Pregnant people of color more likely to get procedures they didn’t consent to, study finds

A new study provides a sweeping look at how birthing experiences differ dramatically for pregnant people of color compared with pregnant white people.

Black, Indigenous and other people of color giving birth were more likely than white people to experience health providers coercing them to go along with procedures they did not want, or to have their lack of explicit consent disregarded altogether, according to a new study.

The new research, published Thursday in the journal Birth, provides a sweeping look at how birthing experiences differ dramatically for pregnant people of color compared with pregnant white people.

For instance, the study reported that 51% of BIPOC people surveyed said they received nonconsented procedures — such as getting an epidural or drugs to speed their labor— during perinatal care or while having a vaginal birth that they did not consent to. The corresponding figure for white people was 36%.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia’s Birth Place Lab and UC San Francisco showed that while BIPOC and white people would decline care at the same rate, health providers were more likely to respect the wishes of white people.

Black patients were the most likely to have their wishes ignored even after declining a procedure. Compared with white patients, they were 89% more likely to have nonconsented procedures during perinatal care and 87% more likely to have them during vaginal births. People who identified as Asian, Latinx, Indigenous or multiracial reported experiencing pressure to accept perinatal procedures 55% more often than white people.

Among all people who had vaginal births, 40% reported experiencing nonconsented procedures.

In humans, the distance between the brain and heart can be a foot or more.

The study authors analyzed data from the Giving Voice to Mothers study, which recorded the pregnancy and birth experiences of 2,700 people in the U.S. between 2010 and 2016. They used survey responses from a subset of more than 2,400 participants who had nonconsented procedures or felt they were pressured to take medication to start or speed up labor, use an epidural or take medicine for pain relief, begin continuous fetal monitoring, or have an episiotomy.

Overall, participants who had caesarean sections were 30 times more likely to report pressure from providers than those who eventually had vaginal births. Researchers noted that they did not find racial or ethnic difference in the experience of pressure to have a C-section.

The goal of the study was “to collect data from populations that have not previously been included in studies on the experience of childbirth,” the researchers wrote, and they partnered with organizations to “intentionally oversample from communities of color and those who chose to give birth in the community.”

“We often need this quantitative data ... to explain what the community understands and knows,” said study leader Rachel G. Logan, a postdoctoral scholar in UC San Francisco’s department of family and community medicine.

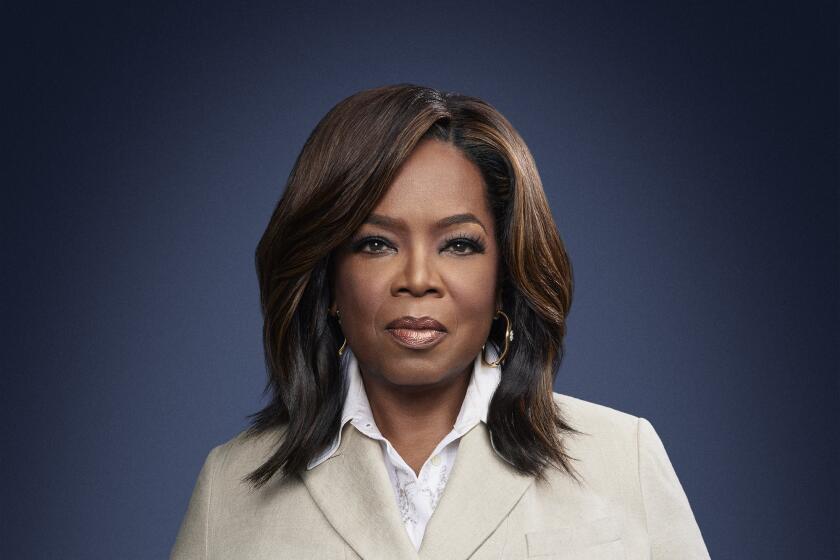

Ahead of a new documentary about racial inequities in healthcare, the TV host opens up to The Times about her own experiences.

She said too often the onus is put on birthing people instead of health providers to change their behaviors in order to receive better service. In her research looking at people’s experiences of sexual and reproductive healthcare using a reproductive justice framework, she has found that Black and brown people who try to advocate for themselves “may be misconstrued as them being

aggressive.”

Part of the problem is health systems offer few if any avenues for accountability when patients of color experience racism in health service settings, Logan said. While she’s not opposed to tips on how patients can advocate for themselves, “this idea that patients can overcome structural racism really misses the mark of talking about the root cause of the issue in the first place.”

“Something I have heard consistently when we’re talking about health services research is, especially because I do work with Black women, is, ‘What should they do to be better patients?’” Logan added. “I think it might fall sometimes into respectability politics — ‘Do your research beforehand,’ ‘Dress a certain way,’ ‘Speak in a certain manner.’ ... By and large, that won’t save us.”

The new study comes amid a push by medical schools, health providers and public health experts to address racism and racial health disparities throughout the system, from doctor’s offices to hospital emergency rooms. While some researchers and medical providers sounded the alarm in the decades before, the COVID-19 pandemic, George Floyd’s death and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calling racism “a serious public health threat” have focused attention on how to address prejudice, bias and racism in health.

It took years for the American Public Health Assn. to say that police violence threatens the health of not just victims and their families, but entire communities.

In the Birth study, Logan and her colleagues found that participants who had a midwife or planned birth outside of a hospital, a greater number of prenatal care visits, or the same health provider throughout their pregnancy were less likely to experience pressure or nonconsented procedures. But even then, they found people of color were still consistently experiencing pressure.

Overall, 31% of all respondents were pressured to accept perinatal procedures, 41% received nonconsented procedures, and 10% were pressured to have a C-section

Saraswathi Vedam, a professor of midwifery at Canada’s University of British Columbia and one of the study’s authors, said the team’s earlier research found that 17% of pregnant people experienced mistreatment, including being shouted at, being scolded, having their requests for help denied or ignored, and being threatened that something bad will

happen to them or their baby.

Vedam said the new findings were “distressing” because they show “the health system is not protecting people’s human rights.”

“This particular paper is probably the most jarring because you’re talking about people having things done to their bodies, or their babies without their involvement or their consent or being pressured into things and ... are pressured based on their identity,” she said.