Maury Wills has the law on his side in Hall of Fame bid

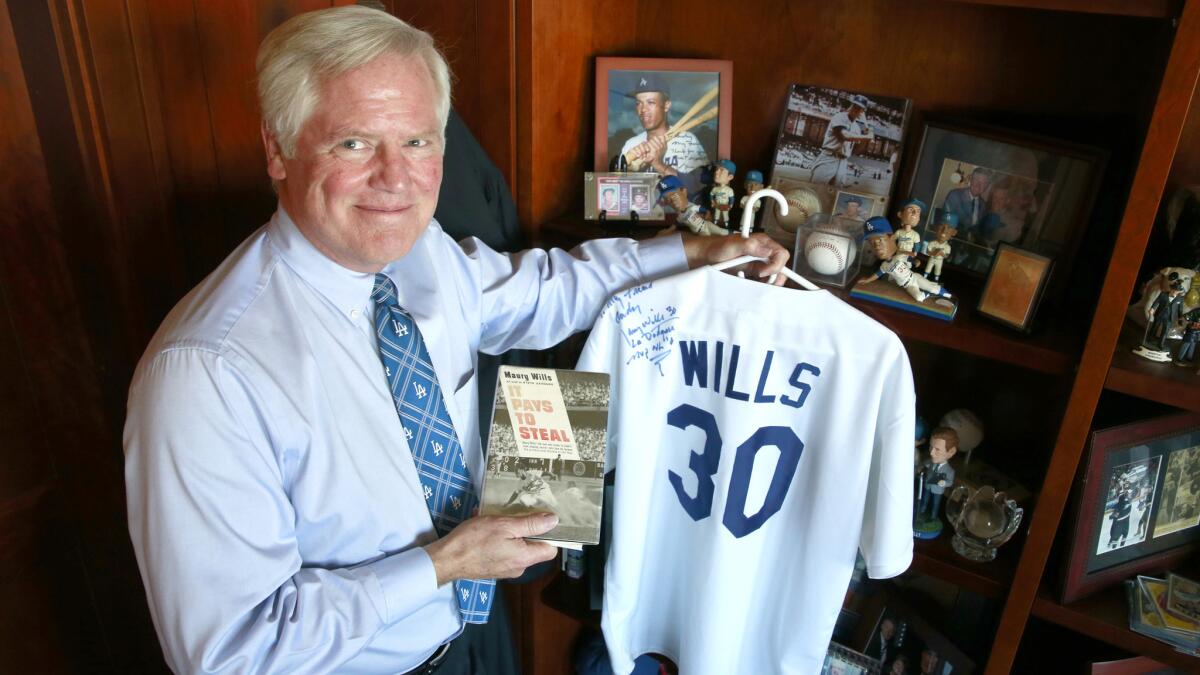

Judge Andrew J. Guilford’s displays some of the Maury Wills memorabilia in his chambers at the Ronald Reagan Federal Building and Courthouse in Santa Ana.

Maury Wills walked into court, accompanying a young man charged with wire fraud. There was a good heart inside that young man, Wills was sure of it.

Wills had gotten into plenty of trouble in his life, beating back the rugged demons of alcohol and drug addiction. He was a seventy-something man who would stand up for someone a half-century younger, offer to mentor him, try to help him get a job and turn his life around.

Would that have any impact on the judge? Who knew? This was a felony charge.

“I was so elated,” Wills said, “when I looked up and saw Andy was presiding over the case.”

That would be the Judge Andrew J. Guilford, appointed to the U.S. district court a decade ago by President George W. Bush. Wills and Guilford had forged an improbable friendship: the street-smart shortstop from the East Coast and the erudite legal scholar from the West Coast.

Their affection for one another came through loud and clear the other day in Guilford’s chambers on the 10th floor of a Santa Ana courthouse, with Wills on speakerphone from his home in Arizona.

Guilford has made it his mission to see Wills inducted into the Hall of Fame. The judge retrieved an overstuffed file on Wills, pulling out a variety of statistics and testimonials making his case for Cooperstown, going line by line over a voting history in which Wills has been rejected for the Hall of Fame 15 times by the Baseball Writers Assn. of America and another five times by veterans’ committees.

He came painfully close the last time, two years ago.

“Three more votes, Maury,” Guilford said.

“Yeah, I know,” Wills replied with a sigh.

“Who’s going to be the next Dodger? It could be Clayton Kershaw, but that’s not going to come for 13-15 years,” Guilford said. “We’ve got to get you elected in the meantime.”

“Andy, you’re more on top of it than I am,” Wills said.

“My job is justice,” Guilford said. “So I hope we get justice.”

Wills will receive the Player Lifetime Achievement Award at the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation gala Saturday in Beverly Hills. The campaign for Cooperstown goes on, the push to induct the seven-time All-Star and 1962 National League most valuable player, the man who revolutionized the art of base stealing in the considerable shadows of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

Guilford has lobbied for Wills for 15 years, from letters to Hall of Fame voters to online petitions to citations in his articles in legal journals (University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 164, Issue 1, page 287, footnote 29: “Famed Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills, whose achievements and intelligence should place him in the Hall of Fame …”).

“He gets upset each year when I get passed up,” Wills said.

Wills said he no longer lets himself get unsettled by the rejections.

“No, not at all,” he said. “I have the joy of knowing and recalling the great career that I had, and where I came from to get there, and what I went through. That’s all priceless. You can’t buy it, as much as I appreciate Andy’s effort …

“Through my program of recovery, I’ve learned to be grateful for where I am, and what I have, and how wonderful my life is. I’ve learned not to hold any ill feelings toward anybody, or any place or thing, for something such as that.”

Wills’ next chance at the Hall comes in 2017. If elected, he would be inducted in 2018, when he would be 85.

“I do believe I will be inducted,” Wills said. “The question is whether they are going to induct me before I die.”

“Ron Santo!” Guilford exclaimed, a reference to the posthumously inducted Chicago Cubs third baseman.

“Ron Santo was an outstanding player, and I think he deserved to be inducted into the Hall of Fame,” Wills said. “But why couldn’t Ron get to enjoy it? If that’s God’s decision, that’s just the way it is.”

Dodger Stadium opened in 1962. Guilford sat with his father in the top deck, at $1.50 per ticket, his binoculars trained on the shortstop. A decade later, when Guilford was in law school at UCLA, he ran into Wills and got his autograph. They chatted again 16 years ago, when Guilford was an attorney, as a judge both men knew was sworn into office. They have been close since, and Guilford proudly displays a collection of Wills memorabilia in his chambers.

Wills said he has been sober for 26 years. Guilford said he has visited with Wills at Dodgers games, often finding him opening his suite to men and women on the road to recovery. When Wills is asked for a suggestion for community service, Guilford is there to provide one.

“Each and every day, I get a phone call from Los Angeles, from some kid who I helped to turn his life around,” Wills said. “We review what he continues to need to do. We review his day, and his thinking. I’ll call him on it, if I think it’s going in a direction it doesn’t need to go.

“There’s about eight of them. I keep my phone close to me at all times. You had a great part in that, Andy.”

Neither Guilford nor Wills remembers the punishment given the young man charged with wire fraud.

“Andy didn’t let him off scot-free,” Wills said, “but he did give him somewhat of a break.”

That was not because Guilford and Wills were friends, but because defendants generally have a better chance at rehabilitation with what the judge called “the support of good people.” That decision came down a decade ago, and Guilford and Wills have kept an eye on that person.

“I think he’s back on track,” Guilford told Wills, “with the support of guys like you and others.”

“Yes, he is,” Wills said. “He’s doing very well. I know what it’s like to have a second chance, even a third chance. People change. All they need is different guidance and inspiration. That’s what happened with me.”

That is a life well lived, regardless of whether a Cooperstown plaque ever comes with it.

Maury Wills at a glance

Teams: Dodgers (1959-66), Pirates (1967-68), Expos (1969), Dodgers (1969-72)

World Series champion: 3 (1959, 1963, 1965)

National League MVP: 1962

Top 10 MVP finishes: 4 (1961, 1962, 1965, 1971)

All-Star appearances: 7 (1961 and 1962 (2 games each year), 1963, 1965, 1966)

Gold Gloves: 2 (1961, 1962)

National League stolen-base leader: 6 (1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965)

First player to steal 100 bases. He stole 104 bases in 1962, most in the major leagues since 1915, when Hall of Famer Ty Cobb stole 96.

Career batting average: .281

Career home runs: 20

Source: baseball-reference.com

Twitter: @BillShaikin

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.