Column: There’s too much talk about baseball games being too long

The games take too long. How can the sport grow its fan base when the games take so darn long?

Three hours for a regular-season game, longer in the playoffs, almost four hours in the game that crowns the season champion.

Rob Manfred had better do something.

The first thing the commissioner ought to do is to tell the conventional wisdom to take a timeout. Those are the average game times for the NFL.

“The Super Bowl,” Dodgers closer Kenley Jansen said, “is four and a half hours.”

Jansen is embellishing, but not by much, and he is doing so in the service of the story line that Major League Baseball ought to embrace. Talk up the sport, talk up the players, and stop talking about how long it takes to play a game.

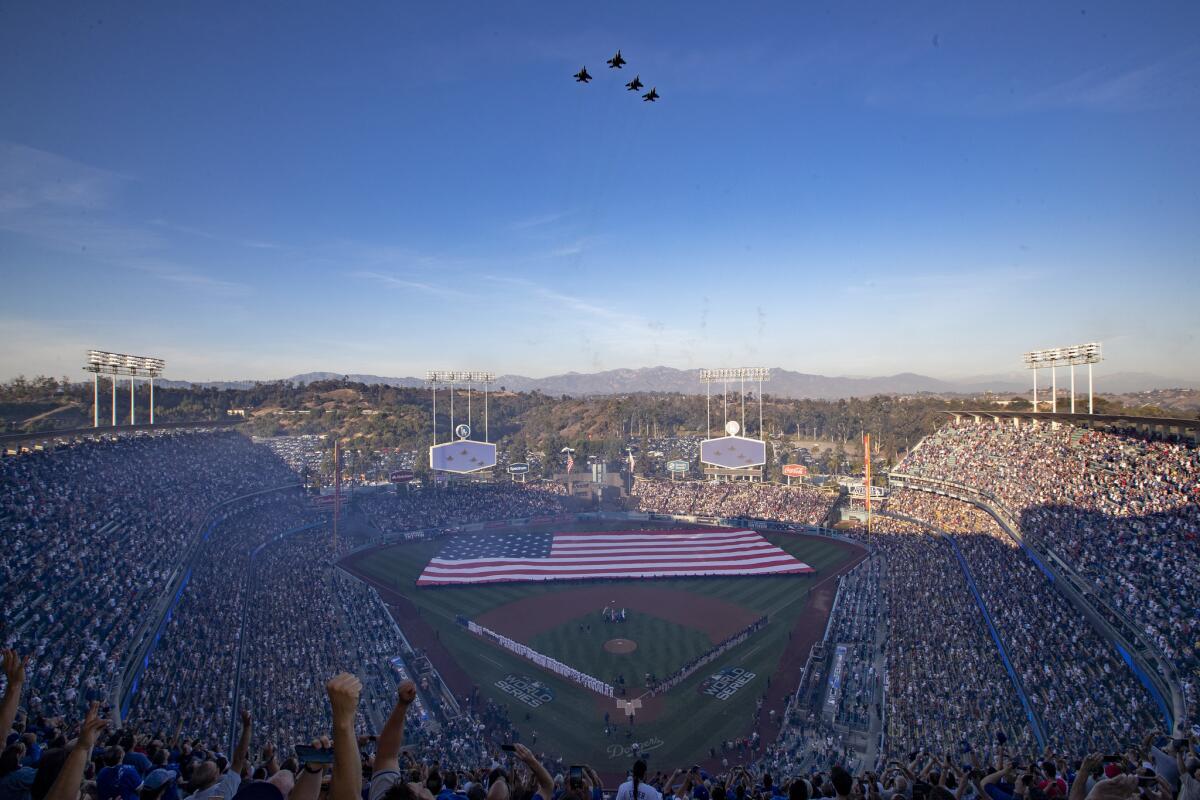

On the day before this year’s World Series started, with the Dodgers playing for their first title since 1988 and the Boston Red Sox playing for their first title since 2013, Boston second baseman Dustin Pedroia scoffed at the notion that his team’s fans might be offended, or even concerned, at how long the games take to complete.

“No one remembers game times of the 2013 World Series,” Pedroia said. “Nobody cares. But they know who won.”

Justin Turner, the Dodgers’ third baseman, loves to tell the story of how he was watching from his grandmother’s house when Kirk Gibson hit his legendary 1988 home run. That is the kind of story the league should be selling.

The Gibson game took three hours and four minutes. The average postseason game took three hours and 29 minutes last year, three hours and 35 minutes this year (excluding extra-inning games, since an 18-inning game that goes almost 7 ½ hours skews the numbers).

Turner said the additional half-hour — some because analytical theories have led to more strikeouts, walks and pitching changes, some because of extra time for television commercials — should not cause fans to lose interest.

“The games are long, but I think they’re action-packed,” Turner said. “They’re full of entertainment. If you look at last year’s World Series — and not just because I played in it, but as a fan looking from the outside in — it was probably one of the best World Series that I’ve ever seen. The action, the back and forth, the excitement, having the fans hanging on the edge of their seat. I don’t think they’re going anywhere.”

But the late nights, and the children … won’t someone please think of the children?

“They can hang with it,” Boston outfielder Jackie Bradley Jr. said. “I believe in the kids.”

The cries of “the kids can’t stay up late” are repetitive and outdated. You might have had to gather around the family television set to watch Gibson’s home run 30 years ago, but today you can watch on your phone. A quarter of a million people did exactly that when the Red Sox clinched Sunday — a relatively small but fast-growing segment of the audience.

The kids might even sneak a phone under their covers at bedtime, just as the kids of the Gibson generation could do with a transistor radio. The final score and the highlights are available on demand now, so kids can click and check when they wake up in the morning.

Baseball is the fastest-growing major team sport in the United States, and more kids under 12 play baseball (or softball) than any other sport, according to the Sports and Fitness Industry Assn.

“You can’t ignore the fact that it keeps growing,” Dodgers second baseman Brian Dozier said. “It’s not like it’s a steady dip.”

In reality and in image, Manfred’s dogged pursuit of a 20-second pitch clock has backfired. It leaves the false impression that knocking three minutes off the game time will solve the riddle of slow play, and it antagonizes the players who resent the “agree to this, or else” push from the owners.

“If you just step on the mound and fire it in there, and you give up a home run to a fastball hitter, you probably should have thought about something else,” Pedroia said. “If that takes time, it takes time. We’re trying to win.”

Dozier said the players this winter plan to present their own proposals for speeding up games. He wouldn’t say what they were, but he understood the need for them.

“I think the culture we live in is very quick-paced,” he said. “We’ve got to have things now, in everything. Baseball might be a little drawn out. I think that’s what makes baseball rather unique. It’s without a clock.

“Some things we could keep cleaning up. We’ve done a good job of that the past few years, and we’ll continue to do that, just to speed it up a little.”

The players also would appreciate it if the league would listen closely to their ideas on how to market the game, and its greatest stars. In return, the players should appreciate that the game is an entertainment product, and that a lethargic product can tempt consumers to change the channel, or pick up a video game, or go take a hike.

Manfred is right to be concerned about alienating the audience, particularly younger fans raised on neighborhood Little League games, which take six innings and do not include two minutes between innings for television commercials. He is right to be frustrated that attempts to pack more action into a game get shouted down in the name of tradition.

The three-point shot did not kill the NBA. The Golden State Warriors are a joy to watch, precisely because the three-point rule breathed new life into the league.

The world’s most popular sport, soccer, limits substitutions to three per game. That, really, is where baseball should consider reform: some sort of limit on substitutions. Too many matchup decisions are more of a bane than too many seconds between pitches.

The NFL has uniquely positioned itself for popularity. Your team plays once a week, usually on Sunday. There is plenty of dead time in football, just as there is in baseball, but dead time in football can be devoted to checking on the players on your fantasy league team.

Why is three hours too long for an MLB game, but not too long for an NFL game? In part, it is because the NFL does not talk about how long its games are. Manfred should stop talking so much about that.

And, above all, stop talking about television ratings. No one would ever say, “Gee, I would have watched the World Series, but the ratings were bad, so I didn’t.” Grow the game, and the ratings might follow — or they might not, since determining popularity based on how many people watch the game on their living room television might not be an optimal measurement for the streaming generation.

Borrow a page from the managers, and the general managers. Any question about ratings should be met with this response: “We’re just here to talk about baseball.”

When the popular narrative leans more to “baseball is dying” than “football players are dying,” the message ought to go beyond a pitch clock.

Follow Bill Shaikin on Twitter @BillShaikin

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.