KITAHIROSHIMA, Japan — Shohei Ohtani is watching over his former team.

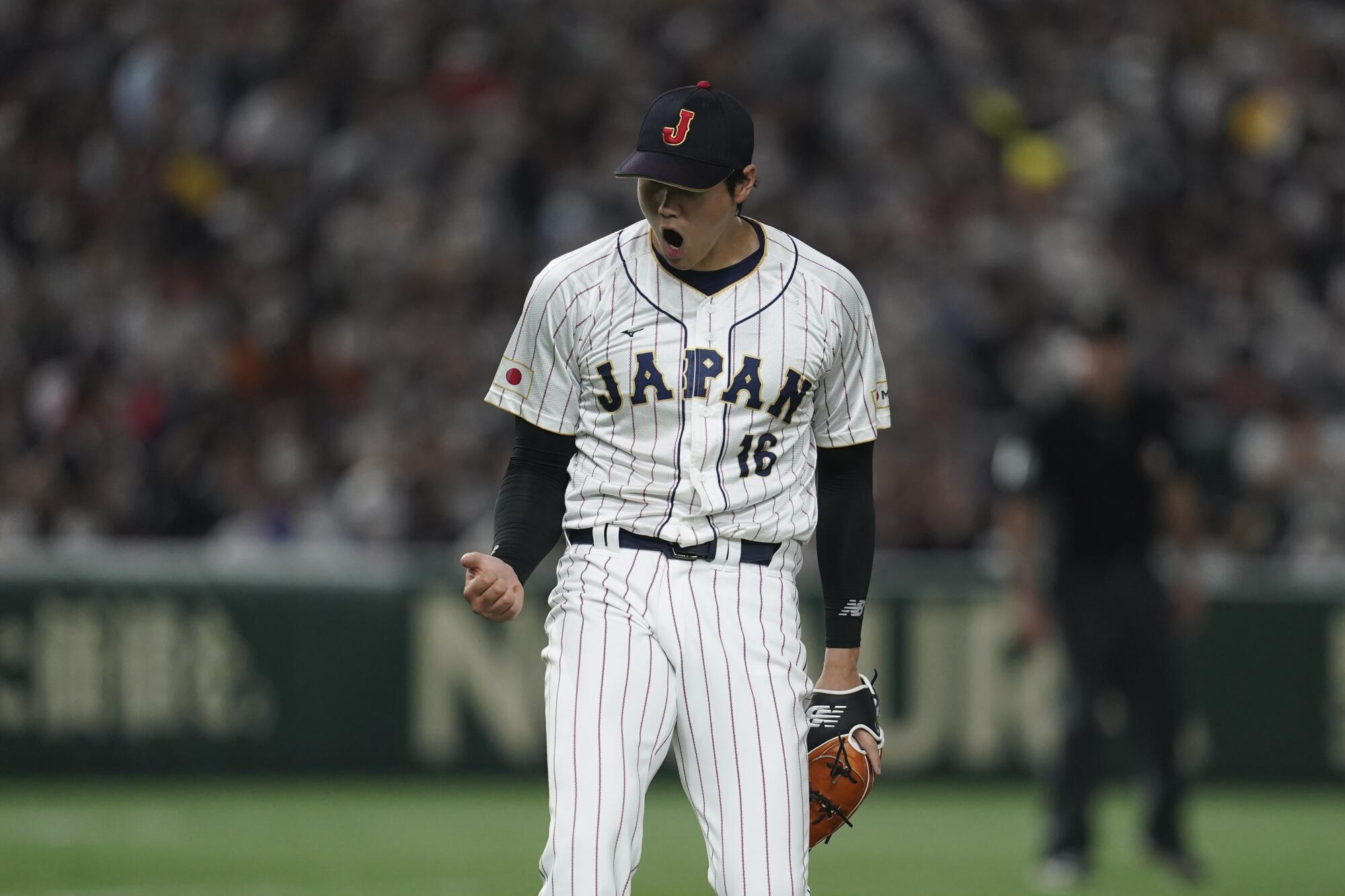

Behind the left-field wall at Es Con Field Hokkaido, on the other side of the visiting bullpen, beyond three rows of seats and a concourse, there is a wall painting that measures approximately 22 feet wide and 18 feet high.

Depicted on the left side of the mural is Yu Darvish, the San Diego Padres right-hander who pitched for the Nippon-Ham Fighters for seven years. On the other side is Ohtani, who replaced him as their franchise player.

Pictures are taken here by visitors every day, if not during games, on guided tours of the stadium.

More than six years after leaving the Fighters to pursue his major league ambitions, this is what Ohtani has become.

A painting on a wall.

A myth.

Shohei Ohtani’s stardom has made an immediate impact among Dodgers players and staff, who marvel at the level of attention the team is receiving.

The two-way player whom Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido once claimed as its own is now “a being above the clouds,” according to longtime Fighters broadcaster Shinji Daito.

“He no longer represents Hokkaido,” Daito said in Japanese. “He represents all Japanese people.”

This is the responsibility, and opportunity, the Dodgers inherited when they signed Ohtani to a heavily-deferred 10-year, $700-million contract this winter.

The Dodgers will have a chance to bring the wall painting to life.

They will open their season next week in South Korea, and team officials believe the Dodgers also will be chosen to start their 2025 campaign in Japan, according to people familiar with their thinking unauthorized to speak publicly.

The planned series is expected to be played at the Tokyo Dome, but the new home of Ohtani’s former team could host a couple of exhibition games in the preceding days, according to people with knowledge of the plans.

Theoretically, the Dodgers could visit the Fighters at Es Con Field for those games, which would mark Ohtani’s return to Hokkaido.

Fighters infielder Gosuke Katoh imagined what that would be like, considering Ohtani’s place in Japanese society.

“He’s on the front page of every sports newspaper every single day,” Katoh said. “With his $700-million contract, people say he’s not worth it. The playing side, we don’t know what’s going to happen in 10 years. But from a financial standpoint, if you live in Japan for just one week and look at every single sports paper every day, you’ll understand why he’s worth that money.”

The Fighters feel they have a stadium worthy of a world-class event.

“I keep telling everyone that this is probably the best stadium in the world,” said Katoh, who played a handful of games for the Toronto Blue Jays and experienced Fenway Park in Boston and Minute Maid Park in Houston.

“This is better than the vast majority of big league ballparks,” said outfielder Andrew Stevenson, another former major leaguer. “The only thing I’ve seen come close to it is the Rangers’ new place” — Globe Life Field.

The retractable-roof, 35,000-seat stadium in Hokkaido opened last year and is the Fighters’ signature achievement in the post-Ohtani era. From a financial standpoint, it‘s a stretch to call this “The House That Ohtani Built,” as the posting fee the Fighters received for Ohtani’s rights from the Angels in 2017 covered only $20 million of the estimated $500 million it cost to build. But from a spiritual standpoint, the nickname could be considered applicable, as the Fighters approached constructing the stadium with the same mind-set they had when developing Ohtani as a two-way player.

Shohei Ohtani is no Muhammad Ali when it comes to talking about himself, but his standout play and his legions of fans have made him a social media star.

“Everyone here thought about building a stadium that’s never been built before,” Fighters corporate officer Ken Iwamoto said.

The batter’s eye is the backside of a craft brewery. The wall on the outfield side of the stadium is 230 feet high and made of glass, which helps the growth of the grass playing surface.

The mural of Ohtani and Darvish is part of the facade on Tower 11, which is a tribute to the uniform number they both wore for the Fighters. The five-story building includes hotel rooms, a hot springs-style bath and sauna.

Es Con Field shares a common architect with Globe Life Field — U.S.-based HKS.

“I like to say it’s kind of like a spring-training facility as our home ballpark,” Katoh said. “The weight room is massive. It’s kind of like a spring-training weight room. Spring-training weight rooms are made for 200-plus people. We have it for 28 guys. The cafeteria is massive.”

As breathtaking as the stadium is, the venture is viewed as a risk. The team’s previous home was a city-owned, multipurpose dome stadium in Hokkaido’s capital of Sapporo, which has a population of almost 2 million. Es Con Field is in Kitahiroshima, which is about a 40-minute drive from Sapporo and has fewer than 60,000 residents.

Success ultimately will depend on the development of a ballpark village named F Village, for which plans include housing, a medical campus and train station. At the moment there’s not much on the 40-minute walk from the nearest train stop to the stadium.

Daito, who has called Fighters games on Television Hokkaido for the last 20 years, compared the project to the team’s plan to develop Ohtani as a two-way player.

“No one thought the Fighters would leave Sapporo,” Daito said.

The broadcaster recalled how Ohtani didn’t always enjoy the widespread support he does now, even in his home country. If anything, many were offended by Ohtani’s insistence on pitching and hitting.

“I think there were some fears that if Ohtani succeeded in becoming a two-way player, it wouldn’t reflect well on Japanese baseball,” Daito said. “Everyone starts as an ace and No. 4 hitter. But as you climb the ranks, your place in the game starts to shrink. That’s normal. That’s evidence that you’re playing at a high level.”

These stories have become legends in these parts, feeling almost as if they happened a lifetime ago or somewhere else. To that point, Ohtani has played longer in the major leagues than he did for the Fighters.

When Ohtani played his final season in Japan, in 2017, his jersey was everywhere in the Sapporo Dome on game days. These days there are virtually none, with fans opting for the shirts of the next generation of Fighters. Many wear replicas of manager Tsuyoshi Shinjo’s No. 1 jersey, of which there is a variation that reads across the back, “Big Boss” — Shinjo’s self-given nickname.

“Ohtani of the Angels and Ohtani of the WBC had such a strong impact,” Daito said, they overwhelmed the memories of Ohtani of the Fighters.

Shohei Ohtani, baseball’s top free agent, agrees to a $700-million deal with the Dodgers. Here’s everything you need to know about Ohtani joining the Dodgers.

However, as someone who has watched Ohtani on every step of his journey to global stardom, Daito spoke of how proud he was that Ohtani continues to play with an obvious enjoyment of the game.

“He does things that make the world think of Japanese people in a way that we want to be thought of,” Daito said. “Let’s say he was a great athlete who would do absolutely anything to make money. We wouldn’t want him to represent us. That kind of person might be admired in the United States or other parts of the Americas, but there has to be a spiritual component, a mental component, to gain the respect of Japanese people.”

The scale of what Ohtani has accomplished, as well as what he represents, has made the locals here feel as if he’s a distant figure. A couple of exhibition games could make them feel as if he’s theirs again.

The Fighters are ready to make that happen. The Dodgers are too.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.