Doc Rivers on Kobe Bryant: ‘Mamba mentality’ changed the NBA

Doc Rivers was at a charity function one year ago in Los Angeles when he looked up to an unexpected sight: the arrival of Kobe and Vanessa Bryant.

Some of Bryant’s most memorable clashes during his 20 years starring for the Lakers had come against Celtics teams coached by Rivers. Back and forth they went in 2008 for six games in the NBA Finals until Boston prevailed, and before Bryant left the court, he stood and talked with Rivers amid the confetti.

“He’s crying and I’m hugging him and we’re talking and I can feel not only his tears, I can feel his revenge anger in that moment,” Rivers said by phone last week. “Every breath of him was thinking, planning, ‘I’m getting you guys back.’”

Bryant did so two years later, in a Game 7 victory over Boston, and would call his fifth championship his favorite. Bryant’s drive made him the “perfect opponent,” Rivers said. Yet for all of their famous meetings, their relationship had rarely gone deeper than quick greetings. That began to change, Rivers said, following Bryant’s 2016 retirement.

Rivers lived near Los Angeles, coaching the Clippers, while Bryant embarked on his post-basketball career from Orange County, and when their paths crossed, they retreated into longer conversations. When they saw each other at the charity event, it was the second time they’d caught up in a month.

“We ended up in some corner talking and again, always about ’08 and ‘10,” Rivers said. “It’s amazing how quickly we were back there. … He would ask questions like, ‘What was your mind-set trapping me in Game 7, you hadn’t trapped me all year — that surprised me.’ I mean, he said, ‘That got me in the first half. Y’all got me with that one.’

“We would laugh about stuff. Him throwing the pass to [Ron] Artest, he said, ‘I knew you guys didn’t think I would make that.’ It was that kind of talk. It was great talk.”

It would be their last.

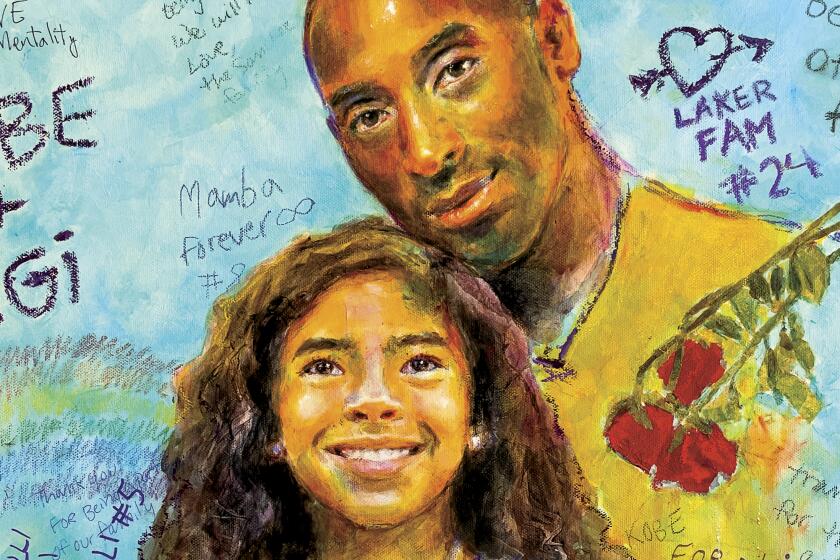

Three weeks later, after Bryant, his daughter Gianna, and seven others were killed in a helicopter crash near Calabasas, Rivers wept in front of reporters in Orlando, Fla., before a game he said neither team was emotionally prepared to play. This week, as the crash’s one-year anniversary nears, Rivers said an element of shock remains and that his wounds, and those of the NBA, remain “very fresh.”

“Getting to know him over that last six months and then all of a sudden that’s gone, was for me, personally, just devastating,” Rivers said.

Rivers had begun Jan. 26 not as a coach but a grandfather, visiting Austin Rivers’ young son just outside Orlando. That emotional high lasted until the early afternoon when, while preparing to leave the Clippers’ hotel for a ride to the arena, he received a call from longtime KCBS-TV sports anchor Jim Hill, who warned Rivers that he believed something tragic had occurred involving Bryant.

As more details became public, Rivers felt grief on different levels. The Sikorsky S-76B helicopter had crashed amid fog and low clouds en route to a youth basketball tournament at Bryant’s Mamba Academy in Thousand Oaks. Also aboard were Gianna Bryant’s teammates, their parents and coaches. Rivers thought about the years he spent as a self-described “AAU dad,” helping ferry his four children and their friends to high-level youth tournaments across the country. He can still hear kids joking in the backseat.

“I remember a million times having half a team in my car,” Rivers said. “That’s just the way it was. Then to see that, you know exactly what he was doing. You know why he was doing it. You put yourself in those exact positions.”

As a player during Michael Jordan’s prime, Rivers watched a generation pattern their playing style on the Bulls great — Bryant included. But until he reached the arena in Orlando, walking into a “devastated locker room that needed counseling, that needed hugs,” Rivers didn’t realize the extent to which Bryant had become the template on which so many in the league had modeled their game.

Southland stars Paul George and Kawhi Leonard, now with the Clippers, grew up watching Bryant before later forming relationships with him as they rose within the NBA. On Bryant’s recommendation, Leonard said he had even hired the same pilot involved in the crash to commute from his home near San Diego to Los Angeles. Guard Lou Williams played for the Lakers during Bryant’s final season. Rookie guard Terance Mann said a book written by Bryant changed his life. Center Ivica Zubac idolized Bryant as a teen playing in Croatia but, even while starting his career with the Lakers, never met him Bryant. When Bryant’s jersey was retired at Staples Center in 2017, Zubac was on assignment with the Lakers’ G League team.

Kobe Bryant, daughter Gianna and seven others perished in a helicopter crash on Jan. 26, 2020. Remembering the Lakers legend a year later.

“I had to watch it on TV,” Zubac said last summer. “That was painful for me.”

Said Rivers: “His long-lasting impact, at least the current one, is how many players try to design their game and their whole being like Kobe, and have the ‘Mamba mentality’ like Kobe,” Rivers said. “He changed the game in that way, and that’s a sign of greatness.”

Rivers has had a year to think about the day; what he comes back to is the emotional detachment felt during his team’s eventual victory against Orlando. Rivers said little during timeouts. Glancing at his coaching staff during the first half, he saw assistant Tyronn Lue, a friend and former teammate of Bryant, crying on the sideline. He tried telling his team to focus during a halftime speech, but it fell flat because he wasn’t able to focus himself.

“I swear for me that whole game, I just could not get my mind off it,” Rivers said. “Just what happened, the tragedy of that, you know how your mind goes there. And then Vanessa … that was crushing for me, being a parent.

“I think it was Kawhi in the middle of the third you could just see him say, ‘I’m not losing this game.’ Other than that, neither team cared. Even one of the refs made just an awful call and I didn’t say anything and he looked over and I was like, ‘What do you want me to do, bro?’ And he actually said, I can’t think of his name, he said, ‘Man, I don’t have anything tonight.’ It affected everybody.”

One day Rivers hopes any mention of Bryant will evoke joy for those who remember his relentless playing style. By Rivers’ own admission, he is not yet there.

During the early weeks of the pandemic last spring, Rivers happened to catch a replay of Game 7 of the 2010 Finals. The broadcast helped him spot some details of the game he’d forgotten. He also saw the moments Bryant had not, the ones he’d asked Rivers about on that January night.

Bryant was “just allowing the outside world in,” Rivers said. That included him, too.

“I haven’t reached that joy yet, where we should embrace it,” Rivers said. “I’m sure we will. We do with everyone. But I haven’t gotten to that point yet.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.