,” Jake said.

He finally realized others shared his struggle when he attended a seminar at his all-girls’ school that featured a transgender woman speaker.

“Afterward I said to myself, ‘Oh my God, this makes so much sense, this explains how I’m feeling, I’m not alone, there is this whole community out there,’” he said.

In the spring of his eighth-grade year, he told his parents he identified as a male. They reacted as honestly as his admission.

Said Lisa: “I was sad, but I said, ‘You’re my child and I’ll always love you.’”

Said Josh: “At first I said this was a phase. I said, ‘You’re only 14, your brain is not fully developed yet.’ But eventually I came around to realize, this is who he is, and I’m so proud of him for it.”

Within weeks of Jake’s public acknowledgment, his parents sent him to a gender therapist. Six months later, he was transferring to New Roads. Soon, everyone was calling him Jake.

Early in the process, his proudest moment was the time he went to Starbucks and gave them his new name to write on a coffee cup. Then his journey led to the baseball field, which fit him like, well, a glove.

At the all-girls’ school, he was a swimmer, but the suit never felt right. A baggy baseball uniform felt perfect.

His also tried snowboarding, and while he could be himself on the slopes, he was always alone. Baseball gave him teammates.

He’s the smallest (5 feet 4) and least-skilled player on the team, but when he tucks his blue cap low over his curly hair and pulls his pant legs low on his cleats, he looks and feels like a ballplayer.

“I am always so happy when I’m playing,” he said.

Hofheimer initially was worried about breaking CIF rules, but his involvement is supported by CIF Bylaw 300D, which states, “All students should have the opportunity to participate in CIF activities in a manner that is consistent with their gender identity, irrespective of the gender listed on the student’s records.”

It was no problem because New Roads had accepted him as a male.

“Jake has had a challenging journey to get to a place where he feels comfortable in himself,” said Luthern Williams, New Roads Head of School. “Now he should have the options available to any young man.”

Hofheimer is not the only transgender teen at New Roads, which has 651 students from K to 12. The school was founded in 1995 on principles reflecting the diversity of Los Angeles.

“Kindness is the foundation of our community,” Williams said. “What matters most here is the content of the character of the student, who they are, the choices they make, how they treat others. Parents expect us to lean into situations where other schools would be wary to go.”

So it happened that the first assist by a teammate came not on the field, but in a restroom. When Jake was concerned about using the boy’s restroom at school, he was accompanied there by senior first baseman Wills Price.

Until Jake felt comfortable, the 6-foot-4 Price stood guard outside the stall.

“He was really insecure at first, going through tough times,” Price said. “We all wanted him to fit in as well as possible.”

Jake has since found a home both at school and in the dugout. His teammates have also figured out his challenges and adapt to them.

When he can’t make the throw from second to home, the catcher takes a few steps toward the infield. When he’s struggling at the plate, they rock the dugout fence and yell tips. There are no locker rooms for the baseball team, so that hasn’t been an issue.

“Jake loves being out there, being part of the team, this is a degree of validation for Jake,” Steinhaus said. “It’s all very empowering.”

Added teammate Deutsch: “We all know Jake is learning. But at our school, anybody can be anybody.”

I would tell parents, love your kid, love them unconditionally, don’t try to change them.

— Jake Hofheimer, on raising a transgender youth

Jake Hofheimer shares a laugh with a teammate in the dugout during a New Roads High game.

When Jake decided to tell his story here, Steinhaus warned him of the ramifications of telling future opponents about his life.

“I told him, ‘This will bring attention, a lot of it might not be as positive as you want, and you might be fighting back against some people who say, ‘That’s the guy in the paper,’” Steinhaus said.

Jake understands. He says he is willing to hear words of hate in order to spread the message of hope.

“Whatever someone says, it’s just going to prepare me for the real world, right?” he said with a chuckle. “I hope this will encourage trans youth who are nervous going out for sports. You’re not a trans kid, you’re just an athlete.”

Through it all, Jake’s parents have stood beside him, often literally. At a recent game, his father left work early to stand behind the batting cage and cheer with a handful of other parents. His mother still has the bat mitzvah photo of her child wearing a dress, but is quickly collecting photos of the swaggering ballplayer.

“I would recommend to parents to look in their child’s eyes, look at their smile, look beyond any gender, and know this is your offspring, this is going to be your child’s story, and you’re going to want to be part of it,” Lisa said.

Jake’s advice to parents of trans youth reflects his own story.

“I would tell parents, love your kid, love them unconditionally, don’t try to change them,” he said. “And to kids I would say, if your parents aren’t moving at a pace you’d like them to, just remember, it’s really hard for them because they’re losing a son or daughter and gaining a new kid.”

Jake, whose chest currently is constrained beneath a binder, is hoping to begin hormone treatment at some point and also would like to undergo surgery to his upper body. For now, he’s happy to just be a dude on a baseball team, one who recently filled the dugout with jeers for a teammate for forgetting a vital piece of equipment.

The player ran off the field complaining he was not wearing a protective cup. Jake Hofheimer and the rest of the New Roads Jaguars howled.

You know, boys.

Follow Bill Plaschke on Twitter: @billplaschke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.