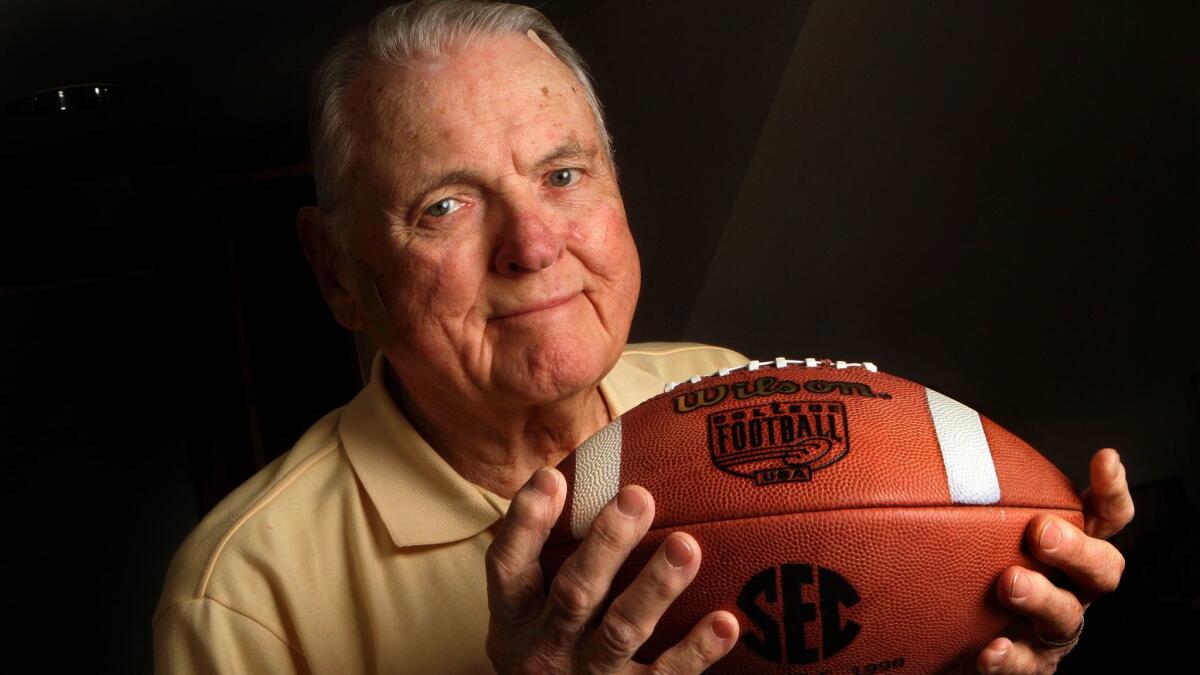

Keith Jackson, folksy voice of college football, dies at 89

For decades during college football season, his homespun phrases moved across the airwaves.

Linemen were not guards and tackles, they were “the big uglies.” Running backs didn’t drop the ball, there was a “fuumm-bull!” Of an undersized player, he might say, “He’s a little-bitty thing, a bantam rooster. But he’s young. If he keeps eatin’ his cornbread, he’ll be man-sized someday.”

And, of course, there was “Whoa, Nellie!,” which became known as his signature phrase.

Keith Jackson, the folksy voice of college football who for decades weaved backwoods wit through ABC broadcasts, died Friday night. He was 89.

The longtime Sherman Oaks resident worked 15 Rose Bowls, more than any other announcer. No cause of death or other details were given in a statement from ESPN, which, along with ABC, Jackson’s longtime employer, is owned by the Walt Disney Co.

Though Jackson described many of college football’s greatest moments, he had a special connection with the Rose Bowl. It was Jackson who came up with the Rose Bowl moniker, “The Granddaddy of Them All.”

“Whoa, Nellie!” was another matter. Strangers in restaurants, airports, stadium parking lots and downtown streets would sidle up to Jackson and bellow the phrase. However, Jackson always maintained that he might have — might have, mind you — used the phrase a time or two early in his career but that it mostly was the work of impersonators, primarily Roy Firestone, who were responsible for its spread.

“This ‘Whoa, Nellie!’ thing is overrated,” Jackson said frequently. “There were all kinds of stories going around. People said I had a mule in Georgia named Nellie. Well, we had a mule in Georgia, but her name was Pearl.”

Despite his protests, Jackson enthusiastically proclaimed “Whoa, Nellie!” in a beer commercial late in his career.

So entrenched in college football was he that ABC wouldn’t let him retire the first time he tried. He announced before the 1998 season that it would be his last, that, at 70, he was tired of getting on airplanes. But he was back in the booth in the fall of ’99, the network having lured him with a promise of keeping him close to his Sherman Oaks home by restricting his assignments to the Pacific time zone. He finally called it a career after working the Texas-USC national championship game at the Rose Bowl in early 2006.

Jackson lived in the same home, at the end of a cul-de-sac on a quiet Sherman Oaks street, for some 50 years. The sprawling, east-facing deck off the back of the house, where Jackson loved to sip red wine with his wife, Turi Ann, offered views of the San Fernando Valley that, on a clear day, stretched all the way to the Rose Bowl.

Jackson was formally honored in 2015 when the Rose Bowl’s radio and television booths were renamed “The Keith Jackson Broadcast Center.” He attended his final Rose Bowl at the end of the 2016 season and was interviewed on air after halftime of the USC-Penn State game.

“He was a John Wayne type — he told his old war stories, and it was priceless, because it was Keith Jackson,” said Darryl Dunn, the Rose Bowl general manager who grew close to Jackson over the last 10 years.

“We were very blessed that we got to know Keith personally, and what people saw on air and on TV was exactly who he was. He talked to you like he was in your living room with you. That’s who he was, a really nice person from Georgia who had a passion for college football and telling stories.”

Outside the broadcast booth, one of Jackson’s passions was golf. He became a member of the Los Angeles Country Club in 1980 and was a regular golfing partner of celebrities such as Bob Hope and Vin Scully.

At his best, Jackson told Golf Digest, he was probably a four handicap. He was good enough to play in the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic in 2009, at age 80.

Before being slowed by some health issues in recent years, Jackson golfed at least three times a week, often with his wife, and shot a 78 at age 80 on the L.A. Country Club’s exceedingly difficult North Course.

“I’ve walked through the club with him, and it was always, ‘Hey, Keith,’ and ‘How ya doing, Keith?’ ” said Harvey Hyde, a former college football coach and current radio broadcaster who was close to Jackson.

“Everybody recognized him. He was as big as anyone there, because when his face came on the screen on Saturday, you knew he had the biggest game of the weekend. He was the A-team.”

If Jackson was highly regarded by viewers and listeners — and he was — he was at least equally respected by many coaches.

“He’s my hero,” former Iowa coach Hayden Fry once told the Associated Press. “He stands for all the good things associated with college football.” Added Joe Paterno, the late Penn State coach: “Keith Jackson and college football. You can’t say one without the other.”

Jackson was born Oct. 18, 1928, in Carrollton, Ga., about 50 miles west of Atlanta, not far from the Georgia-Alabama border. He practiced broadcasting as a youngster growing up on a farm there — “My grandma once told my mama, ‘The kid’s walking crazy around the cornfield, talking to himself.’ I was calling ballgames.” — but it wasn’t until he was in college that he saw it as a possible career. And, at that, he sort of fell into it.

By then, it was the early 1950s. Jackson, after graduating from Georgia’s Roopville High School, where he played on a championship basketball team, had served a four-year overseas stint in the Marine Corps and was attending Washington State in Pullman, Wash., on the GI Bill, studying criminology and political science. The school had its own radio station, and as Jackson listened to a student broadcast of a football game, he thought, “I can do better than that.”

He said as much to the professor in charge of the broadcasting program, was handed a tape recorder and told to go cover something. He chose a basketball game at Pullman High as his first assignment. “They turned the lights out at halftime,” he recalled for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1999. “I didn’t have the foggiest idea what to do, so I just told stories.”

Whatever he did impressed the professor, and the world lost a budding criminologist, gaining a future sports broadcasting legend. By 1952, Jackson was calling Cougars games on the school station. After graduating in 1954, he went to work at KOMO-TV, a new ABC affiliate in Seattle, combining sports and news broadcasting.

His proudest achievement there was accompanying the University of Washington rowing crew to Moscow, where he did the first live sports broadcast from the then-Soviet Union, despite serious hassles over equipment, censorship and accessibility to the event site. Afterward, local journalists told him he’d been lucky, that contemporaries who’d tried to buck the Soviet system had disappeared.

Jackson joined the ABC radio network in 1965, freelancing TV assignments before settling in permanently at ABC when Roone Arledge needed someone to call a parachute-jumping segment for “Wide World of Sports” in 1968.

ABC quickly put him on college football, and the fit, as Jackson might have said, was “pert-near” perfect. After announcing his retirement in 1998, he was honored wherever he went to work games. At Michigan, former coach Bo Schembechler presented Jackson with an autographed helmet and a Michigan jersey at halftime while the marching band spelled out, “THANKS KEITH.”

Jackson had his opinions on developments in the sport that he loved — he favored a playoff system over the postseason bowl system, for instance — but on the air, he kept them to himself, concentrating on the action. His broadcasting philosophy was a simple one: “Amplify, clarify and punctuate, and let the viewer draw his or her own conclusion.”

“If I’ve helped people enjoy the telecast, that’s fine,” he insisted. “That’s my purpose.”

He was roundly criticized — unfairly, he said — for ignoring an ugly incident late in the 1978 Gator Bowl game, when Ohio State coach Woody Hayes punched Clemson player Charlie Bauman after Bauman had intercepted a pass near the Ohio State sideline.

Recalling the scene for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1999, Jackson said that because the sideline was crowded with players and officials, “the fact of the matter is, I didn’t see [the punch]. ... If people go back and listen, I said, ‘Let’s look at the tape and see what happened.’ But we didn’t see the tape because the network was nickel-and-diming the operation at that time with a bunch of green kids and the tape was in New York, which did not feed to us in the booth. I saw [the punch] for the first time at noon the next day on NBC.”

Jackson rose above that incident, later winning an Emmy and being inducted into two sportscasting halls of fame. Besides college football, he worked college and pro basketball games, Major League Baseball, auto racing, Summer and Winter Olympics and, in 1970, was the first play-by-play announcer for NFL’s “Monday Night Football” on ABC.

It was college football, though, that set him apart. As Paterno said, “You always know it’s a big game when Keith is there.”

While at Washington State, Jackson married another student, Turi Ann Johnsen. She survives him, as do their children, Melanie Ann, Lindsey and Christopher, and grandchildren.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer; DiGiovanna is a staff writer.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.