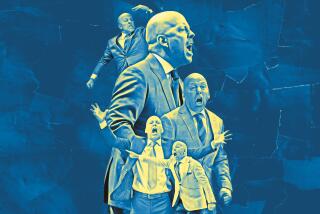

Column: After 29 years waiting for his shot, this basketball coach put his team ahead of his Stage 4 cancer

After being diagnosed with Stage 4 intestinal cancer, Danny O’Fallon said he never considered giving up coaching the Roybal boys’ basketball team.

The great and powerful Danny O’Fallon paced the cramped locker room, his sweater and jeans hanging loose, his eyes tight.

“Nervous?’’ he shouted at the thin shoulders and young faces of his Roybal Learning Center basketball team.

“No sir!’’ they shouted back.

How could they be nervous? They just sweated through four months as the only unbeaten high school boys’ team in Southern California while playing for a coach battling Stage 4 intestinal cancer.

“Scared?”

“No sir!’’

Of course they weren’t scared. Scary was watching their coach struggle through practices when he was sometimes barely able to stand. Scary was fighting to win games for a coach who once finished a game, retired to his car, and vomited all the way home.

“Everybody ready to play?”

“Yes sir!’’

The Titans, undersized and outmanned and still 19-0, were more than ready for Tuesday’s first-round state playoff game at Providence High in Burbank. Through his frailty, O’Fallon had taught them power. Through his illness, he had taught them strength.

This court was their healing. This night was their message.

O’Fallon sucked in his breath as he slowly stepped into the noisy gym while girding his weakened body for another two-hour grind.

“This game,’’ he whispered, ‘’is my life.’’

::

He has lost count of the gym floors he has swept, the snack bars he has worked, the school buses he has ridden, always in the background, forever in the shadows.

Danny O’Fallon, 48, was an assistant for 29 years before finally getting his first varsity head coaching job last season at downtown’s Roybal Learning Center.

He has coached everyone from grade-school girls and junior-varsity boys to awkward high school giants who had to be taught how to dunk. He has coached in a converted church where his team had no bench-warmers because there was literally no room for anybody to sit on the bench. He has coached a team that employed the style of playground basketball because, well, they practiced on a concrete playground.

He has coached with a flip-score scoreboard, with a scorekeeper who had to scream out the time because there was no clock, and with more kids on the court than fans in the stands.

“Sometimes my biggest luxury was having two rims,’’ he said. “I can say that I always had two rims.’’

He is 6 feet 5, but he never played beyond Culver City High because of a knee injury, so he knows what it’s like to dream, and he fostered those dreams in schools from Gardena to Baldwin Park to Culver City to even Santa Monica City College.

You can look closely at him and immediately recognize he is a gym rat. He has a faint scar on his forehead from diving for a loose ball.

You can listen to him and instantly tell he is one of those anonymous teaching coaches. All he talks about is his kids.

“Helping young people reach their goals, teaching them about how the court imitates life, that’s everything for me,’’ he said.

He is such a background guy that when an official from Roybal called him two seasons ago, it was for a coaching recommendation for someone else.

“I told him, ‘Why not me?’ ’’ O’Fallon said. “I thought, ‘This could finally be my turn.’ ’’

He was convincing enough to be hired to shepherd a young program in a public school that opened its doors in 2008. He was hungry enough that he took the job for a stipend of $2,800 a season.

“To tell you the truth, I would have done it for nothing,’’ he said.

There was no real basketball culture, so he created one, bringing in fundamentals and discipline with a sense of belonging. He immediately announced that the gym was their home and the team was their community, leading to what has become their trademark cheer ...

One-two-three-TITANS-four-five-six-FAMILY.

“Coach O’Fallon came here and changed everything,’’ senior guard David Rauda said. “He made us all care about basketball, and about each other.’’

He led them to a 14-7 record in his first season, and they won eight of their last 10 games, so when this season began with four straight decisive wins from his senior-laden lineup, O’Fallon just knew.

“I thought this could be something special,’’ he said.

Then, almost as quickly, it became something nightmarish.

After struggling with intestinal troubles for several months, O’Fallon was summoned to his doctor’s office on the first day of December and given news so grim he immediately broke down in tears. He was diagnosed with Stage 4 intestinal cancer that had spread to his liver.

“I was dumbfounded,’’ he said. “Usually you hear Stage 4, you think, death sentence.’’

After composing himself, he immediately jumped in his car and drove to the only place that made any sense. He drove to basketball practice. Once there, accompanied by his wife Dr. Chonn Ng, he pulled his team to the side of the gym and delivered the news.

“He told us he was sick, real sick, and we were like, speechless,’’ senior guard Jonathan Sirait said. “It was heartbreaking.’’

Then it was loud, kids weeping and hugging and openly wondering if their coach was going to die.

“Pretty much everyone was in shock,’’ Rauda said. “To be honest, I still can’t comprehend it.’’

As soon as they calmed down, Ng informed them of new necessary precautions they must take with their sick coach. They couldn’t come to practice if they were ill. They had to make sure their hands were washed. And, most difficult of all on this close team, there would be no more handshakes or hand slapping with O’Fallon. Since then, the Titans have led the league in fist bumps.

After his wife spoke, it was O’Fallon’s turn again, and he was typically brief.

“I told the kids, ‘I’ll give you guys five minutes, collect yourself, you’ve got work to do,’ ’’ he recalls. “You’ve got a season to finish.’’

Fallon then met with school administrators with a plea to be able to finish the season. His message to them was unmistakable.

“I was like, ‘If you guys take this away from me, you will kill me,’ ’’ he said. “I told them, we have something special here, and if I can physically make it, I want to be here.’’

Roybal officials agreed without even making the typical request of a doctor’s note. They recognized special, and saw it not only in this season, but also with this coach.

“He’s not only been great for our program, but great for our community and it was like, whatever he needed,’’ said Oscar Letona, the Roybal athletic director.

It turns out, what he needed as much as treatment was his team’s effort, its intensity, its togetherness.

“Pardon my language, but all he needed was for those boys to play their asses off,’’ Ng said.

And they did so, immediately. In their first game after his diagnosis, Roybal beat Contreras 60-39. In their next game, the Titans beat Mendez 82-46.

With one starter as small as 5-3, only one player taller than 6-2, and nobody able to dunk according to the coach, the Titans nonetheless continued to play huge, winning game after game, mowing through the City Section’s Central League in historic fashion.

“Knowing how coach was fighting, it made us fight for him,’’ Rauda said. “The strength that he has, his caring, his passion, it carried on to the whole team.’’

Sometimes O’Fallon’s fight, which included a weight loss of 50 pounds and an emergency bowel surgery, would be overwhelming. He coached one game hours after his first chemotherapy session, barely enduring the final minutes before spending the entire 90-minute drive home vomiting in a plastic grocery bag as his wife tried to find side streets to avoid the maddening traffic.

Sometimes, though, his fight would overwhelm. He once missed a game at Bernstein after a chemo session, handing the leadership to assistant coach Travon White. But when he saw on his computer that they were trailing by a point at halftime, O’Fallon picked up the phone and “FaceTimed” a student manager. She brought the phone into the Roybal huddle, held it up high for everyone to see, and O’Fallon shouted instructions to his stunned team. They proceeded to outscore Bernstein by 10 in the second half and remain unbeaten.

“This year has been about no excuses, no second chances, no we’ll-get-them-next-year,’’ White said. “It’s got to be now. Go and win now.’’

There have even been no excuses when both O’Fallon and White, who teaches and coaches at a day school in Encino, could not make practice. On those couple of occasions, the players stayed in the gym and simply practiced by themselves.

“He carries us, we carry him,’’ Rauda said.

They carried each other through an unbeaten regular season and to the final game of the City Section Divison III playoffs, where they defeated Sun Valley Poly for the first City title in the school’s brief history.

At the final buzzer, standing alone in front of the bench, O’Fallon dropped to his knees, put his hands on his head, and wept.

“I was crying not because of what I’ve been through, but because of what we’ve been through,’’ O’Fallon said.

Moments later, the entire team joined him for a giant hug that marked the beginning of their journey to the state tournament, where the 15th-seed Titans would play at heavily favored second-seed Providence.

“We’re exactly where we want to be,’’ he barked at the team at practice on the day before the big game. “We’re warriors!’’

::

They are warriors, but they’re still kids.

They weren’t nervous, and they weren’t scared, but they were emotionally exhausted, and they never had a chance.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

The game against Providence felt like it lasted about five minutes, the Pioneers running out to a 27-2 lead after one quarter and rolling to an eventual 73-33 victory.

Providence was classy in victory, even hanging, “Stand Up To Cancer Go Coach Danny O’Fallon” signs on the wall.

“They are a totally inspirational story, they are what sports are all about,’’ said Joe Sciuto, Providence head of school.

The Titans were nonetheless crushed. Long after the final buzzer, O’Fallon remained in his seat with his head in his hands. Behind him, his wife and his senior co-captain Rauda hugged and cried.

But the pain didn’t last long. If you think this is going to have a sad ending, you’ve come to the wrong story.

O’Fallon walked off the court to a standing ovation from the remaining fans of both teams. He stopped to say that the final score was not the measure of this team, that victory over this season had long since been achieved, that no scoreboard could tally the inspiration that had been given and received. He said, incidentally, that he would use that inspiration in another chemotherapy session the following morning.

“I’m not going to show fear, I’m going to beat this, I’m going to win,’’ he said. “I’m not going to flinch, I’m not going to blink, I’m not going to call timeout when you think I have to call timeout.’’

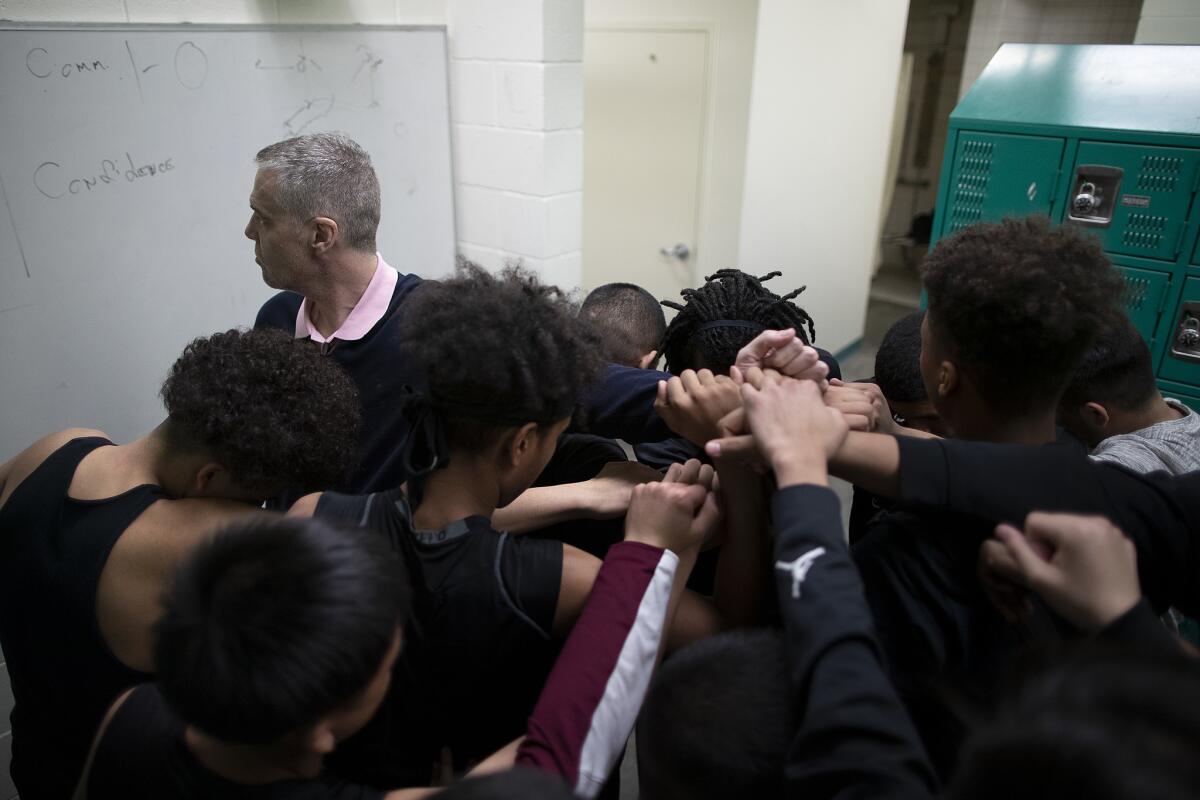

Inside the locker room, he exhorted his crying team one last time.

“I am so proud of you,’’ he said. “I am so, so proud of you guys.’’

Then the great and powerful Danny O’Fallon gathered his kids together for a final huddle, only this time it was a hug, and this time there were no fist bumps, just hands locked into other hands, heads touching, eyes clearing, voices full, hope rising.

One, two, three, TITANS, four, five, six, FAMILY.

Read more of Bill Plaschke’s work and follow him on Twitter @BillPlaschke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.