The most important 15 minutes of the day happen hours before first pitch.

That’s when, home or road, day or night, opposing ace or patchwork bullpen game awaiting them on the mound, every member of the Dodgers lineup will gather in the batting cages near their clubhouse.

They’ll sit in a group, study-session style.

And they’ll start to talk — about that game’s pitcher, about their plan of attack and about how to raise the bar for baseball’s best offense a little higher.

Hitters’ meetings like this are standard around baseball, a daily staple of life in the majors.

What’s different with the Dodgers is the way they go about it.

Every day, it’s the players who talk first — and, often, the most.

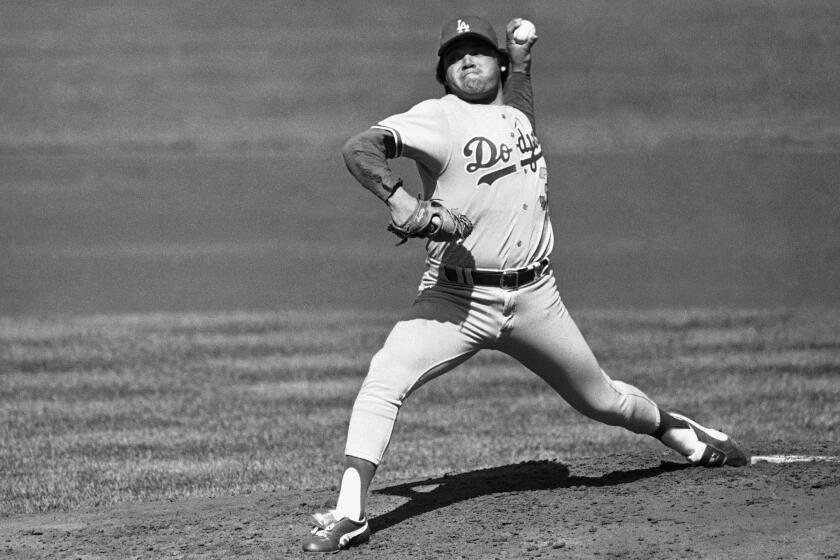

Julio Urías has had a stellar season for the Dodgers and he deserves to be in the conversation with Miami’s Sandy Alcantara for the NL Cy Young award.

Each right-handed hitter will explain their past experiences against a particular pitcher, their expectations for that night’s at-bats and what they plan to do when they step in the box.

The left-handed hitters will do the same.

The team’s three hitting coaches will wait until the end, making sure the conversation stays on the right track, and offering suggestions where they see fit, but not interfering with what has become the most collaborative effort most hitters in the Dodgers’ star-studded lineup say they’ve ever experienced.

“They’re letting it be player-led,” Justin Turner said.

“It holds everyone accountable, if we’re all talking about something,” Max Muncy added.

“It’s a group, a collective effort,” said Freddie Freeman. “I just feel like it’s been such a great process over the course of the year.”

It has certainly been reflected in the results.

The Dodgers led the majors in scoring at 5.23 runs per game. Since the 1950s, only once has a Dodgers team scored more over a full season, and that was in 2019 when the baseballs were juiced.

And though they’ve cooled off in recent weeks since clinching the division, they still finished first in the majors in on-base-plus-slugging percentage (.775), third in walk-to-strikeout ratio and fourth in batting average (.257).

They knew they’d have talent this year, with Mookie Betts healthy again, Trea Turner embarking on his first full season with the team, and Freeman joining the mix as a $162-million offseason signing.

But they never could have imagined the bonds that have developed behind the scenes, a cross-lineup cooperative that has been — and, they hope, will continue to be this October — at the core of an offensive juggernaut.

“This is my seventh year with this ballclub,” manager Dave Roberts said, “and this is the most communication that they’ve had internally amongst players.”

There are differing origin stories as to when the Dodgers evolved into the majors’ most devastating lineup.

For the first two months of the season, they sped past opponents sometimes, but too often sputtered through frustrating quiet spells as well.

By mid-June, they were fifth in runs, but closer to league average in batting average, home runs and, most notably, hitting with runners in scoring position — an underwhelming start for one of the most expensive lineups in the majors.

“At that point, it wasn’t good,” Roberts said, recalling a series sweep against the San Francisco Giants in which the Dodgers scored four runs and went two for 24 with runners in scoring position. “It wasn’t team baseball. There was no urgency.”

“Team baseball” can be an abstract idea in a sport defined by individuality in each hitter’s swing, and predicated on individual battles in every at-bat.

And for a new-look Dodgers roster, it took even more time to figure out exactly what was missing.

Freeman was brand new, in the process of changing organizations for the first time in his career. Trea Turner had only been with the Dodgers for the final two months of 2021, returning this year for his first full season with the organization. Even Betts had never experienced a truly normal season in Los Angeles, after his first two campaigns with the Dodgers were clouded by the pandemic.

Along with such veterans as Justin Turner and Muncy, they were the biggest voices in the room. But, 65 games into the season, they still weren’t fully clicking, still not consistently operating on the same wavelength.

“Offense just doesn’t take talented players to score,” Roberts said. “It just doesn’t happen like that.”

How it all changed is where their memories diverge.

Roberts recalled a hitter’s meeting in Cincinnati, before a three-game sweep against the Reds in which the Dodgers scored 26 runs and took a lead in the NL West standings they wouldn’t relinquish.

The Dodgers have put together the greatest regular season in franchise history, so they need to accept the World Series expectations that come with it.

“Guys were kind of saying the right things,” Roberts said. “It was good to see that the players themselves took it upon themselves to right the ship.”

Players recall the transformation being more subtle. Betts said there was a particular hitter’s meeting that stood out, in which “we had a little talk on focusing on winning,” but couldn’t remember exactly when.

Freeman failed to pinpoint any one moment, instead noticing a slower shift in mentality — and communication — among the group as the summer progressed.

“It’s been a running thing, reiterating what we’re trying to practice and our approach and game plan,” Freeman said. “Because sometimes in this game, you get so self-absorbed about what your swing is doing, this and that. Sometimes, you just gotta look external.”

Once the Dodgers’ hitters started getting on the same page, it didn’t take long for the results to follow.

There was a midseason change in early July, when the top three hitters in the lineup brainstormed a new batting order in which Trea Turner followed Betts in the leadoff spot, with Freeman batting third.

“It’s certainly hard to quantify, but I know the value of it,” Roberts said. “When you see three of your best players, having conversations about the order, the pitcher, team offense, everyone follows.”

There was a new routine in the dugout, a Freeman-suggested rule in which the team limited itself to two digital tablets on the bench during games, redirecting more of their attention to the action on the field and less on analyzing their swings between every trip to the plate.

“This game is so analytically driven now and so iPady that, we’re trying to get eyes up,” Freeman said. “There’s a lot of stuff you can learn from watching the game every single pitch. And over the course of the year, it’s gotten so good.”

And, of course, there was the organic transformation of their hitters meetings, with hitting coaches Brant Brown and Robert van Scoyoc, as well as assistant Aaron Bates, allowing the hitters to strategize among themselves before every game.

“I think Rob and Browny and Bates have done a good job of going around the room individually, talking to guys, and then we have our meetings, going around to every guy and having those conversations,” Justin Turner said. “I don’t want to say they’re making them verbalize what they want to do, but they’re letting it be player-led.”

Justin Turner said in years past, the Dodgers usually only had a handful of players who would speak up in meetings. Rarely would they all share their exact game plans prior to first pitch.

The benefit of the new system?

“There’s a lot of accountability to verbalizing what you’re seeing, what you’re thinking,” he said.

He then offered an example.

My son is 53. He’s a baseball fan. He has Down syndrome. To him, baseball is more than a game.

“If a guy goes up and swings at an 0-and-0 curveball, you can just come back and say, ‘Oh, I was sitting on it,’ ” Turner said. “When you say it in the meeting — ‘Hey, I’m gonna look for 0-and-0 spin and put a good swing on it’ — and then you do it in the game, even if you roll over on it, all the guys are like, ‘Hey man, good try. You executed your plan.’ ”

It becomes especially true whenever runners are in scoring position, where the Dodgers now lead the majors in average and OPS, a key catalyst behind their historic performance at the plate.

“You can see it, guys are giving up at-bats to move guys over and get guys in and do the right things,” Muncy said. “It’s what’s made our offense so good.”

It was a day like so many others for the Dodgers this year.

The only difference was the opponent.

Before a start against 2021 National League Cy Young Award winner Corbin Burnes in late August, Dodgers hitters walked into the batting cages pregame and were greeted by nearby TVs, each one flashing film of their previous performance against the Milwaukee Brewers right-hander from a week prior.

When they sat down for their pregame meetings, the hitters talked through their individual approaches, then came to agreement on a broader team game plan, deciding they needed to attack earlier in the count than they had in the prior matchup.

That night, they went out and executed to a tee, ambushing Burnes for seven runs over four innings in what became one of the best displays of their talent-rich lineup, and cohesive behind-the-scenes system, working as intended.

“Sometimes you just forget to hang out with your teammates and talk,” Freeman said. “I think the thing that got us going, was the communication between us.”

Come the start of the division series next week, it’s what the Dodgers hope will continue to fuel their offense, as well.

The club has seen talented lineups falter in October before, with past teams becoming suddenly susceptible to a rash of strikeouts and untimely hitting once the intensity of the playoffs — and caliber of opponent — begins to kick in.

It’s part of the reason why, despite winning 100-plus games in three of the last four full-length regular seasons, and finishing with a top-five scoring offense four years running, they’ve won only one World Series in recent memory. A lack of playoff offense has often been a familiar theme.

They believe this year’s team is built to be different, however, buttressed by the foundational pillars built on and off the field over the winningest season in franchise history.

“If you try to do everything yourself [all year], then you try to lean on someone in October, that doesn’t work,” Freeman said, creating a hugging motion with his arms during a recent interview. “When you are leaning on someone on June 19, it creates an environment where we’re doing this as a whole and not just stuck in an iPad looking, looking, looking. You have to build it.”

Brown, in his fourth year helping run the offense, referenced the slogan the Dodgers printed across the back of their pregame workout T-shirts this year.

“Nine is one,” he said. “One is none.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.