How a need to succeed fueled Austin Ekeler’s Rocky Mountain climb to the NFL

He arrived as the underdog — undrafted but hardly unloved by the Chargers — facing odds nearly as tall as he was, well, not so tall.

Back then, approaching six years ago now, Austin Ekeler was 5 foot 8 5/8.

Today, the Chargers list him at 5-10.

He’s still 5-8 5/8.

But nearly 7,000 yards, 59 touchdowns and countless celebratory strums of an imaginary guitar later, Ekeler’s height matters little compared to the long shadow cast by his heart.

A running back who can be so difficult to wrap up that even Ekeler’s drive has a stiff-arm, defensive coordinators NFL-wide are now forced to acknowledge a player every Power Five college ignored.

“All the stuff everyone’s seeing him do today,” said Jas Bains, Ekeler’s coach at Division II Western State, “he’s been doing since high school.”

Undersized and underestimated, Ekeler possesses a desire too large to be confined to a huddle, a want to succeed — no, a need to succeed — that’s impressive among even the most obsessed athletes on earth.

One way to express drive in football is by finishing plays. No one in the NFL has finished more plays in the end zone over the last two seasons than Ekeler.

His hunger runs so deep it once showed itself in perhaps the most graphic way possible.

As a rookie, his chiseled frame was stuffed with potential and nerves, so many nerves that after Ekeler stepped into his first huddle of his first practice in his first offseason session with the Chargers, he had to step back out — so he could throw up.

Suzanne Ekeler played small-college basketball in Colorado. She had post moves and a nickname. They called her “The Animal.”

“Apparently,” Ekeler said of his mother, “she was a maniac out there.”

Suzanne raised her two sons mostly on her own. Ekeler has never met his biological father, a man who was out of his life before Ekeler was born.

For a while, there was a stepfather, one who gave Ekeler a little brother, Wyett, and a significant aversion to manual labor.

Part of Ekeler’s upbringing included working on his stepfather’s 80-acre ranch in Briggsdale, Colo. — early and long hours tending to horses, cows and chickens, even in the windy, jarring freeze of winter.

“It was something he hated,” Suzanne said. “Both my kids hated it. But those chores, they had to be done.”

The stepfather also built fencing, which meant Austin and Wyett also built fencing, mile after mile of barbed wire. They’d spend their days pounding posts into the dirt and their nights sleeping in a camper.

Ekeler’s father is Black, his stepfather white, as is Suzanne. For a while, after it was just Suzanne and her two boys, folks would wonder about the makeup of the family.

“People would ask me if Austin was adopted,” Suzanne said. “I’d be like, ‘Nope. Absolutely not. I went through 27½ hours in labor for him. That’s my kid.’ ”

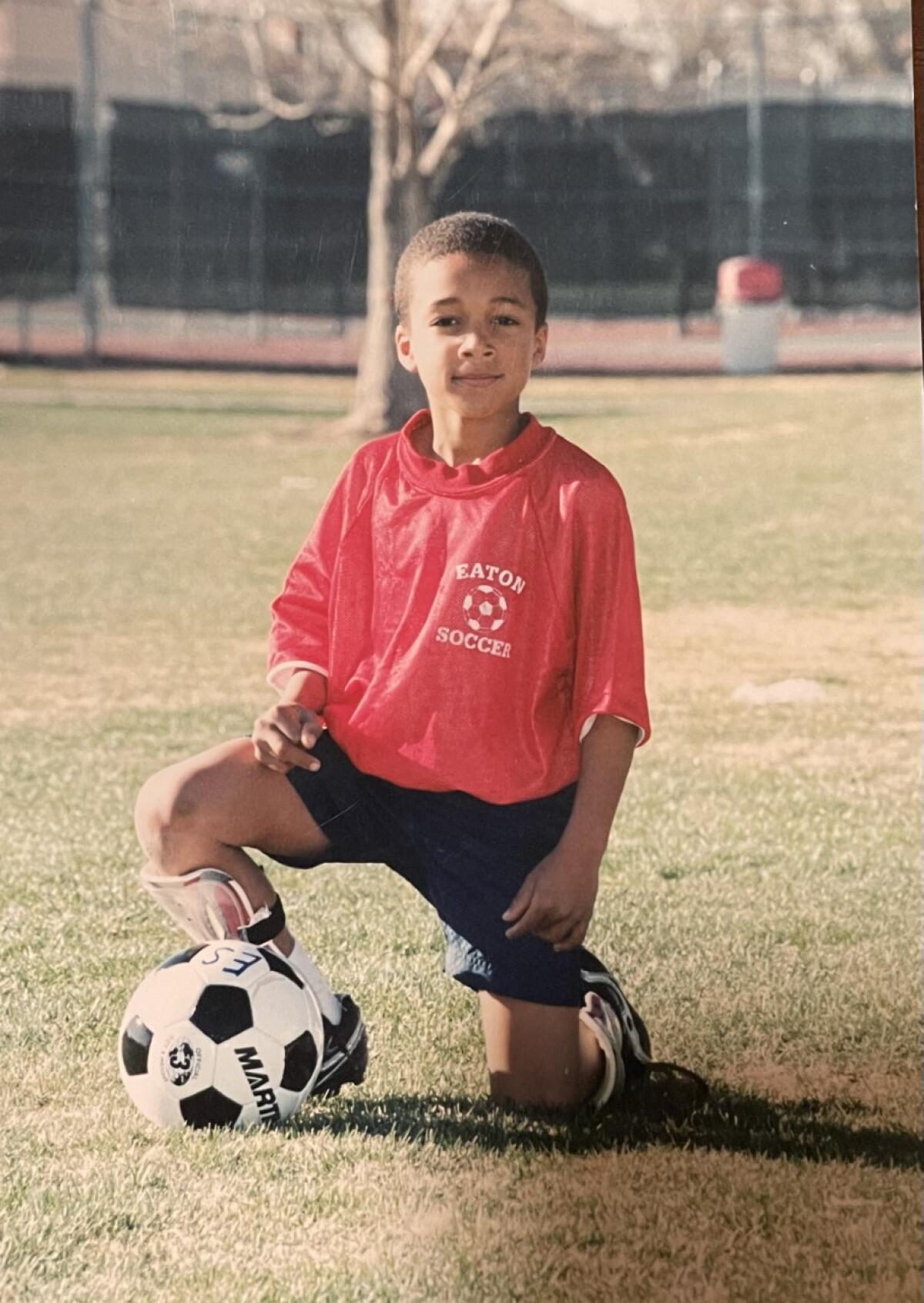

The three of them lived in Colorado’s northern plains, a little more than an hour from Denver, in Eaton, a single-story town with a Facebook page and a petting zoo.

Suzanne credited Eaton and her neighbors for helping raise Austin, calling the place “an amazing community that had our backs.” Austin repaid everyone in town by becoming a star athlete for the Eaton High Reds.

He was fast and strong and explosive, winning a state championship as a long jumper and accumulating football statistics so video game-ish that, still today, the numbers seem to grow each time the stories are retold.

Now considered one of the NFL’s strongest players pound for pound, Ekeler first learned about weightlifting while at Eaton High and about on-field toughness a little before that. In the summers when he was growing up, his mother would coach him in basketball.

One day, while trying to illustrate a certain inside move to the rest of the team, “The Animal” whirled and elbowed her first born in the face, blackening Ekeler’s eye.

“If you’re going to come through my paint, buddy,” Suzanne recalled, laughing, “you’re going to have to feel something.”

It would be years before Ekeler even pondered the NFL as a possibility. He didn’t grow up watching football. He watched rodeo, his stepfather involved in team roping.

When he was about 12, Ekeler tried bull riding — briefly — straddling animals that were actually calves. Yeah, just calves. Just angry, ornery calves.

“My bull-riding career lasted three bulls,” Ekeler said. “I got bucked off every one of them before eight seconds. And I was terrified the whole time.”

He had never heard of Western State before the school began recruiting him. Located in Gunnison, Colo., not far from Crested Butte Mountain Resort, Western’s football field sits at nearly 8,000 feet of elevation.

“It’s nowhere near anywhere,” said Tom McConnaughey, a former Chargers scout who was among the first to discover Ekeler. “If you don’t get there before the snow comes, you’re not getting there.”

Only a few small schools showed interest in Ekeler and Bains was the only coach who said he could remain at running back. Others wanted him to play in the secondary or sign as an athlete.

The same day he graduated from Eaton — one of 96 in his class — Ekeler packed his 2001 Chevy Silverado and drove up the mountain to Western, where he was working out with his new teammates by nightfall.

Just like in high school, he was a star from the start, a team captain and almost immediately the best player in the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference.

“He was the guy here,” Bains said. “We played as good as he played.”

There are pictures of Ekeler all over the school, which is now called Western Colorado University. In the administrative offices. The athletic offices. Bains’ office. Pictures and a jersey displayed so that Ekeler’s time there won’t be forgotten.

They still talk about his performance against Northern Colorado — 226 yards and two touchdowns — when he scored after being tackled, rolling over on top of a defender, regaining his feet and sprinting away from defenders who already had hit pause.

Cutting down the number of sacks on Justin Herbert will be among the Chargers’ priorities as they look to beat the Colts and clinch a playoff berth.

“He was dodging people just to take the handoff,” said McConnaughey, who now works for the Jacksonville Jaguars. “It was not a good team. It was watching him evade the first guy and the second guy and then trying to plow through the third and four guys. And he usually was able to do it.”

Before taking over at Western, Bains was an assistant at Chadron (Neb.) State when former Charger Danny Woodhead, another undersized running back, was there. McConnaughey recalled Bains describing Ekeler as “Woodhead 2.0.”

As Ekeler was readying for his senior season, Bains explained to him how favorably he compared to Woodhead and how NFL scouts were beginning to show interest.

Bains couldn’t be completely sure Ekeler would succeed as a pro but knew Ekeler had the proper wiring, something Bains witnessed often from his office overlooking the school’s indoor field house.

“We’d be in here on a Saturday getting some work done,” Bains said. “You’d look down into this facility — it’s just massive — all the lights are on and there’s one guy in there. Of course, it’s him.”

McConnaughey visited the school early in Ekeler’s final season, arriving on a day when the football team didn’t have practice. So Bains summoned Ekeler to his office to meet the scout.

They sat together for two hours watching tape. McConnaughey: “I’d never seen a kid do that” — the session including everything from Ekeler asking questions about the NFL to detailing his post-football plans of working in energy management.

McConnaughey said he left convinced Ekeler was “a squared-away guy” and had these parting words: “We gotta get you to camp somehow.” Over the next several months, McConnaughey called and texted Ekeler often.

Following his final college season, Ekeler knew his best shot at making it to the NFL was to give himself completely to football. So he left Gunnison and moved to Denver to train at Landow Performance with other prospects.

By that point, Ekeler was working with an agent, Cameron Weiss. One day, Ekeler called with an update on his training. The conversation went something like this:

Ekeler: “Do you know who Christian McCaffrey is?”

Weiss: “Well, yeah.”

Ekeler: “I’m doing as well as him in pretty much everything here.”

“My first reaction was, ‘This is real?’ ” Weiss said. “So I confirmed it with the trainers at Landow. They told me, ‘Yeah, Austin is freaky.’ ”

McCaffrey became the second running back drafted in 2017, going No. 8 overall to Carolina. In all, 245 more players were picked, including 25 running backs. None of them were named Austin Ekeler.

“All my life, I’ve seen people around me tapping out. And I’d be like, ‘No, we’re just getting started.’ ”

— Austin Ekeler, on perseverance

Instead, moments after the draft ended, Weiss took a call from the Chargers, who offered Ekeler $5,000.

Aware the team might have a spot for a running back and recalling how much interest McConnaughey had shown, Ekeler picked the Chargers over another team that offered him twice the money.

Asked now about that competing offer, Ekeler said he wasn’t aware of any of the details.

“Once the Chargers called, that was it,” he said. “I didn’t care what else was out there.”

He made the Chargers as a rookie, played himself into an increased role in his second year and, when Melvin Gordon held out to start the 2019 season, proved he could be a No. 1 back.

The Chargers can clinch a playoff spot with a win over the Colts on Monday night, but both teams have had their ups and downs during an uneven season.

Ekeler’s role expanded steadily but also quickly as he first seized and then squeezed dry his opportunity.

Beyond the end zone, the story was much the same, Ekeler understanding that the fleeting nature of football and the fame it can provide calls for a two-minute offense off the field too.

“All my life, I’ve seen people around me tapping out,” he said. “And I’d be like, ‘No, we’re just getting started.’ ”

As someone who eats up ground for a living, it seems natural that Ekeler always has had an interest in real estate. He began investing in rental property early, buying his first duplex heading into his second NFL season.

A few months earlier, he had received his first endorsement deal — $4,000 in credit he could use to buy anything he wanted from Adidas. Pretty soon, he was signing items for a memorabilia company for $1,000.

None of this stopped Ekeler from returning to school after his rookie season to complete his degree, a very real way for a “squared-away guy” to acknowledge football can’t last forever.

Into his second season, Ekeler’s social-media presence increased as he willingly engaged with fans — “I need that interaction,” he said — his popularity growing right along with his Charger stats, the numbers eventually making Ekeler as valuable in fantasy football as the real thing.

In mid-March 2020, the Chargers signed him to a four-year, $24.5-million contract that guaranteed him $15 million.

Just a few days later, COVID-19 shut down his budding world, leaving Ekeler thinking he’d survive on working out and playing video games until the restrictions were eased.

“I played video games for two weeks and went crazy,” he said. “I was like, ‘I can’t do this.’ I just can not sit still. I need to be building things.”

So he began sharing his workouts on Twitch. Ekeler started Gridiron Gaming Group, a streaming business that allowed athletes and celebrities to connect with fans while playing games such as “League of Legends.”

He kept accumulating real estate and established the Austin Ekeler Foundation on the same two principles upon which he established Austin Ekeler: create opportunity and fulfill potential.

“It would be really easy to play football and invest my money and just chill and grow a family,” he said. “That sounds terrible to me. And I’m like, ‘Why does that sound terrible?’ It’s because I have all these ideas in my head and if I’m not acting on them I feel like I’m lost.”

One of those ideas is “Eksperience,” an app designed to connect fans to athletes interested in expanding and monetizing their streaming presence. Ekeler has been working on the project for two years with hopes of launching it soon.

“Instead of having his walls up like most athletes do, Austin has his walls very much down.I cannot tell you another guy I’ve been around who holds himself out in that manner.”

— Cameron Weiss, agent representing Austin Ekeler

He hired a manager and works with a public relations firm, Sunshine Sachs, and a marketing company, Rubicon. Ekeler estimated that there are 10 to 15 people “helping me move this engine that I’ve been creating.”

He joined with a partner and now owns 115 rental properties in Colorado and Missouri. He moved his offseason home to Las Vegas for business purposes and installed a streaming studio there to match the one in his Orange County house.

“What really gives me substance in my life is when I’m building things,” Ekeler said. “There’s no concern about trying to do too much. I’m trying to make it too big. I’m searching for that.”

He is the star of “Ekeler’s Edge,” a fantasy football-themed show on Yahoo, and “Ekeler Dome,” an interactive competition series he livestreams.

Each week, he gives away two signed jerseys to people who have him on their fantasy teams, Ekeler announcing the winners himself in videos he records.

“Instead of having his walls up like most athletes do, Austin has his walls very much down,” said Weiss, the agent. “I cannot tell you another guy I’ve been around who holds himself out in that manner.”

Ekeler has done endorsement deals with more than 75 partners, literally eating (Chipotle), drinking (Anheuser Busch) and sleeping (Sleep Number) his way into becoming a promotional force.

But he does set limits. Ekeler doesn’t drink caffeine, so he has turned away coffee companies and energy drink makers. He doesn’t gamble, so he’s brushed aside those overtures, as well.

“Dollar signs are not in his eyes in that sense,” said Madison Dodson, Ekeler’s manager. “It has to be something he believes in and truly supports. He’s authentic to his core in everything he supports and does.”

Ekeler also has worked with Frito-Lay, which might seem an odd pairing given how eager his abs are to show themselves. But, get this: he loves Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. In moderation. Also loves Taco Bell the same way.

“Taco Bell’s my jam,” Ekeler said. “But I’m not eating it every flipping day or every week, you know?”

Ekeler’s social media presence never has been greater. His girlfriend, Melanie Wilking, is a dancer and content creator with 3.4 million followers on TikTok, where the two of them can be found dancing to routines she choreographed.

For their first date almost two years ago, Ekeler surprised her by taking her parasailing. Said Wilking, “I think he was more scared than I was.”

Ekeler is co-owner of a team in Fan Controlled Football and last year, for the first time, topped seven figures in endorsement earnings.

Still, away from the field, he lacks the flash he routinely displays on Sundays, a fact Dodson underlined by calling Ekeler “just a farm-town guy from Colorado.”

After signing his second contract, the only thing Ekeler splurged on was his white Corvette, a ride he coveted going back to a childhood of playing the video game “Need For Speed.”

During Super Bowl week last season, Dodson said she kept noticing all the diamonds and sparkles decorating other NFL players. She turned to Ekeler one day and said, “We gotta get you a necklace.”

He shook his head.

“No,” Ekeler told her, “I gotta get myself more real estate.”

Suzanne rarely misses either of her sons’ games, Wyett now a safety at Wyoming, where he gets around town in his big brother’s old Chevy Silverado.

She used to sit in a lower, corner section of SoFi Stadium, along with the families of other Chargers. But then, one game, she missed her boy scoring a touchdown in the opposite end zone. The next week, Suzanne moved up a level.

Now, in Section 212, she’s the one wearing the No. 30 “MAMA EK” jersey in the front row, unfurling the Ekeler flag and waiting to exchange knowing waves with her son after he trots onto the field for warmups.

“When I sit back and watch him now, I’m just so thankful that the world gets to see what I’ve seen for so long.” Suzanne said. “I’m so darn proud of him.”

Plucked from the top of a Colorado mountain, more than a mile in the air and with aspirations even loftier, Ekeler continues to chase all that’s possible — on the field and off — and maybe some things that aren’t. But, then, why not?

“I don’t want to crash and burn and have everything crumble down,” he said. “I don’t want things to be catastrophic. But I’m trying to test myself and push as hard as I can. What’s the worst thing that could happen? I could learn.”

Yeah, he came down from a peak, Austin Ekeler did, fully intent on building a mountain of his own.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.