Q&A: How a Florida judge’s mask ruling could cause problems in the next pandemic

When a federal judge struck down a nationwide mask mandate for passengers on planes, trains and other forms of public transportation, she abruptly halted one of the pandemic’s most hotly contested public health measures.

The order issued Monday by U.S. District Judge Kathryn Kimball Mizelle in Tampa, Fla., also upended the agency responsible for protecting the pub-lic’s health. It’s not often that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s authority to curb disease threats is called into question.

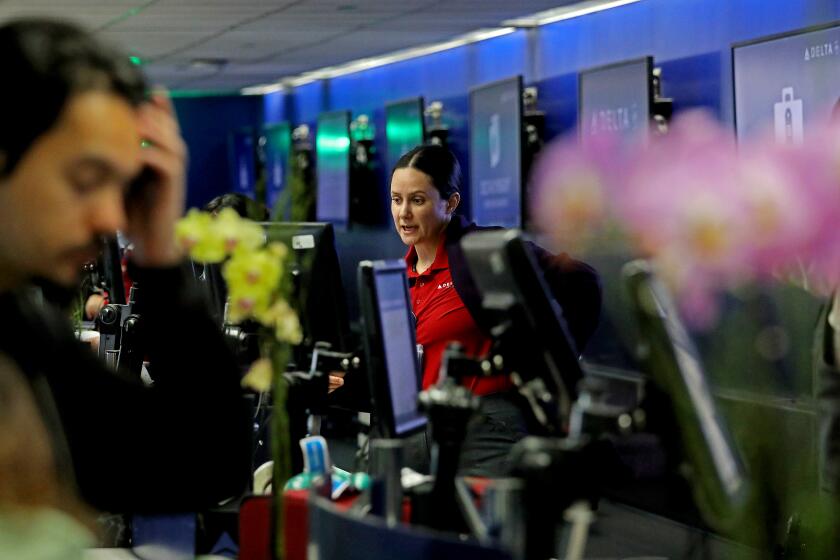

The Justice Department appealed the order late Wednesday after the CDC determined that “requiring masking in the indoor transportation corridor remains necessary for the public health.” In the meantime, airlines, airports, Amtrak and public transit systems across the nation have stopped requiring travelers to mask up.

What’s at stake? A lot more than meets the eye, legal experts say.

Here’s a closer look at the issues involved.

Why did the CDC require travelers to mask up in the first place?

Travelers using public transportation play a key role in a pandemic caused by a respiratory virus that spreads easily from person to person. They come from a variety of communities, converge on crowded trains, planes and buses, and are often packed tightly together for long periods. After mixing with a random assortment of strangers, they emerge in new settings where they make contact with a whole new set of people.

It’s an optimal formula for spreading a virus broadly and unpredictably across geographic boundaries.

Many medically vulnerable people are worried about how to handle public transportation now that a federal judge has struck down the CDC mask mandate.

Public health law gives cities, counties and states the lead role in controlling the spread of disease within their borders. But public transportation systems routinely cross city limits, county boundaries and state borders. When a hazard can easily and invisibly cross jurisdictions, a federal agency typically is granted authority to step in and coordinate a standard response to contain the hazard or slow or stop its spread.

The CDC didn’t use this power during the Trump administration, which generally opposed mandates to control the virus. But once President Biden was in the White House, the CDC exercised its legal authority.

On Jan. 29, 2021, the agency issued an 11-page order requiring the wearing of masks by passengers and operators of “public transportation conveyances or on the premises of transportation hubs to prevent spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.” It covered airplanes, most ships, ferries, trains, subways, buses, taxis and ride-shares such as Uber and Lyft.

But why keep it going after so many states and counties dropped their mask rules?

That’s what airline executives and GOP lawmakers wanted to know. In early April, when new infections across the U.S. were as low as they’d been since July, they demanded that the CDC end its travelers’ mask mandate.

But one nagging worry stayed the hand of the CDC. A new subvariant of Omicron called BA.2 was appearing to spur a run-up in cases, and on April 13, the agency declared it wanted to assess whether BA.2 would put new pressure on hospitals or cause a spike in COVID-19 deaths.

At least until May 3, the CDC said, travelers would have to keep masking.

So the Florida judge just brought the mandate to an end a little sooner. What’s the big deal?

The judge’s order to void the mask mandate could profoundly weaken the CDC’s practical and legal authority to act in a national emergency, said Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University expert on public health law.

That emergency could be years down the road. Or it could occur in the next few months if the coronavirus spins off a new variant that spreads even more readily, evades the protection of medicines or vaccines, or proves to be a more efficient killer.

The Justice Department is filing an appeal seeking to overturn a judge’s order that voided the federal mask mandate on planes, trains and travel hubs.

Over the last two years, the CDC has tried to use some legal authorities that were “at the edge of its powers,” Gostin said. For instance, when it attempted to bar evictions because keeping people in their homes would make it more difficult for the virus to spread, the agency faced legal challenges and had to relent.

By contrast, the CDC’s authority to suppress interstate transmission of a deadly virus in the midst of a pandemic “is not peripheral,” Gostin said. “It’s not marginal. It’s not even a debatable case.” It’s a central power granted under the 1944 Public Health Service Act.

If the CDC can show that masks limit viral transmission, but cannot require passengers on public transportation to wear them, “then it can do nothing,” Gostin said.

Will everything be OK now that the Biden administration has appealed the Florida judge’s decision?

Actually, the appeal could place the CDC in deeper peril.

Now that the Justice Department has asked a higher court to weigh in, the case will go to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which has jurisdiction throughout Florida, Georgia and Alabama.

Gostin called Mizelle’s ruling “a devastating opinion — one of the more ruinous federal court opinions I’ve seen” in the public health sphere. But as a decision by a single judge in a federal district court, it has limited power to set a new precedent weakening the CDC’s authority.

Right now, with the virus causing so much less trouble than it did just a few months ago, the case for upholding a mask mandate is pretty weak. The appeals court might well let Mizelle’s order stand.

If the U.S. public health emergency ends, Americans would be vulnerable to a new coronavirus variant that sparks another COVID-19 surge.

That court might not intend to endorse the judge’s “extraordinarily narrow and miserly interpretation of what CDC has the authority to do,” Gostin said. But a stay could give her ruling the weight of legal precedent in a future public health emergency, he said.

“Legal conservatives should be careful what they wish for,” Gostin said. One day, COVID-19 or some other catastrophic disease will threaten Americans’ lives and safety. “They won’t want a public health agency responding to it with their hands tied behind their backs,” he said.