America’s Cup sailing is no breeze

With giant new high-tech boats, the crews have to work hard just to keep them afloat, and danger is always lurking during races in San Francisco Bay.

The black Lycra suit comes first. Thin and tight, it will not keep out the cold entirely. Shannon Falcone stretches it over his 6-foot-5 frame and muscled shoulders. Then he puts on ankle braces and high-top shoes.

"Injuries are pretty common," he says. "Ligament issues."

His flotation vest comes equipped with an automatic homing beacon, a small oxygen bottle containing enough air for 30 breaths and two knives for cutting his way out of fabric or netting should he become trapped underwater.

Extra body padding remains hanging on the rod. Falcone needs freedom of movement for the grueling hours that lie ahead.

"You get pumped putting on your gear," he says. "You just want to go."

With the final addition of a crash helmet and harness, his outfit weighs almost 16 pounds and makes him look like a commando. Or a stormtrooper from "Star Wars."

Falcone is neither. He is a sailor in the America's Cup.

The America's Cup resumes Thursday with two races scheduled on San Francisco Bay. The competition pits Falcone and his crew mates on Oracle Team USA against a challenger, Emirates Team New Zealand, in a best-of-17 series.

Starting out with a two-race penalty, the American boat has fallen behind and needs to rally. But that is only half of the story.

This edition of the Cup has been part spectacle, part laboratory experiment, thanks to the 162-year-old regatta's quirky conventions.

Unlike other major sporting events, it is held at irregular intervals with shifting rules that often spur lawsuits among the racers. The defending champion gets to choose not only the site but also the type of boat.

Shannon Falcone, left, a grinder for Oracle Team USA, wears a special sailing outfit that weighs almost 16 pounds. (Guilain Grenier / Oracle Team USA) More photos

When Oracle won in 2010, owner Larry Ellison made big changes. Eager for more fan appeal — NASCAR on water — the technology billionaire selected the AC72, a sleek catamaran that travels at high speed, with high risk.

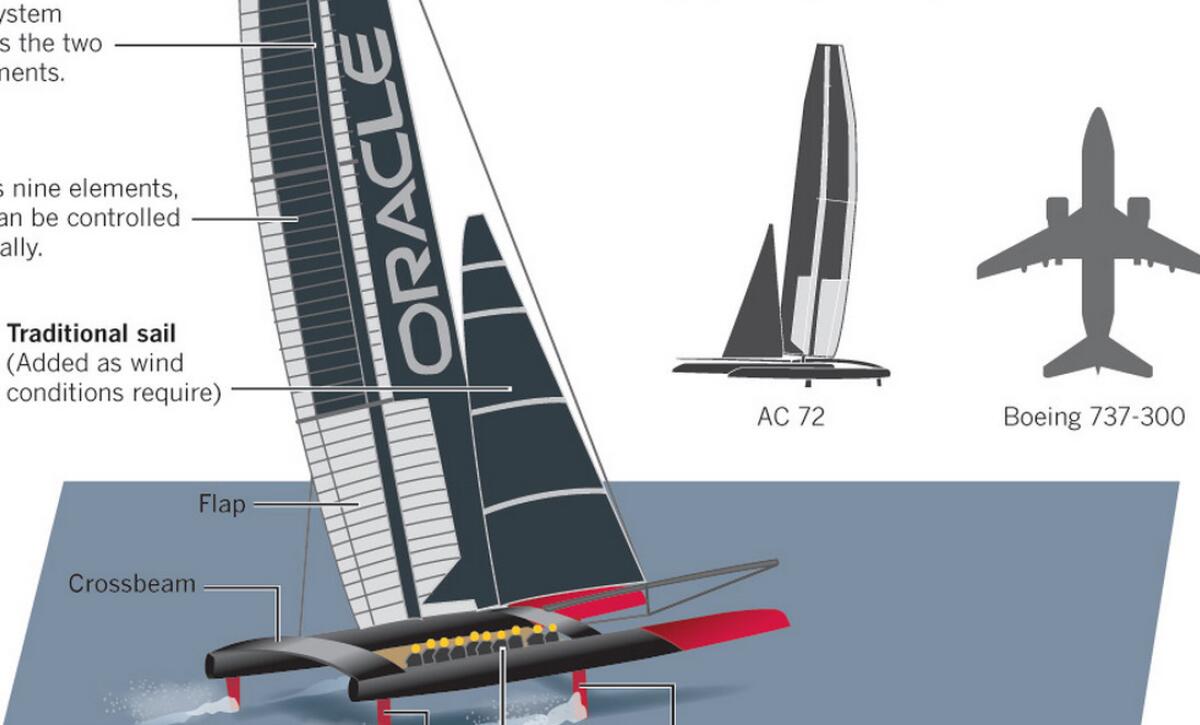

The 72-foot craft features a pair of blade-like hulls made of glossy carbon fiber and a rigid wing towering overhead instead of a mainsail. It can accelerate to well over 40 knots (46 mph), with all 6.5 tons of boat rising above the surface on slender hydrofoils.

"It's like a Formula One car," Oracle skipper Jimmy Spithill says. "As soon as the boat lifts up, you're hitting the turbo-boost."

SAILING SCIENCE: How America's Cup boats use innovative design for speed and power

Ellison's choice drew criticism from the start, especially from traditionalists.

Anyone can vie for the Cup, but only three other boats decided to spend the $100 million or so required to mount a serious campaign. Well before the start of competition — a series of races to select a single challenger — a Swedish boat capsized during practice, killing respected sailor Andrew "Bart" Simpson.

Asked about this nascent form of racing, Falcone thinks a moment, scratching at the black stubble on his face.

His words emerge in a curious accent, blending his Italian heritage, a childhood in the West Indies and years of English boarding school.

"Everything on these boats happens at such a fast pace," he says. "It's definitely a white-knuckle ride."

Just moments into the most recent Cup race, on Tuesday, Falcone is already breathing hard. Tucked into a narrow cockpit along the port hull, he grabs hold of a two-handled crank and begins turning furiously as if reeling in a colossal fish.

The 32-year-old serves as a workhorse on Oracle's 11-man crew. He and seven other "grinders" must drive winches and generate hydraulic power so the back of the boat can control the giant wing and hydrofoils with the push of a button. Bursts of cranking give way to brief rest, followed by more exertion.

"We have our electronic displays," Falcone says back ashore. "But you can basically sense the load by how much resistance there is in the handles."

The physical challenge also includes running.

Because the boat sails at a tilt, the crewmen align themselves along the high side for balance. With changes in direction, the AC72 tilts the other way and they must scramble more than 40 feet to the opposite hull.

This mad dash lasts only a few seconds, but Falcone says it can seem longer. He finds himself sprinting uphill while trying to remain upright on a shifting surface that threatens to buck him into the Bay's 60-degree water. His legs burn and his arms keep pumping.

"Sometimes," he says, "you feel like you're not getting anywhere."

There are no timeouts, no referees to stop the action during the 25-minute races. On most days, the schedule calls for doubleheaders, which keeps the boats out for more than two hours.

Growing up in Antigua, cruising the warm Caribbean waters, did not prepare Falcone for this. Neither did racing traditional yachts.

The 130-person Oracle team — which includes full-time craftsmen, designers and engineers — has spent more than a year in a shorefront warehouse here preparing for this summer. The sailors acclimated to the AC72 with preliminary races and countless hours in a gym that featured grinding stations and a full-scale replica of the webbing that stretches between the boat's hulls.

During practices, they wore biometric devices that recorded vital statistics. The 34-year-old Spithill says: "When the trainers looked at the data afterward, it looked like a couple of the guys were having heart attacks."

The sailors' daily regimen burns as many as 5,000 calories, making it tough for Falcone to keep his weight at 225 pounds.

Every free moment offers a chance to eat. He starts with a bowl of yogurt in the morning, then scoops peanut butter and jelly onto a bagel during a midday break and grabs trail mix by the handful upon stepping off the boat in the afternoon.

Given the choice, he would load up on pasta and bread at dinner, but the trainers have put him on a healthier diet.

"Brown rice" he says, frowning. "Quinoa."

The spray that hits crew members on the America's Cup boats is stronger than it looks. "If it's solid water," Shannon Falcone of Oracle Team USA says, "you can get knocked off your feet." (Guilain Grenier / Oracle Team USA) More photos

Around the first mark in Tuesday's race, Oracle teeters on its hydrofoils, its twin bows plunging into the sea.

This bobble sends water shooting over the deck. The crewmen have no time to duck and, with all that speed and wind, the spray feels like a blast from a fire hose.

"If it's solid water," Falcone says, "you can get knocked off your feet."

The yachts that raced in previous America's Cups were highly customized but conventional enough that an experienced amateur could steer them around the course. The AC72s are a different story.

Sailors must rely on the dizzying metrics of modern racing. Calculations flash across PDAs on their wrists and video screens built into the boat; these numbers dictate adjustments to the wing and hydrofoils.

Such complexity can make the AC72 "absolutely dangerous," says Jack Griffin, who is chronicling the races on cupexperience.com. "There is no time for ordering gin and tonics."

When AC72s capsize, they tend to "pitchpole," slamming nose-first into the water and somersaulting forward. Crewmen can get tossed into the air and bounced off the wing. They can also become trapped beneath the webbing, which happened to Simpson on the Swedish boat in May.

The incident prompted event officials to mandate more safety gear. But air tanks and sturdier helmets can do only so much.

Wind shrieks through the rigging as the boats stream across the bay. The grinders, in particular, battle cold and fatigue.

"You have a responsibility to hit your pressure," Falcone says. "You don't want Jimmy pushing the buttons and nothing happens."

The turning point in Tuesday's race occurs at the leeward mark when Oracle attempts an unconventional tack. The boat loses too much speed and Emirates zips past.

There is no time for ordering gin and tonics."— Jack Griffin, writer

Strategy is crucial on a course that zigzags about 10 nautical miles between Alcatraz Island and the shore. The catamarans crisscross at close range and sprint side by side downwind, with small decisions making all the difference.

Emirates continues to widen its lead on the third leg, moving nimbly upwind as Oracle limps home more than a minute behind, crossing the finish line adjacent to a pier where fans have gathered. Trailing four races to minus-one, the crewmen look deflated.

But, at some elemental level, the score does not matter. The challenge of trying to harness this complex new beast appeals to men who race the wind.

"These boats are so cool," Falcone says. "And we're not even close to understanding what they can do."

The sailor is looking forward to strapping on his vest and helmet Thursday morning. He cannot wait to get back out on the water.

Follow David Wharton (@LATimesWharton) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Chinese names blend tradition and drama

Picking a rare character is kind of like a marker of learning."

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.