Blind swimmer is true inspiration

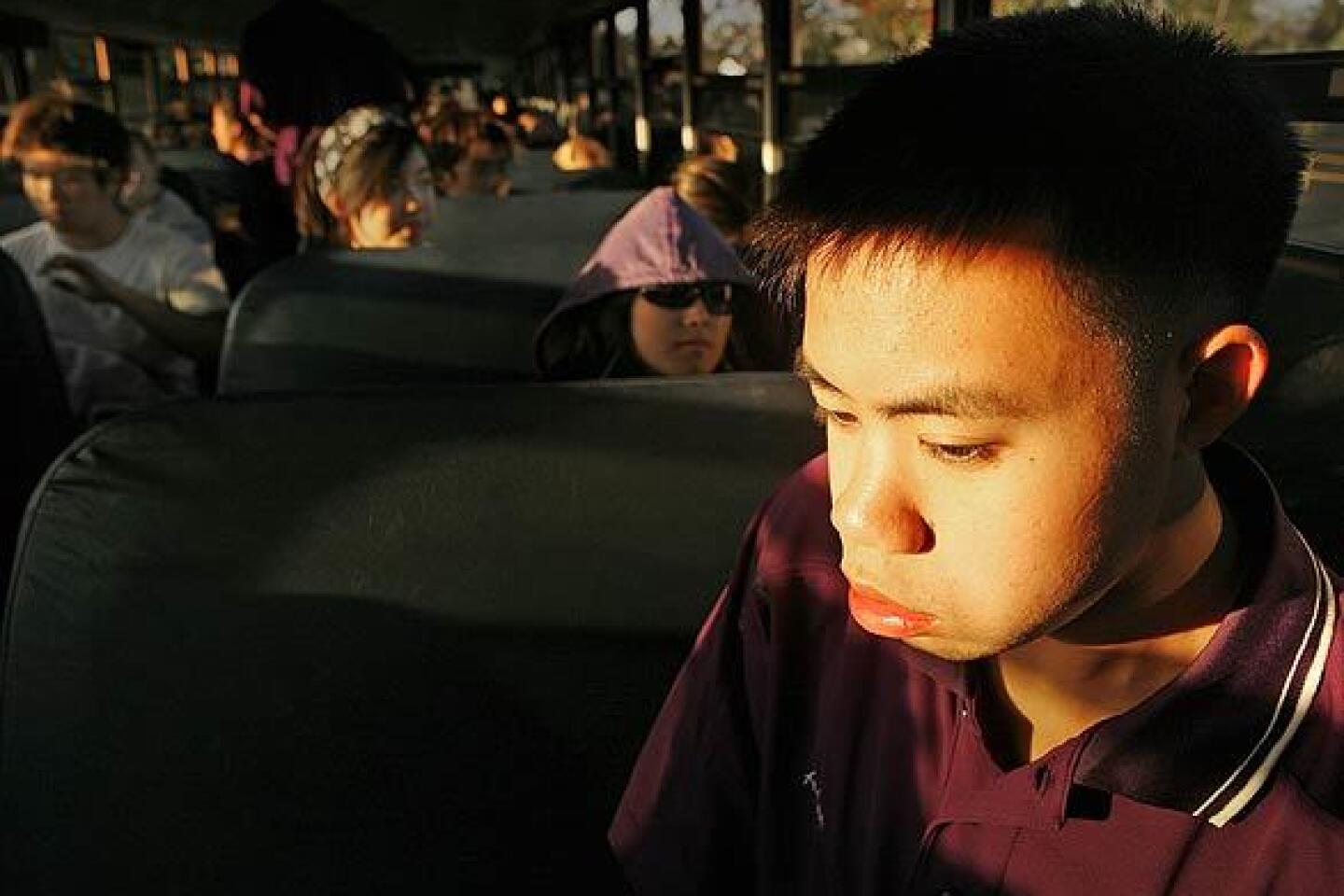

A loud beep tells the six swimmers standing on starting blocks to dive into the pool. Andrew Luk of Diamond Bar, wearing goggles, pushes off from the wall as his competitors splash and dart ahead in the 500-yard freestyle race.

By Lap 18 of the 20-lap race, Luk is swimming all alone. Drama builds with each stroke because those watching Luk can’t believe what they are seeing. The clapping is increasing, the cheering is becoming more boisterous and the chanting is growing louder, “Go, Andrew, go.”

Luk is blind, and the fact he has the courage to compete for his high school swim team is emboldening teammates and opponents alike.

“It’s amazing and wonderful,” said Eve Chen, the mother of a Diamond Bar swimmer.

Luk’s story is more than inspirational. It’s a triumph of the human spirit.

Luk joined Diamond Bar’s junior varsity swim team last month after much agonizing over what he should do with his life.

At 5, he lost his vision because a 1.1-centimeter tumor damaged his optic nerves. Radiation reduced the tumor’s size, but its location on the brain stem made it too risky for surgery, leaving him blind and partially deaf. He can detect light and darkness from his left eye but nothing from his right eye.

As the years went by, he’d swim for fun, but making the decision to join a team was never considered, until last year.

“It was a need to be part of something and get out and do something I enjoyed because for a long time I’ve been sitting around and talking about what my future could hold but never got up and did anything,” he said.

With the urging of teachers and counselors, he enrolled last summer in a competitive swimming program at Mt. San Antonio College run by Jodi Lepp, an age-group instructor for Brea Aquatics.

“I thought it was awesome that he had no fears of jumping in and was willing to get his feet wet,” she said.

She taught him fundamentals of swimming competitively, though she had never worked with a blind student before. Through repetition and learning to count his strokes, he figured out when he would be approaching a wall.

“If you practice it every day, you get more comfortable,” Lepp said. “The thing I love about Andrew is that there are other kids who will complain, ‘My toe hurts, my leg hurts.’ And he goes, ‘What’s next?’ He motivates me.”

Luk joined Diamond Bar’s swim team in February. He was a 16-year-old sophomore welcomed with open arms by Michael Spence, a dedicated, always positive veteran coach who has a Santa Claus-like white beard and a “big heart,” as one parent put it.

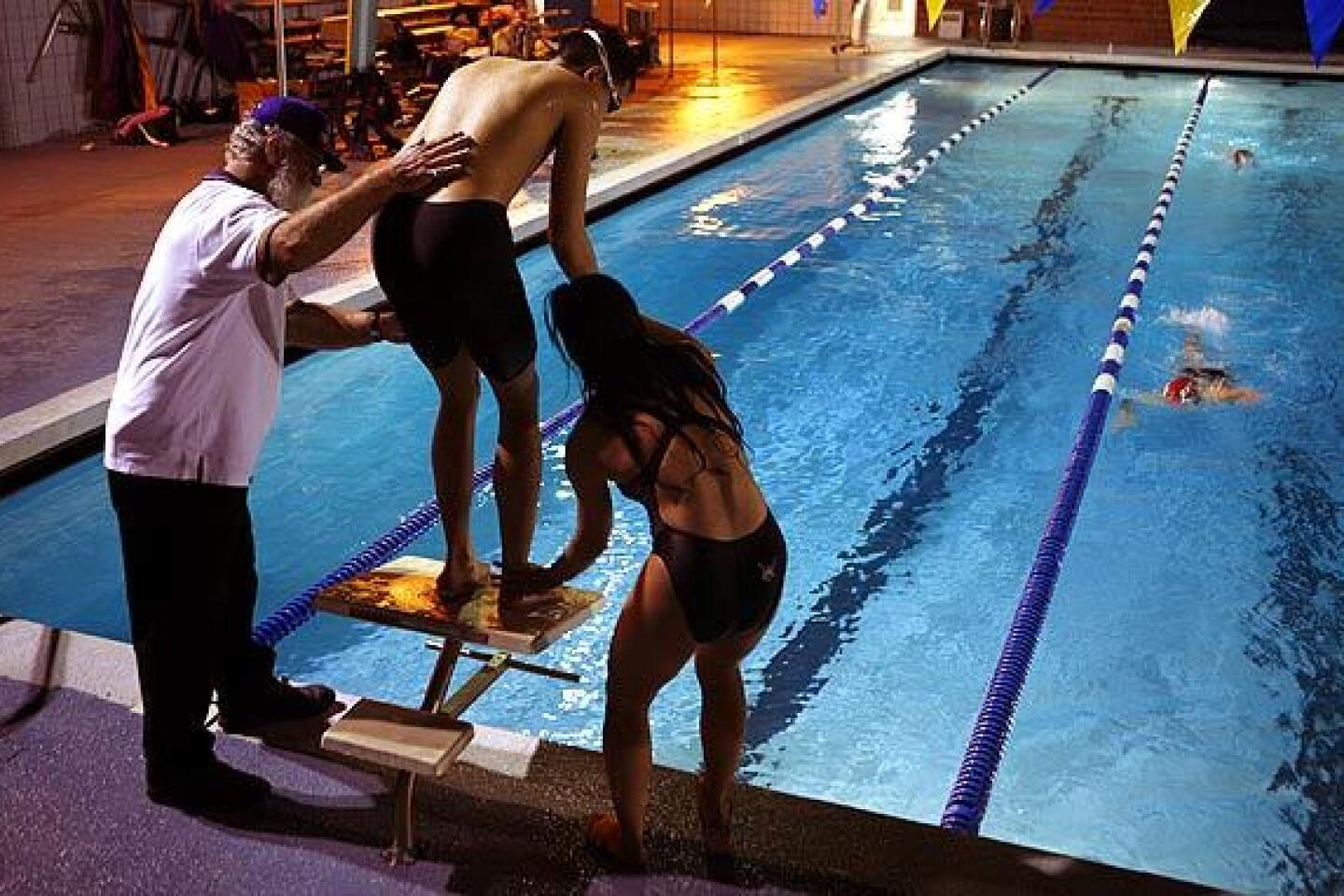

Spence immediately endorsed the idea of Luk competing for Diamond Bar. And he assigned one of his varsity swimmers, senior Lynn Han, to serve as his mentor and personal coach.

Before each race, Han takes Luk by his arm and guides him to the pool rail, where he gingerly drops into the water for competition. Han is one of two tappers who hold a 75-inch long white pole with a tennis ball fastened at the end to touch Luk as he nears each wall. It’s the way he avoids banging his head when he loses count of his strokes.

Han has taught him how to refine his stroke and swim in a straight line within his lane.

“He’s competitive, he’s passionate,” she said. “His attitude is determination.”

In his first race this month, Luk’s time in the 500 free was 9 minutes 55.14 seconds. Two days later, his time was 9:32.45. In his next race, it dropped to 8:54.28. The personal bests keep coming, and last week, he practiced for the first time diving into the water, a dangerous maneuver for someone who is blind but important toward improving his time.

Winning, though, isn’t his top priority.

“More important to winning -- and I want to win badly -- is just learning to work as a team, learning to be dedicated to a sport, learning to be disciplined,” Luk said.

Luk lives in Chino Hills. His older sister attends UCLA and is studying to become a doctor. He has two younger sisters, ages 11 and 8. His mother, born in Indonesia, and his father, a native of Vietnam, run a furniture business.

Royani, his mother, said after watching her son compete in his first swim meet, “It was so emotional. I’m very proud of him.”

Of the estimated 56,000 kids who are blind in the United States, approximately 100 are competing on high school or club swim teams, according to Mark Lucas, executive director of the U.S. Assn. of Blind Athletes. Blind swimmers have been competing in the Paralympics, and the USABA has more than 3,000 members who compete in 11 sports.

Luk, 6 feet and 165 pounds, gets around Diamond Bar’s campus with the help of a cane. He has a laptop that allows him to translate letters in Braille. He’s visited once a week by a mobility instructor and has an aide lookings out for him during the school day. And then there are the many students who admire his commitment to participate in the high school experience.

“It’s pretty brave of him,” freshman swimmer Casey Eng said. “To come out here and play sports and do something with his life is a true inspiration.”

Luk had a 3.8 grade-point average last semester and is well-versed in a variety of subjects, including politics, music and sports. He plays the piano and listens to countless radio programs. He said he might want to become a journalist because he likes to write and recently won a trip to Spain for one of his essays.

There’s always the hope that a medical breakthrough could restore his vision, but he said, “That’s something that leaves you on the edge of your seat, but you don’t live your life hoping it’s going to bail you out.”

Luk appreciates the new friends he has made and the support he has received.

“It’s been the most touching thing, the opposing team coming up and congratulating me and complimenting me and telling me that I’ve inspired them,” he said.

Last week, during a swim meet at Villa Park, most of the home swimmers were scattered during Luk’s race. They were either eating a snack or talking among themselves. Diamond Bar’s swimmers were all cheering and rooting for Luk.

Then, on the final two laps, with Luk the only swimmer still competing, there was a magical moment. Villa Park swimmers stopped whatever they were doing and turned their attention to their pool. They started to clap. Everybody in the swim complex was focused on Luk as his coach, Spence, kneeling on the starting block, exhorted him to “reach” with every stroke.

Luk finished seventh in the field of seven, but the lesson he’s teaching about living life to its fullest sent chills through my body.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.