World Series Game 5: An inside look at how a championship slipped away from the Dodgers

Los Angeles Times sportswriters Andy McCullough and Dylan Hernandez and columnist Bill Plaschke look back on Game 5 of the 2017 World Series and discuss how it changed the Dodgers.

The thought flickered through Dave Roberts’ mind when his vision was still clear and his hearing still sharp, before the smoke from in-stadium pyrotechnics clouded the diamond and the blare of the train whistle at Minute Maid Park embedded in his memory.

He stared from the dugout at his fading ace on the mound in the fifth inning of Game 5 of the 2017 World Series. With a three-run lead, two outs and Houston Astros third baseman Alex Bregman at the plate, Roberts pondered his most audacious act as manager of the Dodgers, executed on the sport’s grandest stage: He would take the baseball away from Clayton Kershaw in the middle of an at-bat.

“I’m going to take him out, right now,” Roberts thought as Kershaw snuck a curveball over the plate for a second strike against Bregman. One strike separated the Dodgers from escaping the inning and stepping closer toward the championship that had eluded them since 1988. Roberts believed the best option to collect the strike was warming up in the bullpen, in the person of Kenta Maeda.

Sweat ringed Kershaw’s eyes and dirt dusted his cap. He had chased nights like this for nine years as a Dodger. A lone question lingered over his Hall of Fame career: Could he win a championship? Kershaw had starred in October and he had combusted in October, and he knew the failures resonated and the triumphs evaporated. He had already surrendered a four-run lead, but now he was one strike away from unshouldering a millstone.

All the chaos and anguish that followed, the twists and turns of one of the wildest games in the sport’s history, might have been averted if Kershaw had finished off Bregman. Or if Roberts had intervened.

In the dugout, the manager crossed his arms and studied his pitcher, who was “fighting like heck” to put Bregman away but still fatigued, Roberts recalled. Behind Roberts was pitching coach Rick Honeycutt, who had pitched for 21 years and coached for nearly a dozen more, but Roberts kept his thoughts to himself. He understood responsibility for the decision was his alone.

Bregman stepped out of the batter’s box. Roberts raced through the variables, the value of a fresh reliever versus a weary starter, the potential calamity awaiting when he went to get the ball, the inevitable postgame circus, the concern about embarrassing the greatest pitcher of a generation.

Roberts had spent the past two seasons building trust with Kershaw, to the point where he hoped his ace understood that the manager intervened only when he felt the Dodgers would benefit. But he stayed put. “I didn’t want to make it about me,” Roberts said.

Bregman returned to the box. Kershaw prepared his delivery. The sliding doors closed and the balance of history tilted.

“That at-bat,” Roberts said, “flipped the whole series, essentially.”

Maybe it did.

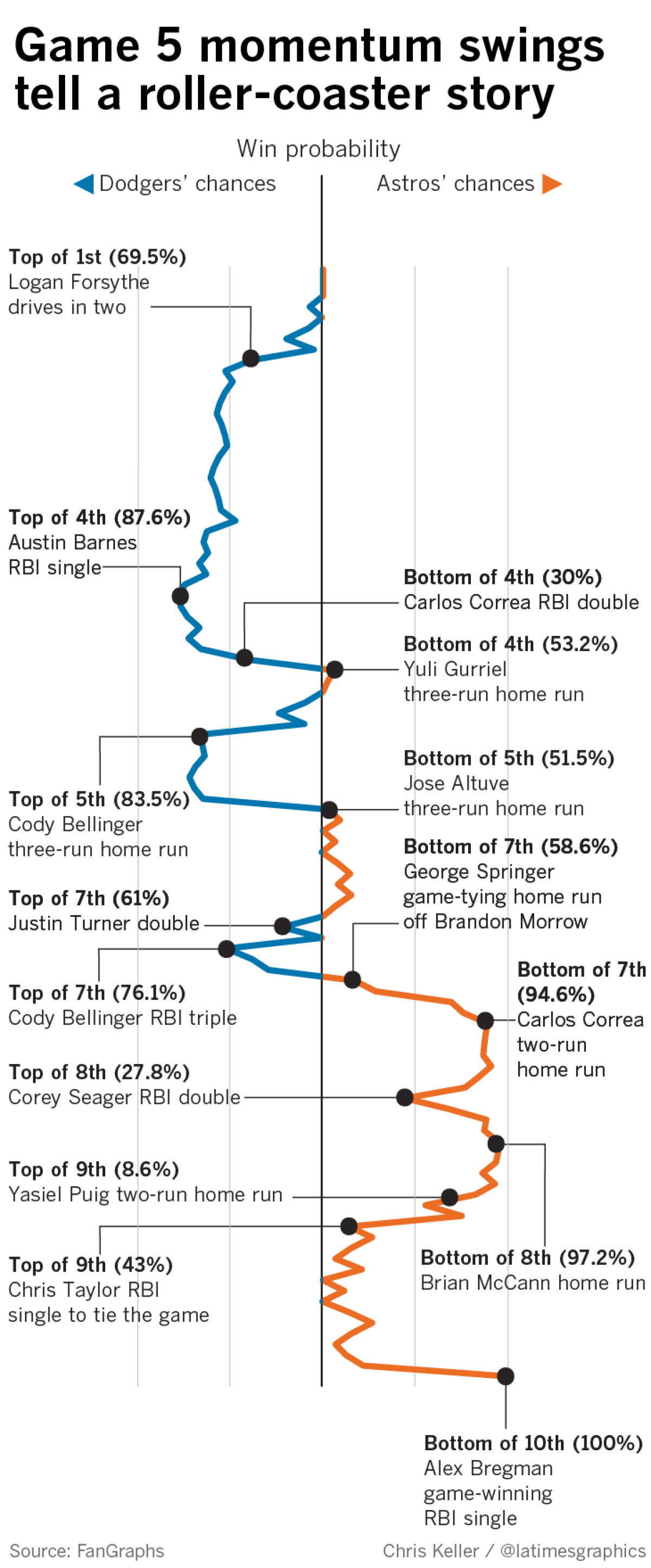

Or maybe the inflection point came in the fourth inning. Or the seventh. Or the ninth. Or the 10th. The moments are not endless, but they feel that way in the aftermath of Game 5, a night of perilous exhaustion, misguided heroism and franchise-altering implications.

“How,” mused Astros outfielder Josh Reddick, “do you pick one thing from that game?”

On Oct. 29, 2017, the Dodgers and the Astros dueled for five hours and 17 minutes. They combined for 98 plate appearances, 417 pitches and 25 runs. Houston scored last to win 13-12.

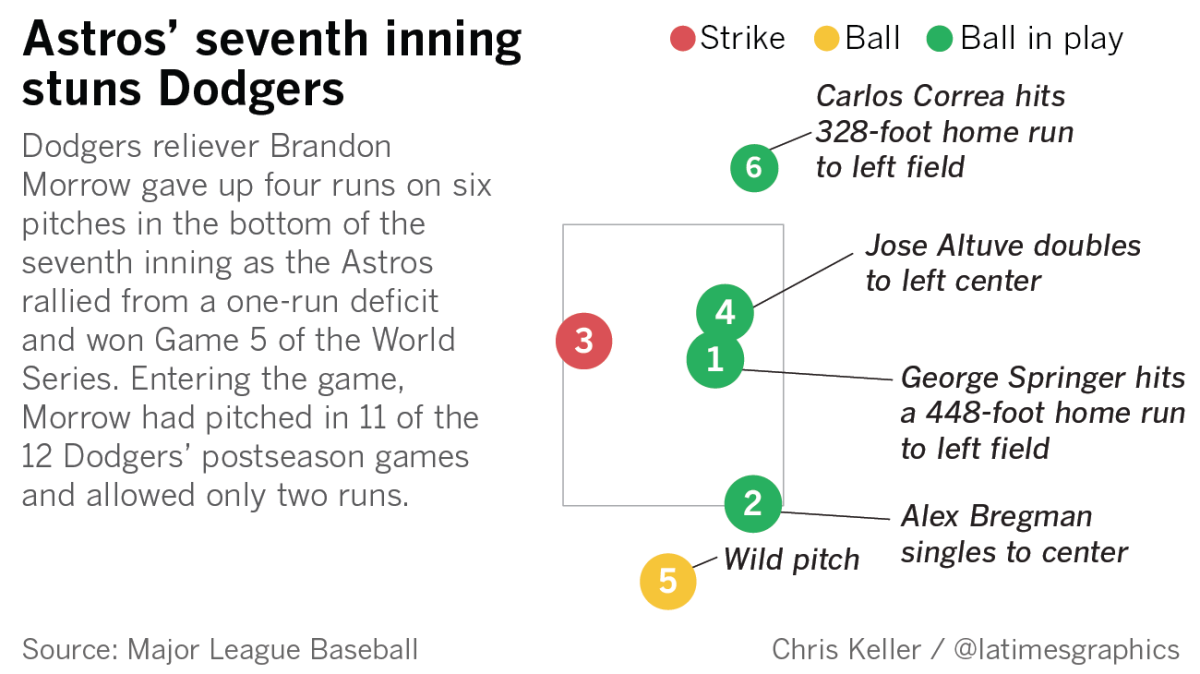

The Dodgers led by four runs and they led by three runs and they led by one run. The Astros erased each in concussive fashion. Kershaw buckled in the fourth and again in the fifth. After Kershaw walked Bregman, Roberts pulled him for Maeda, who served up a tying homer to the next batter, Jose Altuve. Gifted a lead in the seventh, Brandon Morrow suffered a four-run ambush.

“It was the best, worst game in the history of the game.”

— former Astros bench coach Alex Cora

Undaunted by a three-run deficit, the Dodgers rallied to tie the game with two outs and two strikes in the ninth. An inning later, Houston toppled Kenley Jansen for the second time in five games. Bregman delivered a walkoff single to push the Astros one victory closer toward a championship. In the aftermath, the participants alternated between likening the game a roller coaster and a prizefight.

“The thing that wasn’t supposed to happen kept happening,” Dodgers pitcher Brandon McCarthy said. “Over and over and over again.”

The reverberations are being felt in 2018 as the Dodgers prepare for another run at October glory. The loss stained Kershaw’s playoff legacy. It damaged Roberts’ reputation among fans. And it brought the Dodgers to the verge of elimination, which came after a disastrous performance by Yu Darvish in Game 7. Across their three-decade drought, the Dodgers have never been closer to a championship than they were in the moments when victory seemed assured in Game 5.

A year later, the game resonates as an apotheosis for modern baseball, a 317-minute display of the sport’s 21st-century blemishes and its timeless charms. After a season spent pondering the composition of the baseballs, pitchers watched them take flight at an improbable pace. Hitters swung for the fences with abandon. A parade of relief pitchers slowed the game into a slog, mitigated only by the night’s excruciating lows and exhilarating highs.

“It was the best, worst game in the history of the game,” former Astros bench coach Alex Cora said. “It was awful. Bad decisions, bad pitching. But people like runs, man. They do.”

History is written by winners. Over the past three months, The Los Angeles Times spoke with more than two dozen players, coaches, executives and broadcasters to recapture the kaleidoscopic hysteria of that evening. The Astros boasted of photographic recall — “Game 5? I can tell you everything that happened,” World Series MVP George Springer said — while most of the Dodgers professed amnesia. The details faded away. The emotion lingered.

“I will definitely remember Game 5,” former Dodgers executive Alex Anthopoulos said. “I haven’t watched it again. I don’t know if down the road, if it’s on ESPN Classic or MLB Network, I’ll be very curious: Will I change the channel? Will I say, ‘I can’t see this, I can’t watch this’? I don’t know yet.

“Games that mean that much, when you lose, I don’t see how you look back on them fondly.”

Ten days before Game 5, the Dodgers sprayed gallons of Beau Joie and Budweiser inside a cramped batting cage at Wrigley Field to commemorate their first National League pennant in 30 years. The team overcame a hideous September to win more games than they had since the franchise moved to Los Angeles. They were four victories away from a title. Kershaw beamed as he blinked the champagne from his eyes.

“When you’re a little kid, you want to go play in the World Series,” he said. “That’s all you ever dream about.”

The team returned to Los Angeles, where coaches and executives gathered inside offices at Dodger Stadium to scout the Astros and New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series. For four days, the meetings stretched deep into the night. Houston overcame a 3-2 deficit to create a clash between two 100-win teams with elite pitching and frightening offenses, with Roberts pitted against his close friend, Astros manager A.J. Hinch.

The city of Houston had rallied around the Astros after the devastation of Hurricane Harvey. The roster bore the fruits of the franchise’s lengthy rebuild, with Bregman, Springer and Carlos Correa assembled around pint-sized second baseman Altuve. The quartet terrorized pitchers and flummoxed scouts.

All four right-handed hitters possessed power and patience. All four feasted on high fastballs — the signature offering from Dodgers relievers like Jansen and Morrow. The reports from evaluators were not encouraging. The executives scoured video and proprietary information, unable to discern an easy path through the foursome. “We knew going through it that the strength of our guys didn’t line up really well,” president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman said.

To prepare for the first two rounds, Morrow studied pitchers with arsenals like his who had success against his opponents. “We couldn’t really find those guys against the Astros,” Morrow said.

Undergirding the Dodgers’ route to the World Series was their bullpen. They trusted Tony Watson and Tony Cingrani against left-handed hitters, while using Maeda and Morrow against the right-handers. Jansen loomed as a multiple-inning closer. Now they faced opponent capable of trashing that blueprint.

“In the case of the top four in their lineup, it was really a pick-your-poison situation,” general manager Farhan Zaidi said. “You just hope the poison didn’t leave you dead.”

Dallas Keuchel accepted a fresh baseball from umpire Bill Miller and chucked a used one toward his dugout. Silence filled the vacuum around him; the Astros trailed, 4-0, and the fourth inning of Game 5 was still going.

Each of the first four games was a mini-opera. Kershaw outdueled Keuchel and struck out 11 in Game 1. A day later, Jansen blew a save and Houston demolished the Dodgers bullpen. Darvish combusted in Game 3 in Houston. Alex Wood rescued the Dodgers in Game 4 before the offense awoke in the ninth.

Game 5 was a rematch from the opener. As Kershaw cruised early, his teammates produced three runs in the first inning. They were now on the verge of dispatching Keuchel, the 2015 AL Cy Young Award winner.

Keuchel conferred with catcher Brian McCann while massaging the new baseball. The composition of the balls had bothered pitchers all year. The complaints ranged from size to slickness to volatility. The Dodgers collected some as evidence during the season. Sometimes during games, Wood tossed particularly egregious balls to Kershaw, Rich Hill and McCarthy “so they could look and see how ridiculous they are,” Wood said.

Their theories coincided with a historic regular season. The combination of increased velocity from pitchers and amplified aggression from hitters had explosive results. In 2017 hitters bashed 6,105 home runs, eclipsing the record of 5,693 set during the steroidal bloat of 2000. The sport also set a record for strikeouts, turning games into cycles of boom and bust.

Assigning responsibility for the power surge was difficult. Hitters obsessed over the launch angle of their swings, aiming upward and outward, hunting homers above all else. As outings for starting pitchers shortened, games were flooded with inexperienced, mistake-prone relievers. Climatologists wondered if hotter temperatures caused the spike.

And there was this: “Somebody did something with the baseballs,” Hill said.

If the ball was slippery, command suffered. If the ball was wound tighter, it would fly farther. Homers, some pitchers thought, meant bigger ratings and bigger revenues.

“MLB wanted more runs,” Keuchel said. “They wanted more fans. And they got what they wanted.”

Hours before Game 5, Astros ace Justin Verlander spoke for his profession: “Everybody is saying ‘Whoa, something is off here.’” In his lone appearance in the Series, McCarthy tried to spin a slider. The ball did not cooperate, and Springer clubbed a decisive homer in Game 2.

“It felt like one of the better sliders I had thrown in a long time,” McCarthy said. “It came off perfect. And then it just didn’t do what it was supposed to. I turned around, like, ‘That’s a run-scoring double.’ And all of sudden, it was in the stands. I was like ‘Well, this was different.’”

“It didn’t seem like we were down four runs. It almost felt like we were ahead, for some reason.”

— Houston pitcher Dallas Keuchel

Four days later, Keuchel found himself unable to defuse the Dodgers. He would not blame the baseball. Neither would Kershaw, nor Morrow, nor Jansen, nor any of the pitchers who endured Game 5. But the lingering questions were a backdrop for the offensive explosion.

An infield single by Dodgers infielder Charlie Culberson compelled Hinch to open his bullpen. The ballpark hummed at a low ebb, but Keuchel experienced a “weird feeling” as he walked off the mound. He was certain his teammates would electrify the crowd soon.

“It didn’t seem like we were down four runs,” Keuchel said. “It almost felt like we were ahead, for some reason.”

As Kershaw returned for the bottom of the fourth, Hinch confronted a dilemma. He could not concede the game but did not want to expend his best relievers. Cora was heartened by remembering Verlander would start in Los Angeles if Houston faced elimination in Game 6.

On 101 occasions in Kershaw’s career, his offense had provided four runs or more of support. The Dodgers were 100-1 in those games. Hinch understood the odds.

“What you need against elite pitching on the biggest stage is a crack in the armor,” Hinch said. “An opening. A chance to do something. He needs to help you out.”

They perked up at an unexpected gift: Kershaw missed outside with a pair of sliders to Springer, and walked him on five pitches. He fell behind to Bregman before inducing a flyout. Altuve went ahead in the count before smacking a single. “All of a sudden,” Cora said, “he nibbled.”

To the plate came Correa, the No. 1 overall pick in 2012. Kershaw pumped a 93-mph fastball on Correa’s hands. Correa pulled it into left for a double. The Astros had a run. Now they sought more.

After Kershaw bullied the Astros in Game 1, Houston’s hitters regrouped. Their meetings with hitting coach Dave Hudgens usually centered on one word: damage. The Astros led the sport in batting average, on-base percentage and slugging percentage. They were ferocious, but Kershaw had tamed them by tempting them to chase outside the zone.

For Game 5, the Astros condensed their approach. They sought to make contact and stress Kershaw on the bases. They intended to create havoc, Hinch explained, hoping their combination of power, speed and home-field advantage could conquer Kershaw.

Minute Maid Park resembled no other ballpark when it opened in 2000. An adjustable roof amplified the crowd. When an Astro homered, a train rolled along tracks above the diamond. A section of left-field seats called the Crawford Boxes sat only 315 feet from the plate.

“It was harder pitching in their stadium,” Jansen said. “You hit a pop fly, and it’s out.”

The Astros knew Kershaw attacked with a combination of purpose and brute force. He pounded right-handed hitters with inside fastballs before finishing them off with low sliders. His curveball was a spectacle, a 12-to-6 bender that could mesmerize opponents.

When the Astros schemed before the Series, a former Dodger spoke up. Reddick suggested they ignore Kershaw’s curveball and look for the slider, his preferred weapon. “I told them to really see that slider, cutter up,” Reddick said.

With two runners aboard in the fourth, Yuli Gurriel represented the tying run. Inside the dugout, Springer’s chest heaved. Kershaw took the sign from catcher Austin Barnes. Gurriel waggled his bat and waited. A slider spun over the plate. Gurriel vaporized it: 4-4.

“That was probably the craziest game in the World Series, maybe ever?”

— Dodgers' first baseman Cody Bellinger

The three-run homer collided with a sign above left field. As fireworks rocketed toward the roof, the whistle of the train howled. Kershaw stared into left. In the on-deck circle, Reddick raised his arms. Springer did the same in the dugout.

“I’d like to challenge anybody to get in that box against Clayton Kershaw and do what our team had to do,” Springer said. “It’s not easy.”

Kershaw managed to avoid further damage in the fourth, then heaved himself onto the bench and affixed a towel to his left arm. But the ballpark tittered with giddiness as the next inning began. The Astros had landed a hellacious counterpunch. Who could predict what followed?

“That was probably the craziest game in the World Series, maybe ever?” Cody Bellinger said.

Bellinger blasted his way into the picture in the fifth inning. He had slumbered through the first three games, and would finish the Series with 17 strikeouts and a .143 average. Yet he still struck fear with his power.

After walks by Corey Seager and Justin Turner, Astros pitcher Collin McHugh left a curveball over the middle. Bellinger launched it. The three-run shot landed in the first row beyond right-center field and muted the stadium. Bellinger held his finger to his lips after he crossed the plate to put the Dodgers ahead 7-4.

“I was like ‘That’s the game right there,’” McHugh said. “And probably the Series.”

The homer rejuvenated the Dodgers’ dugout. Roberts sought to assemble the bridge from Kershaw to Jansen to secure 15 outs. He did not want to use Morrow after pitching him four games in row. Maeda logged 42 pitches after Darvish’s debacle two days earlier. Roberts needed his starter to keep going.

The Astros hounded Kershaw in the fourth, but his pitch count sat at 67. He was working on regular rest, a rarity in his postseason career. With the bottom of the order due up, Roberts hoped Kershaw could last at least one more inning.

Kershaw retired the first two hitters before his command faded once more. Kershaw screamed at himself after missing away with a 1-0 slider to Springer. The anger did not help. Springer fouled off two full-count fastballs before Kershaw walked him with a low slider.

“I don’t want to say he didn’t have it,” Cora said. “But he didn’t.”

As Bregman approached the plate, Honeycutt trotted to the mound. The delay gave Maeda time to warm up. The umpire handed Kershaw a strike on a first-pitch curveball. The count drew even on an outside fastball. Then Kershaw snapped off the curve that triggered Roberts’ impulse to go with Maeda for the last strike.

“Based on what I know about Dave, and what I know about the Dodgers, it wouldn’t have surprised me,” Hinch said. “It would have been a bold move, given it’s Clayton Kershaw and all that comes with it.”

Roberts opted for convention. Bregman fouled off a trio of 93-mph fastballs and spoiled a two-strike curve. On his 94th pitch of the game, and the 10th pitch of the at-bat, Kershaw lost Bregman on a slider in the dirt. Roberts was on his way to the mound moments later. The ace said nothing as he handed the ball to his manager.

The Dodgers led by three as Maeda entered the fray. Awaiting him was the American League MVP. Altuve owned three batting titles. He set a career-high for slugging in 2017. His 5-foot-6 frame compacted his strike zone and his hands flashed like lightning. “Altuve,” Hudgens said with a grin, “hits everything.”

Maeda learned as much. Altuve hooked a 3-2 slider down the left-field line, feet shy of a tying homer. The crowd serenaded Altuve with “M-V-P” chants. Kershaw sat on the bench and wiped his palms across his thighs. His teammates huddled on the railing. The next pitch shattered them.

Barnes asked for a fastball, down and away. He lifted his glove as the pitch veered inside. It never reached him. Altuve demolished it to dead center. Springer stomped on the plate and pirouetted: 7-7.

The television broadcast fixated on Kershaw. A camera caught his reaction. He flinched when Altuve made contact. Kershaw rose to follow the ball’s flight. Then he returned to his seat, alone on the bench.

“I’ll forever feel bad for him in that situation,” McCarthy said. “Not just for the team, but for him. Because it’s Kersh. As good as he is, as hard as he works, you want that to be his moment, his time.”

One afternoon last month, Kershaw was loosening up before batting practice when a reporter brought up Game 5. Kershaw locked his eyes on his lumber as he spoke. He lacked interest in the topic.

“I don’t really reflect on it that much,” Kershaw said.

Kershaw lives within five-day cycles, purging successes and failures after each start. He holds himself to a standard to which even Hall of Famers cannot relate. “This may sound like a defense of him, but I never had 34, 35 playoff games in the regular season,” said John Smoltz, a member of Cooperstown’s class of 2015 who is an analyst for Fox.

Smoltz was in the booth for Game 5, and he empathized with the man on the mound. In the postseason, Smoltz theorized, every player tries to raise his game. Yet Kershaw maximized his ceiling every fifth day. There was no way to raise the bar, Smoltz said.

“When you’re putting up Cy Young, stupid numbers like he does every year, the level of expectation is so great for him that it’s literally like him pitching a postseason game every single game,” Smoltz said. “And then all of a sudden, he’s supposed to be better? It’s impossible.”

Kershaw offered no response when informed Roberts considered removing him midway through the at-bat against Bregman. If Game 5 torments him, he would not say how much.

“Not a great experience,” Kershaw said. “There’s no other way to put it.” He paused for five seconds. “I mean, yeah. That’s really it. Not fun.”

When the ball left his bat, sizzling into center field at 100 mph, Bellinger assumed he had made the second out of the seventh inning. The liner was headed for Springer. Fearful of Bellinger’s power, Springer was positioned near the wall. As he barreled forward, extending his left hand to make the catch, the baseball dived toward his right side, the result of topspin.

Springer tumbled into the grass. The baseball skipped by and rolled to the wall. Hustling from first base, Enrique Hernandez scored to put the Dodgers back ahead 8-7. Bellinger halted at a stop sign from third base coach Chris Woodward.

Woodward patted Bellinger on the back. In the outfield, Springer hunched at the waist. He stared at the ground and shook his head.

“If we lose the World Series, it’s because of this play.”

— Houston outfielder George Springer

“If we lose the World Series,” Springer thought, “it’s because of this play.”

As Springer smoldered, Ross Stripling warmed up in the Dodgers’ bullpen. The four-headed monster of Houston’s lineup was due up in the bottom of the inning. Stripling was in between tosses when he saw Morrow leave his seat, remove his hoodie and grab his glove. Morrow found bullpen coach Josh Bard.

“Call down,” Morrow said. “Tell them I want it.”

Morrow was an unlikely workhorse. Injuries handcuffed him after the Seattle Mariners chose him with the fifth pick in the 2006 draft, two slots before the Dodgers took Kershaw. In January 2017, he reinvented himself as a reliever on a minor league deal with the Dodgers.

After Morrow debuted in June, the team treated him with care, avoiding using him on three consecutive days. He earned Roberts’ trust with the conviction of his approach and the blaze of his fastball. He became Jansen’s setup man, a vital cog in their NL-best bullpen and a crutch in the team’s late-game planning.

The usage pushed Morrow into uncharted waters. He had already pitched in 11 of 12 postseason games, yet he still demanded the baseball. “That’s why I loved Brandon so much,” Roberts said.

Roberts knew that Morrow was fatigued, but he could not forget how his other right-handed relievers fared in Game 2. The Astros pounded McCarthy and Josh Fields. Stripling betrayed his nerves with a four-pitch walk. Morrow was not fresh, but he was willing.

“If this guy wants the baseball, I can’t deny him,” Roberts said. “It’s what it’s all about. It’s the World Series. I try to take it out of the players’ hands. But then when he steps up, you have to give him the baseball.”

Roberts added, “You have to look and say ‘Who is a better option?’”

As the coaches deliberated, Stripling waited for a verdict. When Morrow stepped to the other mound, Stripling went back to his seat. “Nobody in a million years thought that was a selfish decision, or anything,” Stripling said. “At the time, we thought it was like a boss decision. We were like ‘Oh, hell yeah.’”

Morrow trotted to the diamond in the midst of the seventh-inning stretch. As the fans sang “Deep In The Heart of Texas,” Morrow swiped a handful of dirt off the mound and rubbed his fingers together. His arrival perplexed at least one Astro.

“The same guy?” Gurriel asked.

“Yeah,” Cora said. “The same guy.”

The tension seeped into a suite hosting members of the Dodgers’ front office. The stress was “orders of magnitude more intense than I thought possible,” Friedman said. Amid the suspense, there was no disagreement with the deployment of Morrow. “He was the right guy in that spot,” Zaidi said. “Sometimes it just doesn’t work out.”

Due up first was Springer. His coaches had tried to cheer him up when he returned to the dugout. “Let’s win every pitch,” Cora told him. “Turn the page.” Hinch had a similar message — “Keep playing,” the manager said — but he was unsure it landed. Springer grabbed his gear and hustled into the on-deck circle, hellbent on reaching first base.

“If I have to headbutt this ball, I’m going to do it,” Springer told himself.

Morrow tested him with a first-pitch fastball. The pitch hummed at 95 mph, a few ticks below the 97.7 mph Morrow averaged. It caught too much of the plate and too much of Springer’s barrel. The baseball disappeared over the train tracks to tie it at 8-8.

Springer hollered as he rounded first base. There was bedlam in the ballpark. Fireworks exploded and the train whistle blared. As Morrow circled the mound, the Astros mobbed Springer. After he shook a cup of sunflower seeds from his hair, Springer looked wide-eyed and dazed. He escaped the dugout, sat on the ground of the tunnel and held his head in his hands to steady himself.

“It’s a feeling I’ll never be able to explain to anybody,” he said.

By the time Springer rejoined his teammates, Morrow was caught in a storm. His outing lasted six pitches.

Pitch No. 2: A slider over the middle. Bregman cracked a single.

“We saw Morrow every game,” Bregman said. “We saw a lot of him. It makes a difference when you know what their stuff looks like.”

Pitch No. 3: A slider for a strike to Altuve.

Pitch No. 4: Back to the fastball, 97 mph. Altuve clubbed a go-ahead RBI double.

“This is un … believable,” Hinch told Cora.

Pitch No. 5: A slider to Correa bounced for a wild pitch. Altuve scooted to third. In the bullpen, Cingrani got loose.

Pitch No. 6: A 96-mph fastball. The pitch zoomed above the strike zone, but Correa still swung, looking for a fly ball to bring home the runner. Morrow turned to watch. Joc Pederson sprinted along the warning track as the baseball hung in the air. It descended three rows deep in the Crawford Boxes, a mere 328 feet from the plate, to give the Astros an 11-8 lead.

The cycle of noise repeated: Fireworks. The train. The tumult punctured the cocoon of the Dodgers’ suite. “Nothing in baseball makes your stomach churn like the sound of the opposing team’s playoff crowd,” Zaidi said. “Those were a very loud six pitches.”

Roberts looked disgusted when Correa’s homer fell. The infielders surrounded Morrow. After the game, teammates, coaches and executives would commend his attempt at valor. The words did not quell his remorse.

“I regret that I put myself in front of some guys who had done a lot of good things for us that year,” Morrow said. “And were obviously much fresher. There’s obviously second guesses when you go out there and give up four runs in six pitches.”

Springer stood in front of his locker in August when the Astros visited Dodger Stadium. He recalled how thin the margins were during the wildest game of his career.

“I don’t think a lot of people understand how close it was to going the other way,” Springer said. “For them having that championship. For them outslugging us. For them outpitching us.”

After Morrow capsized, the teams traded runs in the eighth. Seager smashed a one-out RBI double, with Chris Taylor holding at third base. Turner and Andre Ethier could not bring him home. Houston answered with a homer from McCann off Cingrani.

When the ninth inning began, Houston led 12-9. The advantage shrank to one when Yasiel Puig lined a two-run shot into the Crawford Boxes. Barnes followed with a double. Taylor poked a two-out single up the middle to tie the score at 12-12.

“Great job, Austin!” Roberts shouted at Barnes. By this point, Bellinger recalled, his feet ached and his voice was hoarse. He was not alone. Hope flickered.

“There’s no way,” Hernandez thought, “we can lose this game now.”

Yet they did.

As Hinch repeated “We’ve got to stay tied” to Cora, Seager lined out to strand Taylor in the ninth. After felling Kershaw and blitzing the relievers, the Astros chopped down Jansen, the last line of Dodgers defense.

Jansen collected three outs in the bottom of the ninth and retired the first two Astros in the 10th. He then lost the handle on a 2-2 cutter and hit McCann. Unable to command the baseball against Springer, Jansen issued a five-pitch walk. Hinch sent outfielder Derek Fisher to run for McCann at second base and stopped to speak with Bregman.

Hinch recalled a lesson from Charlie Manuel, a hitting guru who managed 12 years in the majors. Manuel preached the importance of a compact swing with runners in scoring position, the sort of lesson lost on the modern hitter. Now Hinch repeated it.

“Beat him with a single,” he told Bregman.

The manager found a pupil willing to listen, a player who “digests information and applies it,” Cora said. Bregman brimmed with confidence and talent. He was chosen with the second pick of the 2015 draft, but carried himself with the determination of a late-round selection. He wore No. 2 because he was irritated he wasn’t taken first overall. His size played a role in his demeanor — the Astros listed him at 6-0, but that appeared a multiple-inch exaggeration.

“He has that giant-killer mentality,” McHugh said. “If anybody was going to do it against Kenley, it was going to be him.”

Bregman faced Jansen for the first time five days earlier. He lined out to center field for the penultimate out of Game 1. The at-bat only amplified his swagger. “He has nothing,” Bregman told Cora. “I got him.”

A day later, Roberts sent Morrow to face Bregman in the eighth inning of Game 2, rather than have Jansen start the inning. Roberts hoped a different look might fool Bregman. Instead Bregman hit a ground-rule double off Morrow, Jansen gave up an RBI single to Correa and the Astros were trailing by only a run when Marwin Gonzalez pulverized an 0-2 cutter from Jansen in the ninth.

Now Roberts had little room to maneuver. He needed Jansen to get through the 10th, and he hoped someone else could handle the 11th. On the mound, Jansen dabbed at sweat above his eyebrow and adjusted his cap. He had thrown 89 pitches in four appearances over six days. He secured Game 1, granted Houston life by blowing Game 2 and finished Game 4 to tie the Series, although he did give up a home run to Bregman.

Bregman knew a cutter was coming. The pitch broke across the plate and Bregman lined it into left field for a single. The throw by Ethier had no chance. The Dodgers had led by four and then by three and then by one — and still they lost 13-12.

Jansen shuffled off the mound as the Astros danced around the diamond. Roberts waited by the corner of the dugout to salute each member of his team as they exited. Above, fireworks burst and the train blared.

“I gave everything I had,” Jansen said. “I’m not feeling guilty or anything. You just have to tip your cap to the Houston Astros. They deserved it. They were the better team.”

A nightmare recurred for Farhan Zaidi this winter. He did not hear the roar of the train whistle or watch rockets soar toward the roof of Minute Maid Park. He felt a more primal ache.

“I had dreams where we were in the midst of that series, and it wasn’t over yet,” Zaidi said. “There was still a feeling of hope, that you might actually win the World Series. And then you wake up, and you're like ‘Oh, yeah, we lost.’

“Is it worse to have a nightmare and then wake up from it? Or is it worse to have a dream where you still have some hope, and then you realize the hope is gone?”

The defeat in the World Series jostled the continuity of the franchise. The team stumbled through the 2018 regular season before winning a tiebreaker to claim the National League West title. Kershaw can opt out of his contract after this season. Roberts managed as a lame duck, while Hinch received an extension from Houston.

One day this winter, Hinch hunkered down with his wife to rewatch Game 5 in its entirety. He marveled at what he remembered and all the details he missed. “I’ll always remember it as the best game I’ve ever been a part of,” Hinch said. “Easy to say, because we won.”

Roberts said he never considered browsing the highlights. The two toured museums together with their families in Washington during All-Star festivities this summer. Neither man brought up the World Series. Hinch was wary of inflaming his friend. For Roberts, the memories were still too sharp.

Maybe after they retire, Roberts said, they could sit and watch those games again, revealing some of their strategy, asking questions they had stowed away. They might even watch Game 5.

“It was one of the best World Series in major league history. Period,” Roberts said. “Someone had to win. Someone had to lose.

“Do I hate that we didn’t win?

“Absolutely.”

Twitter: @McCulloughTimes

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.