If you take an at-home coronavirus test, who keeps track of the results? Probably no one

The wildfire-like spread of the Omicron variant may have inspired you, like many Californians, to snap up a few rapid coronavirus test kits — if you could find them, that is.

And when you started worrying that you’d caught the coronavirus, you may have put one of those kits to use. You carefully swabbed the insides of both nostrils, mixed your sample with a few drops of reagent, placed it on a test strip and waited 15 minutes to see your results.

But after doing all that — and gasping with either relief or dismay — you may have overlooked the kit’s last instruction: to report your results.

Some test kits advise you to call your healthcare provider. Others want you to use the test maker’s app.

“Home testing leads to marked underestimates of case numbers,” Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of UC San Francisco’s Department of Medicine, said in an email. “Clearly many hundreds of thousands of people are now diagnosing themselves with positive home tests (generally plus symptoms) and these are not reported.”

Even if you do try to report your results, the information isn’t likely to move the needle on the public’s understanding of the virus. That’s because they’re not included in the data health officials use to produce their reports and policies.

So the more people test themselves at home, the less the official numbers about new infections and positivity rates (that is, the percentage of tests that detect the virus) will provide an accurate picture of the public’s health.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing — it’s just a cautionary note about the data we rely on as we chart a path through the pandemic.

The explosive increase in U.S. coronavirus case counts is raising alarm, but some experts believe the focus should instead be on hospital admissions.

Experts say there’s always been a disconnect between the reported coronavirus case counts and the truth. Because many people who catch the virus experience few or no symptoms, many infections go unreported.

Similarly, test positivity rates tend to be inflated because the people most likely to show up at a testing center are the ones with COVID-19-like symptoms. Large organizations that require all their members to be tested regularly invariably have lower positivity rates than sites that test only people who think they might be sick.

Testing more people more often, as a number of other developed countries do, could help identify outbreaks and limit their spread. But for a variety of reasons, a growing reliance on at-home rapid tests kits may not help public health officials in their battle to track and understand the pandemic.

There are a number of situations that might prompt people to test themselves. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests taking a self-test “if you have COVID-19 symptoms or have been exposed or potentially exposed to an individual with COVID-19.” (The symptoms to look out for, the CDC says, include fever or chills, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue and sore throat.)

Another good self-test time, the agency advises, is before gathering with people who are at greater risk of being infected, such as those who are unvaccinated, elderly or have weakened immune systems. Or maybe you want to attend an event that requires proof of a negative test.

What do you do after you take the test? If it comes back positive, health officials say you should isolate at home, alert the people with whom you’ve been in close contact, and tell your healthcare provider. The L.A. County Department of Public Health also has a hotline for you to call — (833) 540-0473 — if you have questions, need referrals or need help in notifying your close contacts.

A department spokeswoman said that “we will be documenting and interviewing those that do call us with positive results.” But the department does not want to be contacted about negative test results.

COVID-19 just broke its year-old record for new U.S. infections in a week. But this time, far fewer hospitalizations and deaths are likely to follow.

Nor are health officials generally including the home test results in the confirmed case counts. One reason is that the low-cost rapid tests are antigen tests, while clinics and county test centers use polymerase chain reaction tests, which are better at detecting infections in their early stages. Then there’s the question of whether people taking tests at home are using them correctly or reporting the results accurately.

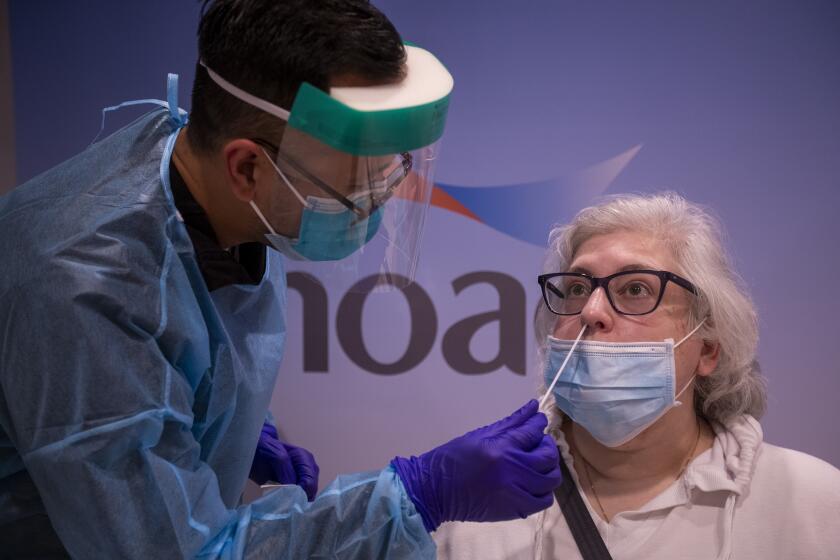

“Verification of results is a huge issue” for rapid at-home tests, said Gigi Kwik Gronvall, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. That’s why if you need a coronavirus test result to board a plane, she said, “you either need to have a PCR test that was done in a lab or you could go to a site that could give you [an antigen] test but it’s verified — somebody’s doing it for you and they see it’s done correctly.”

After some initial mix-ups, states are now reporting any antigen test results they collect separately from PCR results, Gronvall said.

Dr. Sara H. Cody, Santa Clara County’s health officer and public health director, agreed with Wachter that the new infections reported by health officials each day are “an undercount.” But that may not be as big a drawback as it would have been at the start of the pandemic.

Back then, Cody said, health officials “followed every case so carefully” because “it really, really mattered in our understanding of the pandemic and informing our policy choices.” But now, she said, “we’re in a place in the pandemic that’s quite different.”

Even with limited testing, officials know that case counts will increase rapidly because of the Omicron variant. “What’s most important to us now,” she said, “is that we measure our hospital resources” to make sure people who need acute care can get it. And with vaccination and booster rates high in her county, Cody added, it’s hard to tell at this point how many of the newly infected there will eventually need a hospital bed.

Early research points to mutations in the spike protein. But much remains unknown or unconfirmed.

Wachter, Cody and other health experts said policymakers’ focus is shifting away from the reported case counts to other measures, such as hospitalizations and positivity rates. Granted, positivity rates are thrown off by the exclusion of at-home test results. But Cody said it’s still meaningful to have an apples-to-apples comparison of positive test rates over time.

Santa Clara County has been doing around 20,000 tests a day, and its positivity rate was around 1.5% in early December, Cody said. As of Tuesday, she said, it was nearly 10.5%.

Despite the data issues they create, at-home antigen tests are still an important complement to PCR tests, Cody said. They alert people who need to isolate and “reduce the chances that they are going to go on and infect others, which is important broadly to public health.”

Besides, the L.A. County health department says, coronavirus case counts aren’t as meaningful as the trends they reveal.

“As is true with many reportable diseases, the reported numbers have never captured all cases,” a department spokeswoman said. “But they have provided trendlines for us to better understand what is happening and to contribute to modeling what is likely to be the most accurate numbers.”