Steve Ballmer’s ‘juiced’ enthusiasm for Clippers is helping transform team

Steve Ballmer was golfing with a longtime colleague and friend late last month when the conversation turned to what had happened a few days earlier.

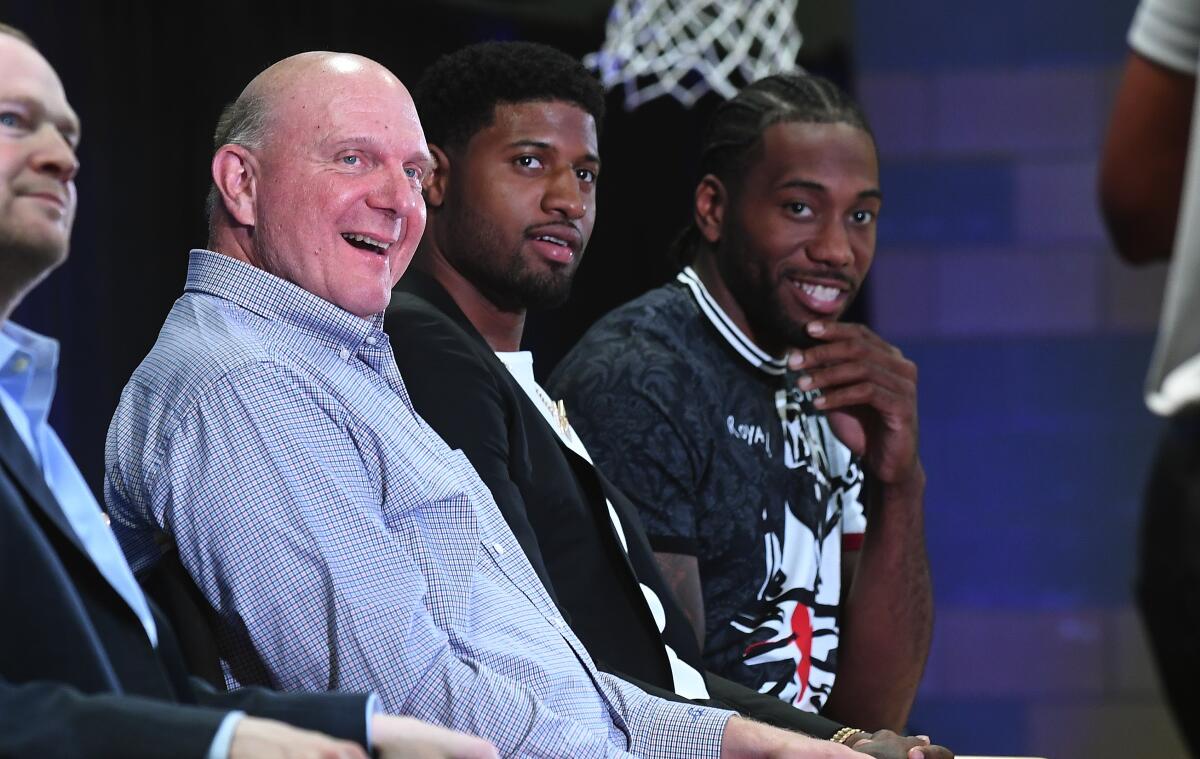

On a stage inside a standing-room-only recreation center in South Los Angeles, the Clippers owner burst out of his director’s chair, grabbed a microphone, and introduced superstar forwards Kawhi Leonard and Paul George with whoops and hollers that quickly went viral across social media.

“It was kind of like our old sales meetings,” Jeff Raikes said Ballmer told him. “I knew what he was referring to.”

Before he left Microsoft in 2008 to become chief executive of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 20 of Raikes’ 27 years at the tech firm were spent working directly for Ballmer. His boss became famous for whipping himself, and employees, into a frenzy at company conferences.

But if Ballmer’s outburst during the Clippers’ announcement was nothing new for Raikes, it was unexpected for plenty of other people.

“I came off the stage,” Raikes recalled Ballmer saying, “and Kawhi said, ‘Man, I gotta get me some of that juice.’”

That ebullience, what Leonard called Ballmer’s “juice,” is genuine, friends and colleagues say.

So is the competitive streak that runs as deep as his pockets.

Ballmer grew accustomed to winning during his 34-year career at Microsoft, helping grow what had been a small company into a giant of the tech industry while amassing a personal fortune north of $50 billion. Current and former colleagues say understanding Ballmer‘s success selling software in Seattle is key to knowing how, five years into his ownership of the Clippers, the team has become one of the big winners of the NBA offseason.

A franchise long derided for mismanagement has become a model for other NBA front offices. And a team dogged by the “Clippers curse” of losing is one of the betting favorites to win the 2020 NBA title.

“Steve wants to win, plain and simple,” said Martin Taylor, Ballmer’s chief of staff at Microsoft from 2002 to 2006. “That hasn’t changed with how he’s approached things with the Clippers.”

Ballmer’s competitiveness formed during a middle-class upbringing in Detroit, where his parents “instilled in him an intensity to be the best he could be,” Raikes said. A star student, Ballmer attended Harvard, where he kept statistics for the men’s basketball team.

In the 1980s, as Microsoft grew, Ballmer became friendly with coaches of the “Bad Boy” era Pistons during his hometown team’s visits to Seattle. Occasionally, he sat just feet from the bench.

He played too, during morning pickup games with fellow executives at a suburban health club. “He sets good screens,” Taylor recalled. “He can hit an open shot.”

As Microsoft’s CEO from 2000 to 2014, Ballmer treated as royalty the software engineers who wrote the backbone of the company’s products. Their offices had a special layout to promote efficiency. Unlike others whose upward mobility within the company required leading teams of employees, the best programmers could rise to the equivalent of a vice president just by being excellent at their job, Raikes said.

Ballmer played to his strengths as a salesman and numbers wizard, and where he lacked technical expertise, such as in software engineering, he installed trusted teams and gave them freedom to work with little meddling.

Raikes, who ran Microsoft’s worldwide business operations, said Ballmer’s strongest suit was his ability to recognize patterns amid huge amounts of data. He recalled a grueling week in 2000 with Ballmer spent evaluating the performance of dozens of the company’s European subsidiaries. During one evaluation, well after midnight, Ballmer’s mental numbers-crunching and piercing questions revealed that he understood the books of a Polish subsidiary better than the company’s own leadership.

During an interview with The Times in February, Ballmer described his style of management as, “stay involved, ask a lot of questions. Generally people will have good answers, and you let them do what they’re going to do. And if they don’t have good answers, then you’ve got to push harder.”

As Ballmer’s wealth grew, so did his interest in NBA ownership. Over several years, he kicked the tires on the Milwaukee Bucks and Seattle SuperSonics and was involved with a prospective ownership group that eyed the Sacramento Kings. In 2014, Ballmer paid an NBA-record $2 billion to purchase the Clippers from Donald Sterling, who had been banned for life by the league after being accused of making racist statements.

Ballmer immediately confronted a steep learning curve. “I’m not sure I knew what I was getting into, good, bad and ugly, when I bought it,” Ballmer said. “I’ve probably never even lived in a place where there was a franchise that had been run any worse than the Clippers had been run. Or certainly where the ownership was less respected.”

To start, Ballmer didn’t fully grasp how the league’s 30 franchises shared revenue. Ditto for its tax system. He still doesn’t pretend to know the complexities of building a roster by navigating the collective bargaining agreement. Trading for an unwieldy contract and receiving draft picks as a sweetener in hopes of later flipping the picks for a star? He said he figured that out only this year, when the strategy helped the Clippers trade for George.

To get comfortable in his new job, he followed the playbook from his old one.

His experience keeping Silicon Valley competitors from poaching Microsoft’s backbone talent — software engineers — translated directly to the NBA, where he knew success depended on hiring and retaining the league’s best personnel. The ability to do so hinged on top players and executives believing the Clippers were an attractive destination — a distinction that had never been achieved in the team’s history. Sterling was known to heckle his own players, and he kept a small support staff to cut cost.

In the last five months, the Clippers have retained highly regarded consultant Jerry West, general manager Michael Winger, assistant general manager Trent Redden and coach Doc Rivers. And the team was chosen by Leonard, the reigning most valuable player of the NBA Finals and the top available free agent.

During the team’s July 1 free agency meeting with Leonard, Ballmer’s willingness to compete aggressively left a strong impression, according to a person who was there.

“I think everybody was shocked when he pulled off the Kawhi-PG deal, but it’s a good statement of how he thinks about it,” Taylor said. “You’re not going to win anything, be it Microsoft or be it basketball, without the best people in the best roles.”

Across the league, Ballmer’s plans to privately finance a new arena for the Clippers in Inglewood at a price of more than $1 billion turned heads as the type of deal only the wealthiest owner of a North American pro team could contemplate. So has his multi-million dollar offseason renovation of the team’s Playa Vista practice facility, a building still owned by Sterling that is scheduled to be vacated by the team in only five years.

However, changing perception about the Clippers has taken more than a willingness to write checks. Crucially, team employees said, Ballmer has been aided by an awareness that the rich and powerful people who own professional sports teams are not always prepared to acknowledge: Just because he’d enjoyed wild success in another industry did not mean he knew all the answers in basketball. He believes his value is in the questions he asks.

“Whether true or untrue, with wealthy people the perception is, ‘That guy, he probably has to be right about everything,’” said Lawrence Frank, the team’s president of basketball operations. “The thing about Steve, he has unbelievable humility. Which is such a rare trait when you have someone who’s achieved such success.”

Ballmer might not know everything about the nuances of constructing a roster, but he knows what he wants.

“Championships,” Frank said.

It’s on matters such as business and technology that Ballmer becomes an especially prominent and demanding voice in the room. For example, he long dreamed of heightening the experience of watching live sports broadcasts through software, but the notion had gone nowhere until shortly after he bought the Clippers, when he met a team of USC professors working on augmented reality software.

“A month and a half before the season we showed him all the stuff that we were doing,” Rajiv Maheswaran, the CEO of Second Spectrum, told The Times in February. “Steve’s like, ‘I want all this stuff for every Clippers fan tomorrow!’ We signed a deal and my [chief technical officer] flipped out because, ‘I got six weeks to make this thing before the start of the season!’”

The product was ready by opening night in the fall of 2014.

Five years later, the Clippers and the company — of which Ballmer is an investor — unveiled an even more ambitious project. An app called CourtVision takes data from motion-tracking cameras mounted in every NBA arena and runs it through software that allows Clippers broadcasts to be customized to each viewer’s liking. One mode diagrams plays as they happen. Another shows the probability of a shot being made based on each player’s location. Ballmer and Maheswaran believe it is the future of how audiences will watch live sports.

Ballmer’s hard-charging approach doesn’t always work, of course. He has drawn criticism for some of his actions, and his decisions have not always yielded success.

The team’s aggressive push to construct its own arena in Inglewood has led to multiple legal challenges and derision from Lakers owner Jeanie Buss, according to internal emails first reported by The Times in March. In April, a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge ruled that one such lawsuit, brought by a community group seeking affordable housing, may proceed. Madison Square Garden Co., the owner of the nearby Forum, remains locked in a contentious legal fight with a Clippers-controlled company, Murphy’s Bowl LLC, that is seeking to develop the arena. The Clippers are seeking to resolve the suits without litigation but are not backing down, Ballmer said.

On the court, the team has yet to advance to its first conference finals. Upon taking over as owner, Ballmer kept Rivers in his dual role of coach and president of basketball operations. But when trades and draft picks didn’t ultimately lead the team’s “Lob City” era to success, Rivers was stripped of his power to make personnel decisions.

The Los Angeles Clippers unveiled the first details and renderings of their proposed Inglewood arena, a billion-dollar project funded by owner Steve Ballmer.

As part of the course correction, Ballmer promoted Frank, a former NBA head coach and Clippers assistant whom he knew Rivers trusted deeply. Rivers has acknowledged the move allowed him to focus solely on coaching while ensuring trust between himself and the front office. In 2016, Ballmer gave Frank a year to study the best-run organizations in sports in order to eventually increase the staffing of what had been, under Sterling, one of the league’s smallest operations.

One agent, speaking anonymously because he has relationships throughout the league, said he was “shocked how well they’ve put together the organization.” Last month, Washington Wizards owner Ted Leonsis told the Washington Post that his team’s offseason restructuring was modeled on the Clippers.

When Frank proposed moves that were unconventional, such as poaching Sports Illustrated writer Lee Jenkins for a front office position, or carried significant risk, such as the trade of five draft picks, two players and two pick swaps for George, Ballmer posed questions but trusted the recommendations.

“The deal we made for Paul George? That’s a kind of ‘gulp’ deal,” Ballmer said. “‘Are we in on this thing?’

“People say, do owners make decisions? Well everybody’s got to be lined up on a decision like that. I’m super happy with where we are.”

Which explains why Ballmer stood on that rec center’s stage in late July, pumped his fists, raised the volume and talked of chasing the franchise’s first championship.

He was still speaking and gesturing excitedly as the phone of his former chief of staff began buzzing. Multiple people were sending Taylor a link to the video.

“My son even sent it to me,” Taylor said. “He said, ‘Wow, your ex-boss is pretty excited.’ I said, ‘That’s a Tuesday, man. That’s just him.’”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.