Fifty years ago, Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale engaged in a salary holdout that would help change baseball forever

Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax, actor David Janssen and Dodger pitcher Don Drysdale sit on the set of a movie for a news conference in 1966 when Koufax and Drysdale were holding out for better contracts from the Dodgers.

Fifty years ago this week, Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale reported to spring training. The rest of the Dodgers had already been there for a month.

The best pitchers on the defending World Series champions were widely viewed as heretics in the context of their time. There was no free agency, no salary arbitration, and no power in the players’ union.

If a player did not like the salary dictated by management, he could stay home. So Koufax and Drysdale did, threatening by their absence to turn the Dodgers from the best team in the National League into an also-ran.

In the end, the pitchers got more money. The Dodgers got back to the World Series. The fans adored their heroes once again.

Within a decade, Marvin Miller had organized baseball’s players into what would become the most powerful union in American sports, breaking free of rules that bound them to their team until the team let them go.

But Miller did not start his job until Koufax and Drysdale were in the second week of their holdout, an event often overlooked in the chronicles of baseball’s labor history.

“We’ve come a very long way,” Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw said. “We owe a lot to our former players that fought for our rights.”

When Kershaw signed for $215 million two years ago, he chose to stay with the Dodgers. Koufax had no choice. The Dodgers aces past and present have become close, and Kershaw was not surprised to learn that the best pitcher in baseball had been willing to retire if necessary, and had stood up for himself before his union could stand up for him.

“He’s the type of guy who knows what’s right and would fight for it,” Kershaw said.

::

It was Feb. 23, 1966, and The Times splashed the headline across the top of the page: “Koufax, Drysdale Eye $1 Million Pact.”

That would be a paltry sum for a player today, when the average major league salary is almost $4 million, but such riches were unheard of 50 years ago. In 1965, Koufax won 26 games and his second Cy Young Award in three years. He finished second to Willie Mays for the National League most-valuable-player award.

The Dodgers paid Koufax $85,000 that season. They paid $80,000 to Drysdale, who won 23 games, batted .300 with seven home runs, and finished fifth in the MVP race.

For 1966, the Dodgers offered $100,000 to Koufax and $85,000 to Drysdale. The San Francisco Giants had signed Mays for two years, at about $125,000 per year.

Koufax and Drysdale, wary of the Dodgers’ playing one pitcher against the other, teamed up and asked for three years at a total of $1 million — split equally, so that each would earn $167,000 per year. And they told the Dodgers to talk to their agent, akin to a sin at the time.

The duo effectively became baseball’s first union — a union of two.

“No one, to my knowledge, had ever thought about two pitchers teaming up,” said Vin Scully, the voice of the Dodgers then and now.

And what would the Dodgers have been without Koufax and Drysdale?

We would not have won without them.

— Maury Wills

“Nothing,” shortstop Maury Wills said. “We would not have won without them.”

In Florida, the Dodgers went about the business of spring training. At one point, general manager Buzzie Bavasi gathered photographers as he jokingly knelt and prayed in front of the large pictures of Koufax and Drysdale hanging above the entrance to the team offices.

In California, Koufax and Drysdale gathered photographers too, at Paramount Studios, as they signed a deal to appear in a movie called “Warning Shot” — Koufax as a detective, Drysdale as a television commentator. They later agreed to appear on a television variety show called “The Hollywood Palace.”

“Don is expected to sing with his own guitar accompaniment,” a show spokesman told The Times. “Koufax will concentrate on humor.”

As the holdout lingered and the season approached, Scully said, fans took consolation in the absurdity of the Dodgers fielding a team without Koufax and Drysdale.

“In the back of their minds, they thought, ‘It has to end, they’re not going to play without those two,’” Scully said. “That would seem preposterous.”

But public opinion — and media coverage — was not on the side of the pitchers. The Times’ initial report on the salary dispute tagged Koufax and Drysdale as “the flinging financiers” pursuing “their double-barreled raid on the Dodger treasury.”

A March 15, 1966 Times report from spring training called the holdout “the greatest player revolt in the 77-year history of the Dodgers” — ignoring or forgetting the heated objections among several Brooklyn players to sharing a clubhouse with Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier.

Koufax declined an interview for this story. In his 1966 autobiography, he said he was discouraged by the reception he and Drysdale got from a large segment of the fan base during the holdout.

“It was astonishing to me,” Koufax wrote, “to learn that there were a remarkably large number of American citizens who truly did not believe we had the moral right to quit rather than work at a salary we felt — rightly or wrongly — to be less than we deserved. . . . Just take what the nice man wants to give you, get into your uniform, and go a fast 25 laps around the field.”

::

When the Dodgers opened camp in 1966, Koufax and Drysdale were not the only stars holding out. So was Wills, who had finished third in the NL MVP race — one spot behind Koufax, two spots ahead of Drysdale.

That holdout ended quickly, in a meeting between Wills and Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley. With Koufax and Drysdale holding out too, O’Malley had seen more than enough.

“Mr. O’Malley scared me to death, saying I was in cahoots with them,” Wills said. “He said, ‘They might be able to get away with that, but you can’t.’

“I got a ticket right away and went to spring training. He put a contract in front of me and I signed it. I didn’t even look at it.”

That kind of episode was not unusual at the time, said Dick Moss, the first general counsel for the players’ union under Miller. Players skilled in hitting or pitching were not permitted to employ an agent skilled in negotiation.

“They had to go in and talk to the general manager about their contracts, alone,” Moss said.

Players at the time were told they were lucky... If it wasn’t for baseball, they’d be driving trucks. Or, if they were black, they were told they would probably be picking cotton.

— Dick Moss, the first general counsel for the players’ union

“Players at the time were told they were lucky to be playing baseball. If it wasn’t for baseball, they’d be driving trucks. Or, if they were black, they were told they would probably be picking cotton. It was a very primitive time.”

Dollars aside, Koufax was ardent in his belief that players should be allowed to be represented by agents, and that an arbitration process should be available to resolve salary disputes.

Under the so-called “reserve clause” in effect at the time, a player was bound to his team for as long as the team liked, with no recourse other than retirement. A player could not threaten to leave for another team.

“The best agent in the world couldn’t alter the built-in advantage the reserve clause gives the club,” Koufax wrote. “I was under the impression that everybody in this country is entitled to representation.”

In a 1967 first-person account in Sports Illustrated, Bavasi explained why he resisted the concept of player representation.

“If I gave in and began negotiating baseball contracts through an agent, then I set a precedent that’s going to bring awful pain to general managers for years to come,” Bavasi wrote, “because every salary negotiation with every humpty-dumpty fourth-string catcher is going to run into months of dickering.”

During the holdout, Bavasi emphasized he would talk with the agent representing Koufax and Drysdale but would negotiate only with the players.

“Big mistake,” said Peter O’Malley, who followed his father in running the Dodgers. Walter O’Malley died in 1979.

Peter O’Malley said his father said privately that players, like management, ought to be entitled to qualified representation. O’Malley also said some of Bavasi’s more glib comments might have inflamed the situation, hardening positions and ultimately prolonging the holdout.

It never should have happened.

— Peter O’Malley, former Dodgers owner

“It never should have happened,” O’Malley said.

::

On March 30, 1966, as the Dodgers flew west from Florida, the team plane erupted in applause. Koufax and Drysdale had signed.

Koufax got $125,000. Drysdale got $110,000.

“They were worth every penny they got, and more,” Wills said.

Bavasi was less than thrilled.

“When the smoke had cleared, they stood together on the battlefield with $235,000 between them,” Bavasi wrote, “and I stood there with a blood-stained cash box.”

Bavasi, who died in 2008, wrote that the holdout “gimmick” had worked only because Koufax might have been the greatest pitcher of all time.

“Be sure to stick around for the fun the next time somebody tries that gimmick,” Bavasi wrote. “I don’t care if the whole infield comes in as a package; the next year the whole infield will be wondering what it is doing playing for the Nankai Hawks.”

That became the most enduring legacy of the holdout, but not in the way Bavasi had intended.

Two years later, as Miller and Moss negotiated their first collective bargaining agreement, owners wanted protection against players teaming up to hold out.

That was historic, and new, and troublesome to a lot of people in the industry.

— Peter O’Malley

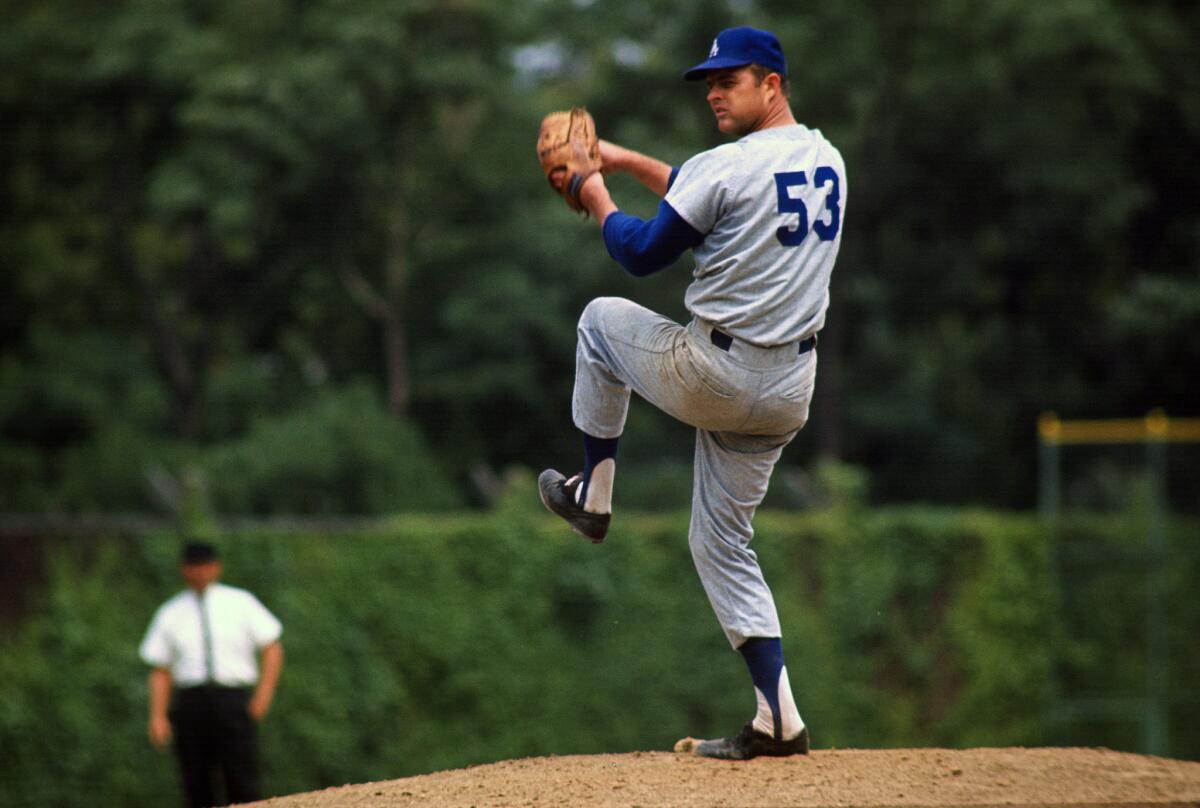

Dodgers pitcher Don Drysdale winds up his delivery against the Pittsburgh Pirates during a game at Forbes Field in 1965.

“That was historic, and new, and troublesome to a lot of people in the industry,” Peter O’Malley said. “If two of your four starting pitchers can do that, why can’t your starting outfield do it?”

The union’s response, according to Moss: We’ll be happy to agree that players cannot act in concert with one another, so long as the owners agree to the same thing.

The owners did, signing off on the language that two decades later would be used to cite them for collusion in depressing free-agent salaries. In 1990, the owners agreed to settle by paying the players $280 million.

“It came back to bite them,” Moss said.

In the aftermath of the holdout, Koufax and Drysdale were not viewed as winners. They were not welcome to employ an agent. They did not split the salary difference with the Dodgers. They settled for less. They signed contracts for one year, not three — although Koufax already had decided to retire after the 1966 season.

And, in that 1966 autobiography, Koufax made an admission that appears naive in hindsight.

“We were not out to break the reserve clause; we were trying to find a way to live more comfortably inside it,” he wrote. “I think baseball needs the reserve clause; I don’t see how it could remain competitive without it.”

That was the prevailing view at the time, said Donald Fehr, who joined the union in 1977 and succeeded Miller as its leader in 1985. Fehr stepped down in 2009 and became executive director of the National Hockey League players’ union in 2010.

As baseball’s owners waged a fierce but ultimately unsuccessful fight to keep free agency out of the sport, they warned that the richest teams would buy up all the best players. Bowie Kuhn, the commissioner from 1969-84, admonished players that some teams would go bankrupt, and that the American League might even go out of business.

The apocalypse never came to pass.

In the 15 years preceding the holdout, the New York Yankees won the World Series seven times, the Dodgers four times. In the past 15 years, 10 teams have won the World Series, none more than three times.

The major leagues have expanded to 30 teams, up from 20 at the time of the holdout and 24 at the advent of free agency. The average player salary has jumped from $50,000 at the start of free agency to almost $4 million last season.

None of those riches found their way to Koufax or Drysdale, who died in 1993. They might have been the most dynamic pitching duo in baseball at the time, but they took a risk in bucking the system in a way no one ever had.

It took a lot of courage, a lot of guts and a lot of determination to stand up and to do it in a quiet, dignified manner.

— Donald Fehr, MLB players’ union leader from 1985-2009

“It took a lot of courage, a lot of guts and a lot of determination to stand up and to do it in a quiet, dignified manner,” Fehr said. “And the impression that they left on players was that, if you do that, you can actually achieve success. You’re not complete pawns. There are things you can do.

“I think that message — sometimes overtly discussed, most of the time in the background — was one of the things which was changing players’ minds as Marvin came in. They began to organize. They began to educate players. They began to talk about the system.”

Within a decade, Miller led the players on strike, and led a union charge that resulted in the abolition of the reserve clause and the introduction of salary arbitration and free agency. The players most often associated with the charge were Curt Flood, who unsuccessfully challenged the reserve clause in the Supreme Court, and Andy Messersmith, granted free agency by an arbitrator who ruled the reserve clause should not be perpetual.

Fehr recalled that Miller often said the “first key event” in the players’ assertion of labor rights ought not to be credited to the union.

Koufax and Drysdale deserved the credit.

“In terms of the development and enhancement of players’ rights, in the modern era, this was the first shot out of the cannon,” Fehr said. “And it was done without Marvin and the union. The guys did it themselves.”

Twitter: @BillShaikin

ALSO

Dodgers channel price cut gets tepid response

Justin Turner grand slam pushes Dodgers past Rangers, 5-4

Dodgers pitcher Jamey Wright calls it a career, and a quirky career it was

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.