Column: Dodger Stadium wedding shows progress team has made in LGBTQ community

Erik Braverman will march down an aisle leading out of the Dodgers’ dugout.

Jonathan Cottrell will march down an aisle leading out of the visitors’ dugout.

Together they will meet on the pitching mound in front of about 80 family members and close friends to engage in an ancient ritual, on ancient soil, in a moment of great enlightenment.

Braverman, a Dodgers senior vice president, and Cottrell, a software engineer, are officially uniting on Jan. 21 in one of the crown jewels of what was once the most intolerant of sports.

The two men are getting married at Dodger Stadium.

“Hopefully this will show that in a sport like baseball, even if you don’t feel you fit in, you can always find a place,” said Braverman, senior vice president of marketing, communications and broadcasting.

Pitcher Max Scherzer clears the air on how the Dodgers utilized him in the playoffs, saying it didn’t lead to him signing with the Mets.

Dodger Stadium has been Braverman’s place since he joined the organization in 2008. It became a cornerstone for him when he came out publicly as gay in 2015 and felt the full support of a Guggenheim ownership group determined to repair a longtime fractured relationship with the local LGBTQ community.

“Dodger Stadium is a place I called home for 15 years, a place I publicly came out, a place where I witnessed some amazing games, but a place I’ve never been able to utilize for myself,” said Braverman. “I approached Lon [Rosen, Dodgers’ executive vice president/chief marketing officer] and said, ‘I want this for my wedding, but does this seem selfish?’”

Rosen’s response struck to the heart of a Dodgers front-office culture that has emphasized inclusiveness.

“I think it would be perfect,” Rosen told him.

Perfect it is, in so many ways, a wedding for two guys who once would be outcasts in this old-school sport but are now using baseball as the backdrop for the most important moment of their lives.

“Dodgers and gay wedding … Dodgers and gay wedding … that’s what you’ll see in every photo … this will be a constant reminder of how sports have changed.”

— Cyd Zeigler, co-founder of Outsports.com

“Getting married in front of anybody takes guts, but to do it at the cathedral at Chavez Ravine?” said Billy Bean, a gay former Dodger who is an MLB vice president and special assistant to the commissioner. “This is a transparent example of the environment Dodger ownership has created for the people who work there. This doesn’t happen at every stadium.”

The vows will be made on the pitcher’s mound. Their names will be emblazoned on the videoboards. The guests will be seated on the field around them. The reception will be in the bar in the left-field pavilion. Some music will be played by organist Dieter Ruehle.

Yes, guests will receive a bobblehead doll featuring the couple holding hands. Yes, the guests are encouraged to wear a hint of blue. And yes, absolutely, there will be Dodger Dogs.

“You can’t have an event at Dodger Stadium without Dodger Dogs, can you?” said Braverman.

It is not only about the marriage of Braverman and Cottrell, but also about the marriage of baseball and the LGBTQ community, an event that will produce images that will resonate long after the rice has been thrown.

“Baseball is metaphorically and physically wrapping its arms around this wedding,” said Cyd Zeigler, co-founder of Outsports.com. “Dodgers and gay wedding … Dodgers and gay wedding … that’s what you’ll see in every photo … this will be a constant reminder of how sports have changed.”

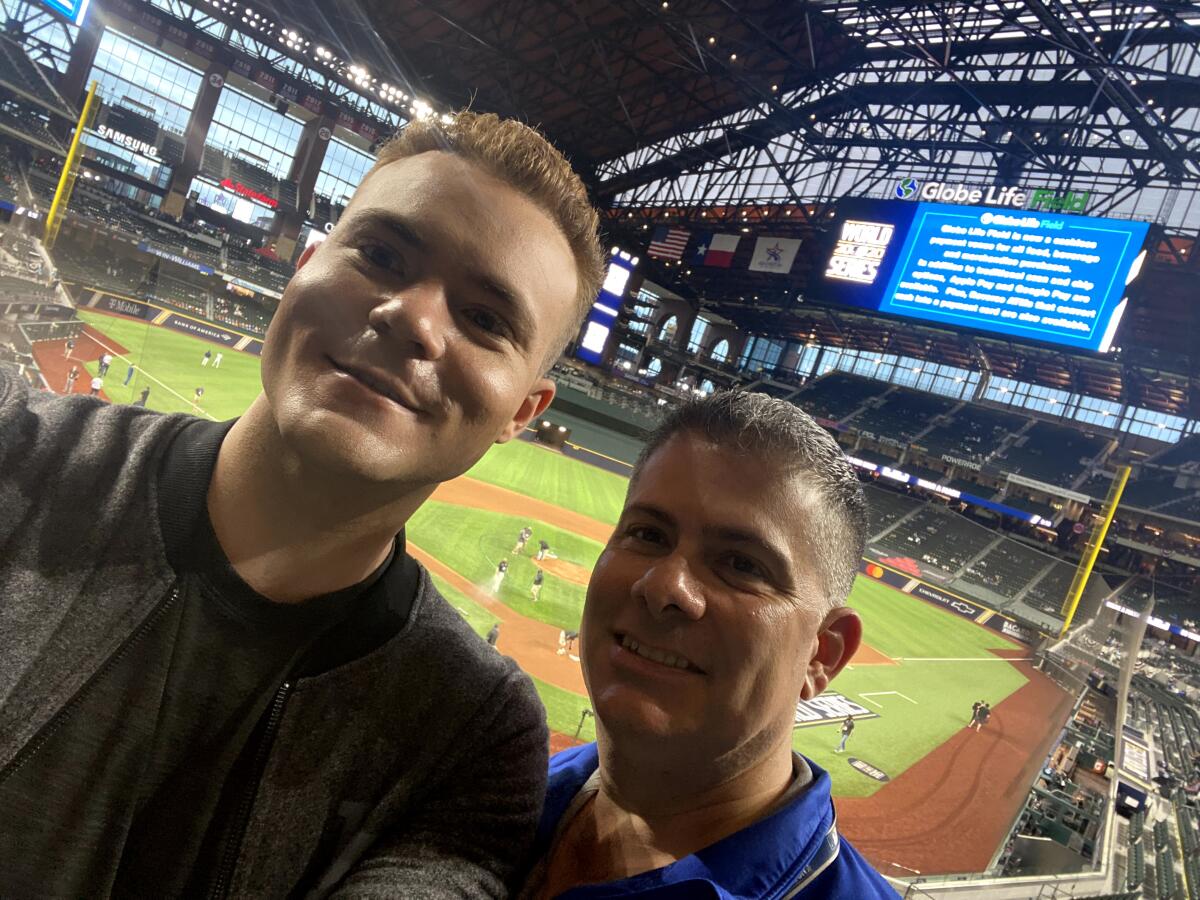

New Dodgers infielder Eddy Alvarez won silver medals in speedskating at the 2014 Winter Olympics, and in baseball at the Tokyo Olympics.

It will also be a constant reminder of how the Dodgers have changed since Guggenheim purchased the team in 2012. The organization previously had a fractured relationship with the LGBTQ community. Today its leaders say Rosen’s direction has changed that.

“There were things that happened in the history of the Dodgers, and we wanted to make sure the LGBTQ community knew we embraced them, and embraced all communities,” said Rosen. “I mean, these are our fans.”

This is the organization that once shunned gay outfielder Glenn Burke, trading him to Oakland in 1978 after he allegedly refused then-general manager Al Campanis’ monetary offer to marry a woman. A year earlier, Burke and teammate Dusty Baker were credited with inventing the high-five.

This is also the organization that once ejected Danielle Goldey and Meredith Kott from a game in 2000 because they were kissing in the stands. The organization later apologized and donated 5,000 tickets to gay rights groups, but the damage had been done.

This, too, is the organization of Tommy Lasorda Jr., who came out as gay and died in 1991 at age 33 of complications from AIDS. He was the son of celebrated manager Tom Lasorda, yet his father never acknowledged his son’s sexuality, and repeatedly denied that he had succumbed to AIDS complications despite the death certificate stating otherwise.

Much has changed with the Dodgers since then, beginning with Guggenheim’s focus on a revived Pride Night. The first time Rosen scheduled one in September 2013, several Dodgers players grumbled, and some even refused to take the field during pregame ceremonies. The Dodgers ignored their complaints and have since turned the annual affair into a rollicking party.

“It’s the biggest, most robust Pride Night in all of professional sports, period. Nothing comes close,” said Zeigler. “There is no team in professional sports that is more welcoming or embraces the community on a year-round basis more than the Dodgers.”

Their commitment to the community was strengthened in 2015 when Braverman became one of sport’s highest-ranking officials to publicly come out as gay.

“I’ve always prided myself in being the guy behind the scenes, I never wanted to be the spotlight kind of guy, and in talking to Lon and Stan [Kasten, club president], I asked them, ‘What does it serve me to come out, why would I do this?’” recalled Braverman. “They said it isn’t for you, it’s for everyone.”

Braverman now counsels folks in similar situations throughout the sports world as the Dodgers continue to include and diversify.

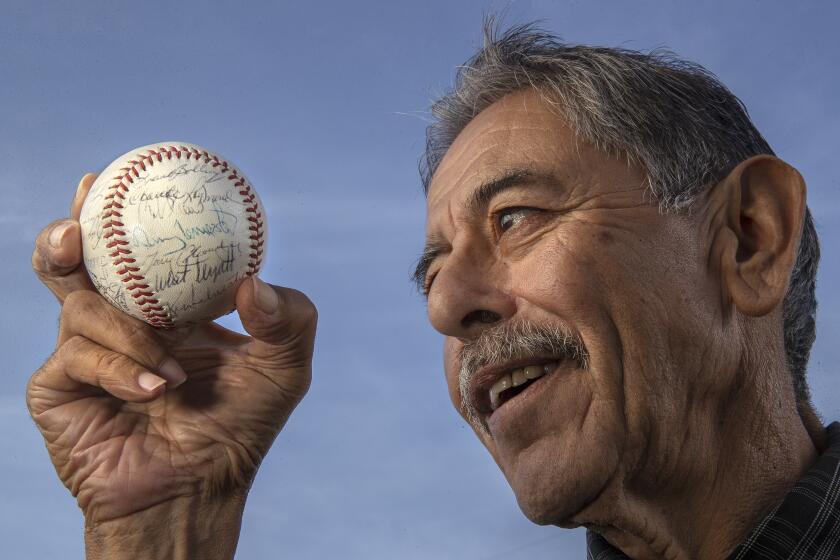

Denny Lemaster was a pitching phenom at Oxnard High who became a big leaguer. Buddy Salinas had a baseball signed by him in 1963 that he felt compelled to return.

Two of their co-owners are Billie Jean King and Ilana Kloss, who are married. They also embrace co-owner Magic Johnson’s son EJ, a television personality who has come out as gay.

“None of this is a surprise,” said Zeigler. “It’s just all part of the Dodgers legacy.”

The Dodgers’ family will soon grow by one with the inclusion of Cottrell, whom Braverman met three years ago in a swimming pool in Mexico.

Braverman, 51, was smitten.

“I was attracted immediately to him physically, of course, but beyond that, to his intellect and his ability to fit into any and all situations,” he said.

Cottrell, 31, fell in love with the look.

“Erik’s big brown eyes that always have a glint of mischief and his smooth radio voice drew me in immediately,” he said.

Together they sent out wedding invitations that look like a ticket stub. Together, they will tie the knot in a ceremony that will end with the sounds of “I Love L.A.”

No surprise there. The Dodgers play that song after every win.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.