Friends swore he’d be next Derek Jeter, but Brandon Martin is now charged in three killings

Paul Gamache saw the first body when the Corona police sergeant stepped into the two-story house with pink and yellow flowers decorating the front porch and views of the Santa Ana Mountains.

So much blood coated the man sprawled on the carpet and tile in the living room that the officer couldn’t tell his race. Somehow he was still alive. To the right, the body of a man in a workman’s uniform lay between a kitchen table and island. A clipboard with ADT security paperwork sat on the table. He was there to install a security system.

Gamache and two other officers followed a trail of blood from the first man to the three-car garage. Another body.

The men had been beaten with a black baseball bat, left in a hallway near the garage.

A name was engraved on the blood-covered wood: Brandon Martin.

Corona police had responded to the house on Winthrop Drive before the 911 call for a man not breathing on the evening of Sept. 17, 2015. Two days earlier, they were summoned after Martin, a former supplemental first-round draft pick of the Tampa Bay Rays, threatened his mother, Melody, and brother, Sean, with a pair of scissors. Sean Martin held him off with a golf club. Brandon Martin ranted that he couldn’t play baseball as long as his parents were alive.

Problems had built in the house for months. Martin, then 22, punched holes in the walls. Assaulted his father. Raced 120 mph down the 91 Freeway in his bright green BMW M3. Mumbled words no one understood. Claimed to read minds.

He struggled with alcohol and drugs. But close friends wondered if something more was behind the erratic behavior. One believed Martin was possessed. Another dreamed he drove them off a cliff.

But Martin’s parents lived in the most fear.

Simple things — the electric way he moved around the field, uncanny bat speed, a glove that vacuumed up baseballs — awed Martin’s teammates at Corona’s Santiago High. Baseball came naturally to the broad-shouldered, muscle-bound shortstop. Speed. Power. Strength. Even an inviting smile. He had everything.

“We saw his greatness at a really young age,” said a close friend who played baseball with Brandon since age 10 and spoke on the condition he not be identified because of ongoing legal proceedings. “We all wanted to be around it. We were proud to be Brandon’s friends.”

Martin was reserved and polite. Sometimes he’d play in a high-profile tournament over the weekend and his best friends wouldn’t even know about it. Baseball America noted his “quiet personality” in a glowing scouting report. Coaches encouraged Martin to be more of a leader. But that wasn’t him.

“You can’t even fathom what that money does to an 18-year-old mind.”

— Justin Hayes, a former clubhouse attendant for the Inland Empire 66ers

The tight-knit group of friends noticed quirks. He needed Skittles before each game, one friend recalled. They weren’t optional, even if getting them made Martin late. He wasn’t one to show up to practice early or stay late. He grew silent if someone tried to coach him, coming off as if he already knew it all.

Still, friends swore he would be the next Derek Jeter. The Rays gave him $860,000 to sign with them in June 2011 after drafting him 38th overall. Martin promised friends he’d take care of them and bought a black Nissan Titan for his father. But the reality of professional baseball quickly became apparent during his first season with the rookie-level Rays team in Florida.

“The pitching out here is ridic!” Martin texted a childhood friend in Corona in July 2011, using shorthand for “ridiculous.”

The commitment to the game extended to the tattoo on Martin’s right arm: a large pitchfork with the middle spike piercing a baseball.

Tired of living with his parents, Martin rented a mansion in Yorba Linda for $6,000 a month in late 2011. The 6,700-square-foot marble-filled home on Hidden Hills Road included a spiral staircase and sprawling views from virtually every window.

“You can’t even fathom what that money does to an 18-year-old mind,” said Justin Hayes, a former clubhouse attendant for the Inland Empire 66ers who was one of Martin’s roommates and his closest friend.

Between November 2011 and February 2012, the Brea Police Department responded to at least 19 calls at the residence. Police records mention repeated loud parties, a brawl with baseball bats and “blood everywhere,” subjects urinating on nearby lawns, someone brandishing a black airsoft rifle, underage drinking.

During a New Year’s party responsible for several of the calls, Martin threw $2,012 in one-dollar bills off a balcony. So many people jammed the mansion that Hayes couldn’t see the floor. Someone filmed a music video. Police reported an open fire in the backyard and guests running in the street.

Friends called this “Brandon’s house.” He liked that.

“Things got a bit out of hand in that house,” said Matt Budgell, a former minor league pitcher for the New York Mets who lived there. “We were doing cocaine, drinking all the time. ... We tried coke for the first time together. Then it was more coke, more coke for him. I think it might’ve been a necessity thing. You keep doing it long enough and coke is not enough. You want to get higher.”

Another longtime friend since Little League noticed the drug affected Martin differently than others who used it.

“If he did coke, he looked like a crazy animal,” the friend said. “Eyes wide, like a Tasmanian devil.”

The nickname started as a joke.

Friends noticed subtle changes in Martin the following offseason when the entourage rented a more modest home, this time with five bedrooms and views of the Eagle Glen Golf Club in Corona. The parties continued. But Martin was different, even after a season that led Baseball America to name him the best defensive infielder in the Rays organization.

He spent more time in his room playing video games like Call of Duty. He seemed on edge. He mumbled to himself. He laughed for no reason. His eyes looked vacant. He responded to questions with one-word answers, his voice often so low no one could understand it.

He was a stranger. So they called him George.

In an instant, Martin could flip from the joke-cracking kid who always picked up the tab for rent, tattoos or lunch to George, the aggressive, confrontational stranger.

His friends were baffled. Some blamed the drug use. Others faulted an emotional breakup with a girlfriend. Everyone wanted to be around Martin at the Yorba Linda mansion. Now friends drifted away.

“He would get to be a whole other person and really didn’t understand how the world was really working,” Hayes said. “He didn’t understand what was going on.”

One day that winter, Martin and a couple of old friends smoked pot and tossed a baseball around at El Cerrito Sports Park in Corona. When someone mentioned Martin’s hitting problems the previous season, he asked if this meant the friends were against him. He grabbed a bat from the trunk of a car. He wanted to fight.

The friends tried to calm Martin. They repeatedly apologized. They went home shocked, wondering what happened to their childhood friend.

Late in 2013, Hayes and Martin parked at a Chevron station on Yorba Linda Boulevard.

Martin told his friend to stop laughing at him. Hayes had no idea what he was talking about.

“I can hear your thoughts,” Martin said.

He was serious.

He was so not there that it was almost like talking to an empty soul. I regret that we didn’t view it as being mentally unstable.

— A longtime friend said of Martin's behavior

When Martin visited Oregon State with his family for a football game in November 2013, according to a pending civil lawsuit in Riverside County Superior Court, he was “agitated and erratic” and made repeated comments about drugs. The lawsuit said Martin failed a test for

Two months later, Martin joined a group of friends at a timeshare in Las Vegas. He left the next day without a word and flew to Florida for the Rays’ annual winter development camp. Martin and a coach got into a heated argument after the prospect removed his cleats early. The Rays sent him home.

More than two dozen Rays teammates, managers, coaches, clubhouse staff, even the scout who signed him, either declined to comment or didn’t respond to interview requests.

The lawsuit said Martin could return to the Rays if he apologized and sought help. He didn’t seem to grasp that his career was in jeopardy.

“He was so not there that it was almost like talking to an empty soul,” one longtime friend said. “I regret that we didn’t view it as being mentally unstable. We viewed it as a druggie being a druggie.”

The son’s yelling woke the parents.

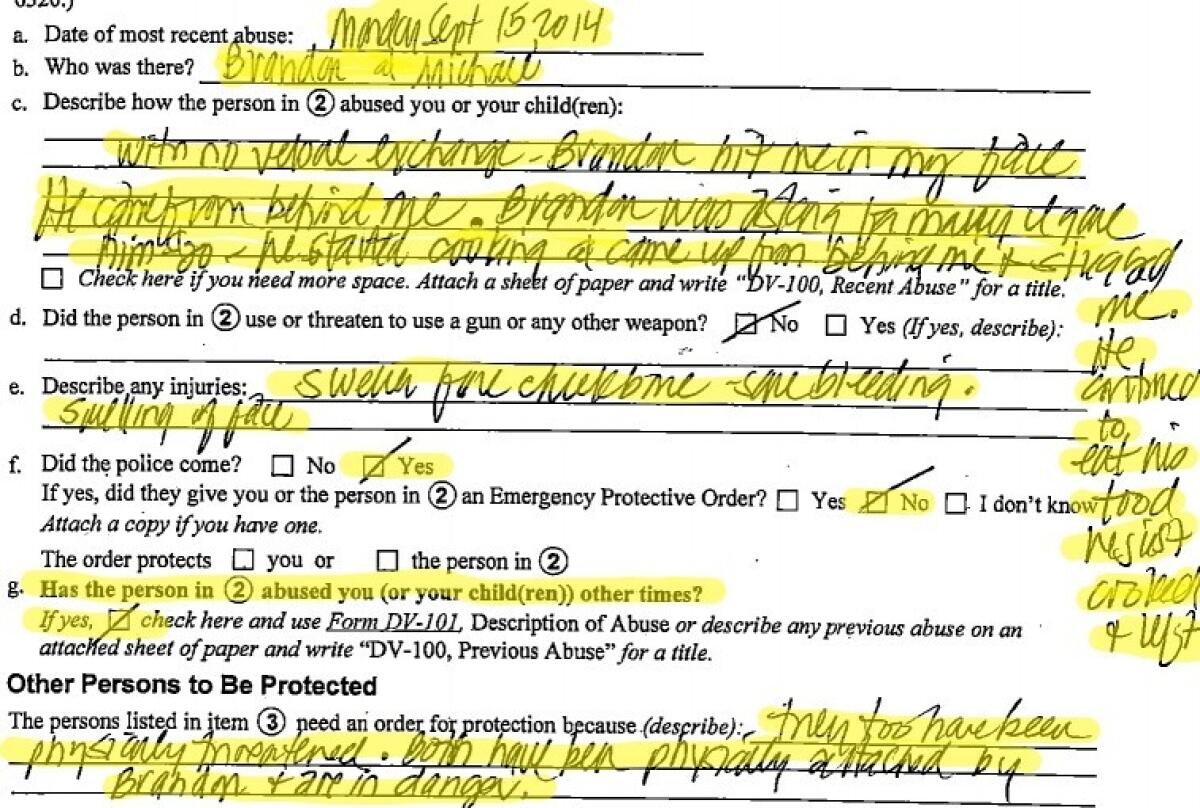

Michael and Melody Martin ventured downstairs in their home around 1 a.m. in February 2014. According to an application for a restraining order, Brandon Martin, who left the Eagle Glen house and resumed living with his parents, put his mother in a headlock and cut one of his father’s fingers by pulling on it. No one called the police.

On Sept. 15, 2014, the application said, Martin punched his father in the face without a word, then asked for money. Michael Martin handed over $20. The son sat down to eat as if nothing had happened.

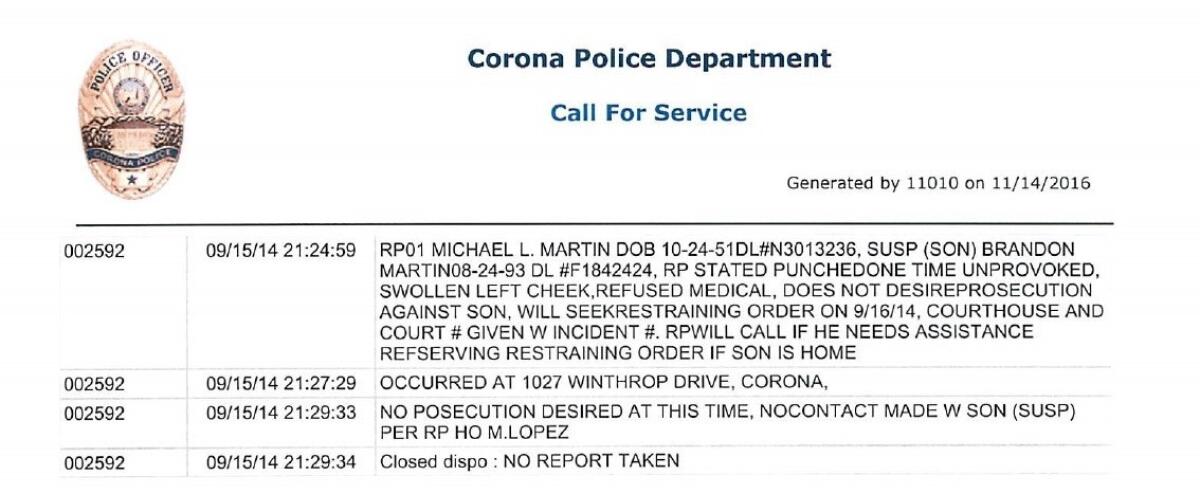

Michael Lopez, the responding Corona police officer, noted the incident in the department’s call log: “Unprovoked, swollen left cheek, refused medical, does not desire prosecution against son.”

The parents sought a restraining order — they wrote on the application they were in danger — and wanted their son ordered to move out. A judge dismissed the action three weeks later when the parents didn’t appear in court.

The night of the alleged assault, John Sommers noticed Martin at the end of a hallway in a Corona hotel. They were on and off friends since eighth grade. Sommers was part of the group at the Eagle Glen house. They fell out over $30,000 Martin invested in a business deal Sommers arranged.

In the hallway, Martin bragged about hitting his father in the face. He laughed. He found the incident hilarious.

Martin stopped working out, stopped throwing, stopped visiting batting cages. The Rays released him in March 2015. He hadn’t played in a game for more than a year.

He briefly camped in his parents’ backyard and stole from them, the lawsuit said. Police were called at least three times, including once when Michael Martin believed his son stole his truck. During a trip to the beach, Budgell told Martin to follow a white car to the correct exit. Martin, whose driving grew more erratic each day, insisted white cars covered the road. They didn’t.

“It would be like a switch would flip and he would be a completely different person,” said Hayes, who thought it was mental issues, not drug use. “His rational thinking was just not there. His conscience went away.”

In April 2015, Budgell saw Martin for the last time. He rubbed his arms and scratched his chest. He couldn’t stop moving.

“He looked like I could break him in half with my fingers if I had to,” Budgell said. “He looked like a druggie. He lost himself.”

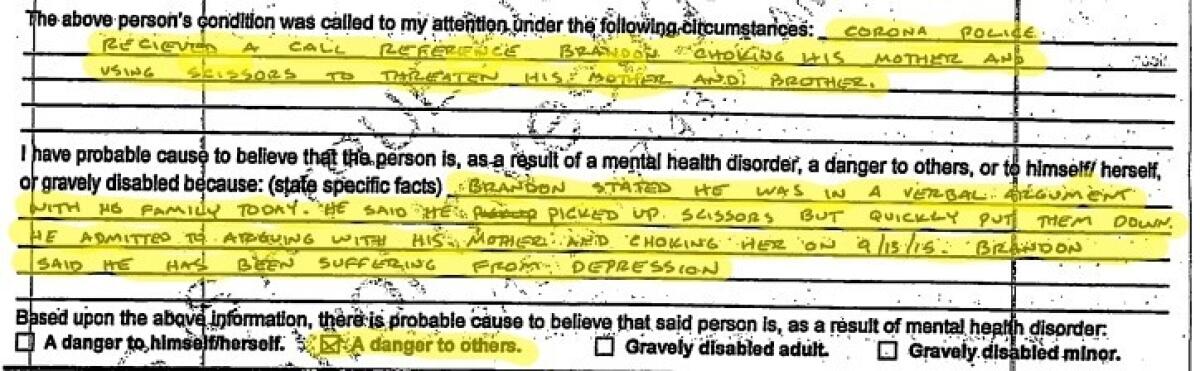

Corona Police Officer Edgardo Sandoval responded to the Martin home on Sept. 15, 2015, after Martin threatened his mother with scissors.

Stanley Andersen, one of Martin’s uncles, joined the family at the home. He believed the son and mother argued over his appointment with a therapist.

“Stanley stated Brandon often acts aggressively towards family when he becomes upset,” Sandoval wrote in the incident report. “Stanley feared for the safety of Brandon’s parents because he felt neither one had the physical ability to defend themselves against Brandon if he becomes aggressive again.”

The officer coaxed Martin onto the front porch. Martin admitted to the scissors incident and said he choked his mother two days earlier, as well. Martin said he was depressed and feared for his safety after she slapped his shoulder. He called it self-defense. The incident left his mother’s neck swollen and bruised for several days.

In a declaration, Sandoval later described Martin’s behavior and explanations as “bizarre and inappropriate.” The officer handcuffed Martin. He didn’t resist.

Sandoval wrote in the report that Michael Martin wanted his son left at home and Sean Martin, who played football at Oregon State, didn’t want his brother detained because “it would ruin his life.”

The lawsuit alleged several family members were “upset and scared” Brandon Martin wasn’t arrested.

Sandoval took him a half-hour away to the Riverside County Regional Medical Center’s psychiatric facility on a mental-health hold for up to 72 hours.

The officer checked a box on the detention application: “A danger to others.”

Martin’s stay at the drab building on County Farm road lasted less than two days.

He was admitted for assessment at 8:55 p.m. on Sept. 15, then transferred to a nine-bed unit in the inpatient psychiatric hospital at 11:28 p.m. the next day after multiple evaluations.

On Sept. 17, Dr. Debbie Ann Imperial Rosario, the attending psychiatrist, diagnosed Martin with a mood disorder in addition to marijuana and alcohol abuse during a 75-minute meeting. She noted features of “antisocial, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders.”

The facility discharged Martin at 1:23 p.m.

“Brandon no longer met the criteria for ongoing involuntary detention,” the doctor said in a declaration.

According to the lawsuit, Melody Martin and another family member pleaded with hospital staff not to release Brandon. The doctor said she wasn’t told the mother didn’t want her son to return. The mother had already arranged for a security system to be installed at the home.

Her son received a bus pass home.

Three men waited at the house on Winthrop Drive that afternoon. Michael Martin. His brother-in-law, Ricky Andersen, stopped by to protect him in case Brandon Martin returned. A local contractor, Barry Swanson, wrapped up installing the security system.

Andersen planned to give Brandon an ultimatum, court records said. Enroll in a Salvation Army rehabilitation program for six months or move out within the hour. Around 6 p.m., Andersen spoke to his son, Mike, on the phone. Brandon refused to leave.

The line went dead.

Mike Andersen called back. Nothing. He drove to the house and found the front door unlocked. He called 911 at 6:35 p.m.

Michael Martin, 64, and Swanson, 62, were pronounced dead at the scene. Ricky Andersen, 58, died two days later. They had all been struck in the head.

The men’s cellphones and wallets were missing. So was Swanson’s white Ford F-150 Raptor.

The next morning an officer in an unmarked Corona police car spotted the Raptor. Other officers joined the chase. They tried to ram the truck’s rear quarter panel twice as it wound through side streets, blew through multiple stop signs and a red light. On the third try, after the truck briefly drove into oncoming traffic, the maneuver finally disabled the truck a half-mile from Winthrop Drive.

Brandon Martin, wearing a black T-shirt and tan pants, ditched the truck and hopped a fence. His sandals remained on the street.

He sprinted through backyards, broke into a home on Derby Street as a woman showered in the master bedroom, then he tumbled out a second-story window. His Anaheim Angels cap fell off in the room.

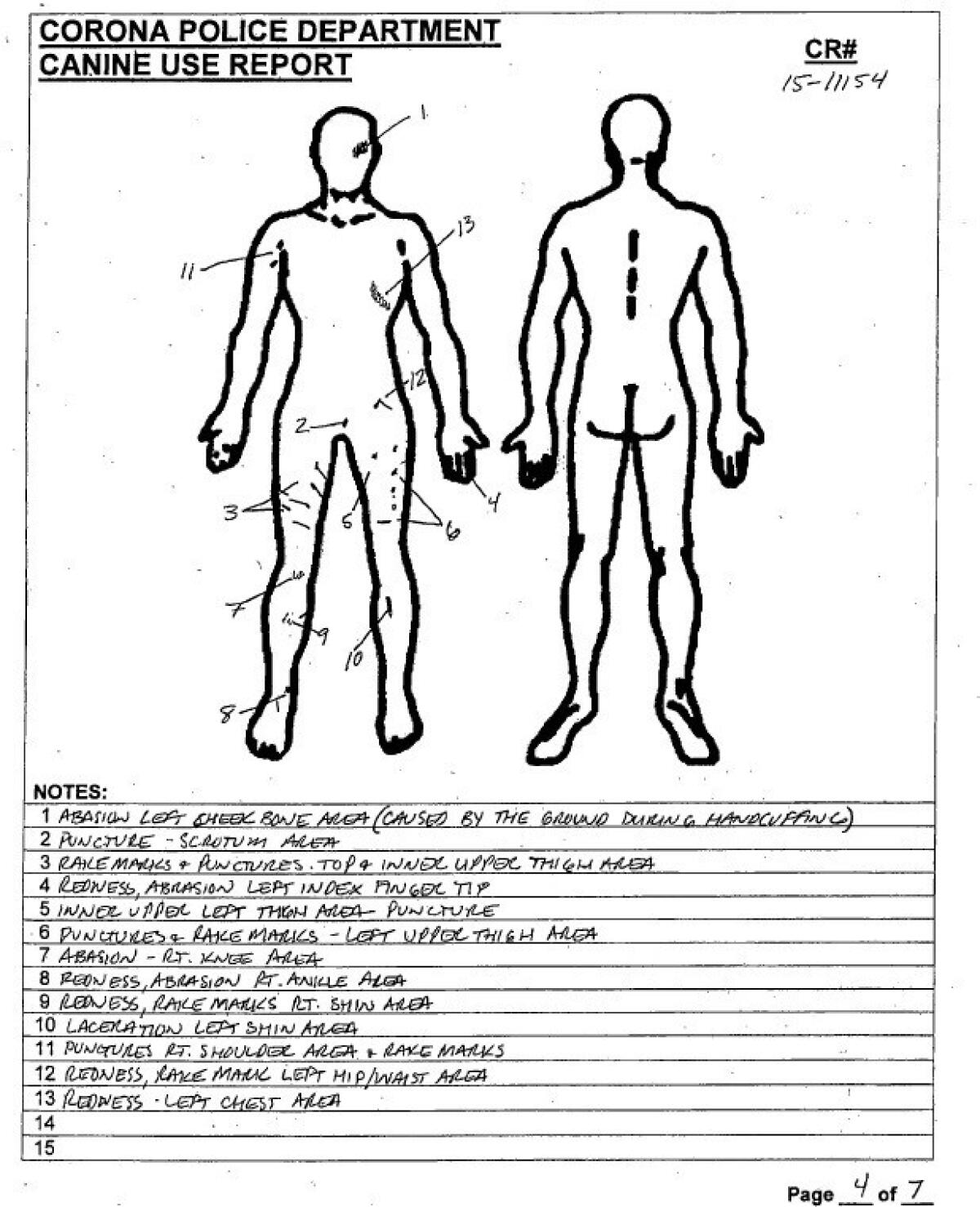

Officers advanced with guns drawn. Martin lay on his back without moving. He didn’t respond to commands to show his right hand. An officer released a dog, a Belgian Malinois named Dex. The K9 bit Martin’s left leg. He sprung to life and repeatedly punched the dog, the handler’s report said. Martin picked up the 79-pound animal and body-slammed him onto the concrete patio. The dog yelped, but continued to bite Martin’s inner thigh and pierced his scrotum.

Fearing Martin had a weapon concealed in his waistband, one officer kicked him twice, then jabbed his AR-15 muzzle into Martin’s temple twice. At least four other officers joined in subduing Martin with baton blows, punches and kicks.

“He struggled up until the very end, until the handcuffs were on,” Cpl. Jeff Bennett testified during Martin’s preliminary hearing last year.

An officer found the truck key and 33 cents in Martin’s pockets.

Four days later, Martin gave Corona Police Det. Gail Gottfried two versions of what happened when questioned about the killings, according to court testimony.

In both stories, Martin denied any involvement. After discovering the bodies, he told the detective, he didn’t call family members or police. Instead, he rummaged through the men’s pockets, grabbed their cellphones, then drove the Raptor to Carl’s Jr. to eat.

The friends second-guess themselves. They replay conversations, missed opportunities, warning signs. They wonder how baseball and money and potential descended into this hellish reality. They wonder if they could’ve intervened earlier and prevented the deaths.

“There was always that thought in my mind that something could happen,” Hayes said. “But I never would’ve thought …”

He trailed off.

The Andersen, Martin and Swanson families sued Riverside County last year — the lawsuits were consolidated into one case — alleging the hospital didn’t properly treat Martin. The county denied their claims. An attorney representing the Andersen and Swanson families declined comment because the case is ongoing.

Melody Martin declined an interview request. Brandon Martin and his defense team didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Martin pleaded not guilty to three counts of murder and several related charges. Judge Bambi J. Moyer found him mentally competent to stand trial last year. His attorneys recently told the court they would be ready for trial by September. Prosecutors intend to seek the death penalty.

The one-time prospect spends his days in the seven-story Robert Presley Detention Center in downtown Riverside. Inmate No. 201537233, like the rest of them, gets a 12x12 box for personal belongings. Dayrooms open outside cells at 7 a.m. for inmates to read, watch television or participate in programs to learn landscaping or construction skills. They visit the recreation yard for about three hours each week and are allowed two outside visitors every seven days.

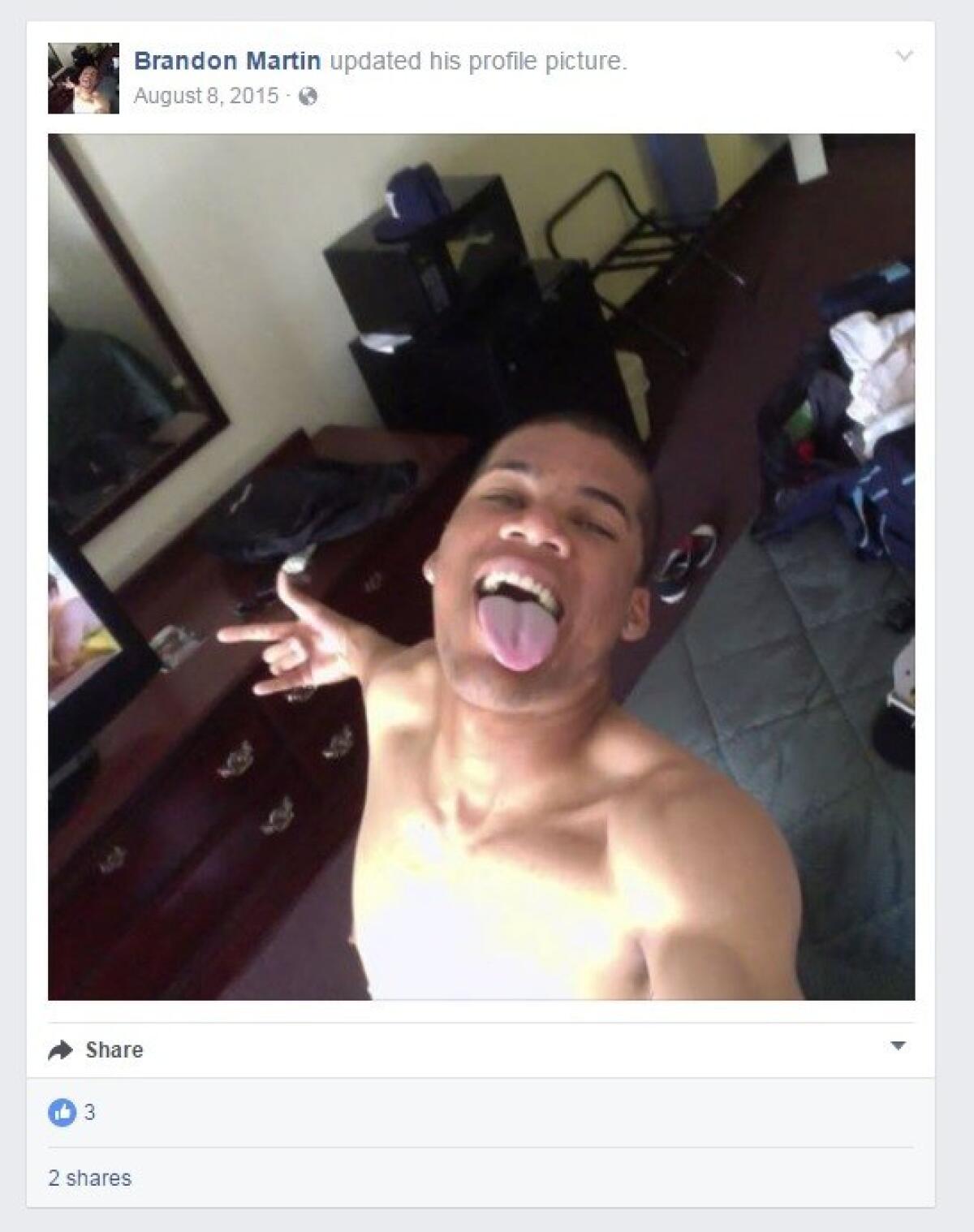

A selfie Martin posted a few weeks before the killings remains on his Facebook page. He appears to be in a hotel room, shirt off, staring at the camera with his tongue out and eyes half-closed. Old friends still stumble across the photo. But they don’t see Brandon. They see a stranger.

Follow Nathan Fenno on Twitter @nathanfenno

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.