Angels’ Mickey Moniak finding his baseball groove after years of struggles

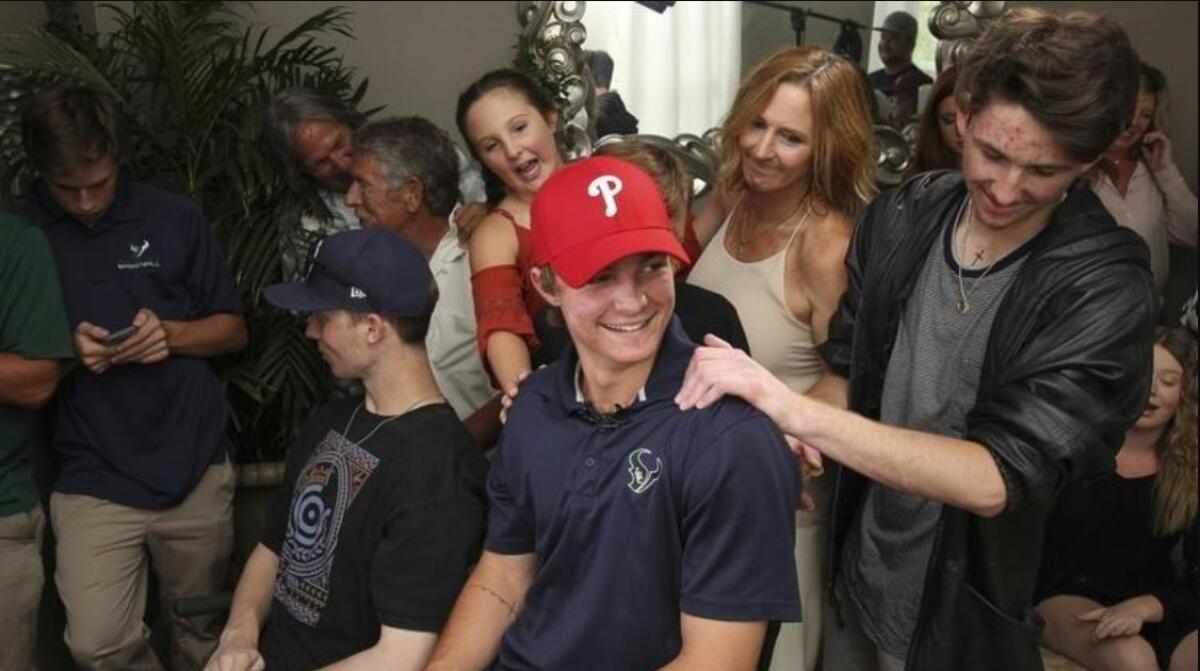

The full armada had arrived in Encinitas, anyone who was anyone in the 2016 Philadelphia Phillies’ front office flying into a humble beach city to see the boy who was tearing through San Diego.

The Phillies had the first pick in that year’s draft, and La Costa Canyon’s Mickey Moniak was almost assuredly their guy. So former Phillies manager Charlie Manuel was there, La Costa Canyon coach Justin Machado remembered, and executive Pat Gillick, and a platoon of top scouts for a normal-as-day April high school baseball game.

“It was crazy,” Moniak’s father, Matt, recalled. “We still barely talked about it, because [Mickey] was so right into pro ball.”

Seven years later, when asked about that day in front of his Angel Stadium locker, the 25-year-old outfielder just shrugged. His cap perched backwards, and hands slung in pockets. Moniak is disarmingly nonchalant — the honest kind, not dismissive, the kind that comes from growing up in sandals-and-board-shorts Encinitas.

Expectations, he pursed his lips, are expectations. Folks are going to have them — when you get scouting directors showing up to every high school practice, when you get 80 scouts watching your batting practices, when you become one of 59 first-round draft picks in history.

“To be honest with you, I mean, I knew they were coming,” Moniak said, remembering that April 14 day playing in front of the Phillies’ brigade. “But I didn’t think twice about it.”

Shohei Ohtani said Friday he will do anything to help the Angels reach the playoffs. The Angels should help him instead of trading him.

That day, Moniak hit for the cycle, went five for five and with eight RBIs.

“Just a regular Mickey day,” Machado said.

There is a longtime slogan in the La Costa Canyon program, drawing a smile from Moniak when asked about it: “Just Cruisin’.” It is quite literal, to him; just how they roll. Just how he rolls years later, cruising through years of inconsistency and injury as the baseball world soured enough on his upside to dangle him for a Noah Syndergaard half-year rental at last year’s deadline.

His blazing start this season, finally given consistent playing time, made some sense. His domination a hundred plate appearances later — he’s batting .331 in 169 at-bats — makes less. He is attacking pitches without abandon, walks a complete afterthought, jumping on pitches in the zone to the tune of 11 homers and a .977 on-base-plus-slugging percentage.

Is that truly sustainable, an approach so dominated by natural hand-eye coordination, an approach that draws its sword and stares down against hordes of modern analytical thinking on batted-ball luck? Probably not. But ask Machado: That approach has been the same since his high school days. Same as his personality.

And now, at least, the belief Moniak’s held for years is evident: Success is in there. In him.

“I’ve definitely tried to … handle life when it comes at me,” Moniak said. “Try to be where my feet are.”

Since Moniak started playing an hour from home, his family usually sits in the second-to-last row in section 209 at Angel Stadium.

A while back, Matt said, former Angels player and longtime manager Bobby Valentine came to a game and sat in the row directly behind them. The two men struck up a conversation — Valentine telling Moniak’s father how happy he was for his son’s success.

“I almost got all teary — I’m like, ‘It’s been a long hill, Bobby,’ ” Matt said. “He’s like, ‘I know.’ ”

The Angels failed to capitalize on bases-loaded opportunities in the fourth and ninth innings as their winning streak ended in a loss to the Pirates.

The numbers were never really there through six years in Philadelphia, through mechanical tweaks Moniak felt “didn’t work out” with his ability to cover offspeed pitches. After he finally made the opening day roster last season, he broke his hand.

“His demeanor never changed,” Machado said, mentioning that Moniak comes back to Encinitas in the offseasons to work out multiple times a week. “He was always rock-solid. He knew that eventually it was gonna happen for him — just being [the first pick], they expected now. And he understood that it didn’t have to be that.”

A change of scenery, Moniak felt, made sense for both parties. Working with Angels hitting coaches Phil Plantier and Marcus Thames in the offseason has helped him load into his left hip better at the plate, opening his stance for better fastball coverage and adjustment to offspeed pitches.

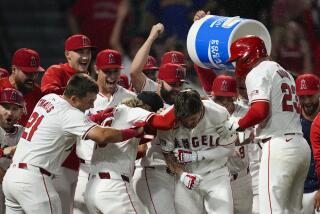

But the strikeout-walk numbers are almost comically bad — five walks against 56 strikeouts after Sunday’s 7-5 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates. The reason is intricately complex: Moniak doesn’t like walking. Never has, dating back to high school. He will chase pitches, he admits, because he trusts he can hit.

Does manager Phil Nevin want him to walk more? Sure. But what isn’t broken need not be fixed.

“He’s still gonna chase balls, and I’m fine with that,” Nevin said. “He’s so aggressive when he gets up there — I don’t want to change that, because he’s got such good hand-eye coordination … that’s what all his data and statistics are showing right now.”

Life has brought its ups and downs, but the most upset Machado’s ever seen Moniak is when he beat him at a round of golf.

The truth, from Moniak, his father, Machado and others: Kid just hasn’t changed much from when he was 17. Just cruisin’.

For the record:

9:07 a.m. July 24, 2023An earlier version of this story misidentified Mickey Moniak’s father as Mike. His first name is Matt.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.