Vaccine makers race to update their COVID shots, just in case

Vaccine makers are racing to update their COVID-19 shots so they’re a better match against the Omicron variant, the newest coronavirus threat. It’s not yet clear that a change will be needed, but they’re putting in the work — just in case.

Experts doubt current shots will become useless, but they say it’s critical to see how fast companies could produce a reformulated dose and prove it works. Even if existing vaccines hold their own with Omicron, scientists are certain this new variant won’t be the last.

Omicron “is pulling the fire alarm. Whether it turns out to be a false alarm, it would be really good to know if we can actually do this — get a new vaccine rolled out and be ready,” said E. John Wherry, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

It’s too soon to know how vaccines will hold up against Omicron. The first hints this week were mixed: Preliminary lab tests suggest two Pfizer doses may not prevent an Omicron infection but they could protect against severe illness. And a booster shot may rev up immunity enough to do both.

Better answers are expected in the coming weeks, and regulators in the U.S. and other countries are keeping a close watch. The World Health Organization has appointed an independent scientific panel to advise on whether the shots should be reformulated because of Omicron or any other variant.

But authorities haven’t laid out what would trigger such a drastic step. Would it be warranted if COVID-19 vaccines stop preventing serious illnesses? What about if a new variant merely spreads faster?

“This is not trivial,” Ugur Sahin, BioNTech’s chief executive, said shortly before Omicron’s discovery. A company could apply to market a new formula, “but what happens if another company makes another proposal with another variant? We don’t have an agreed strategy.”

In a large study, the risk of a breakthrough infection was 10 times lower for people who got a COVID-19 booster shot than for people who hadn’t.

It’s a tough decision — and the virus moves faster than science. Just this fall the U.S. government’s vaccine advisers wondered why boosters weren’t retooled to target the highly transmissible Delta variant — only to have the next scary variant, Omicron, be neither a Delta descendant nor a very close cousin.

If vaccines do need tweaking, there’s still another question: Should there be a separate Omicron booster or a combination shot? And if it’s a combo, should it target the original strain along with Omicron, or the currently dominant Delta variant plus Omicron?

COVID-19 vaccines work by triggering production of antibodies that recognize and attack the spike protein that coats the coronavirus, and many are made with new technology flexible enough for easy updating.

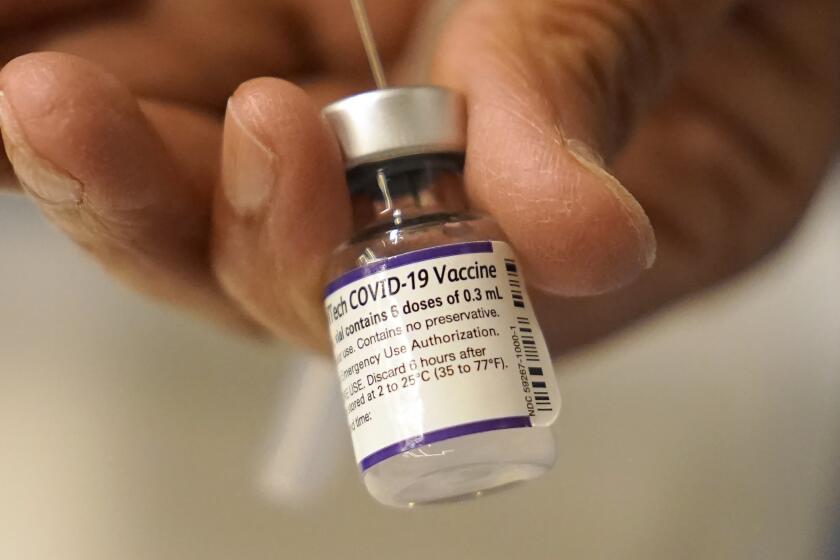

The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are fastest to tweak. They contain genetic instructions that tell the body to make harmless copies of the coronavirus’ spike protein, and the messenger RNA that holds those instructions can be swapped to match new variants.

Pfizer said it expects to have an Omicron-specific candidate ready for the Food and Drug Administration to consider in March. Some initial batches should be ready to ship around the same time, said chief scientific officer Dr. Mikael Dolsten.

Pfizer says a booster dose of its COVID-19 vaccine may protect against the new Omicron variant, which early indications show might be more contagious.

Moderna is predicting it will take 60 to 90 days to have an Omicron-specific candidate ready for testing.

Other manufacturers that make COVID-19 vaccines using different technology, including Johnson & Johnson, are also pursuing possible updates.

Pfizer and Moderna already have created experimental doses to match Delta and another variant named Beta. Those shots weren’t needed, but their development offered valuable practice.

So far, the original vaccines have offered at least some protection against variants. Even if immunity against Omicron isn’t as good, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top U.S. infectious disease expert, said he hopes the big antibody jump triggered by booster doses will compensate.

Pfizer’s preliminary lab testing, released Wednesday, hinted that might be the case, but antibodies aren’t the only layer of defense. Vaccines also spur T cells that can prevent serious illness if someone does get infected, and Pfizer’s first tests showed, as expected, that those don’t seem to be affected by Omicron.

Omicron’s impact on the COVID-19 pandemic will depend on a variety of factors that will take days to weeks for scientists to untangle.

Also, memory cells that can create new and somewhat different antibodies are formed with each dose.

“You’re really training your immune system not just to deal better with existing variants, but it actually prepares a broader repertoire to deal with new variants,” Dolsten said.

How aggressive a variant is also plays a role in deciding whether to reformulate the vaccine. Omicron appears to spread easily, but early reports from South African scientists hint that it might cause milder infections than previous variants.

The FDA has said companies won’t need to conduct massive studies of tweaked vaccines, just small ones to measure if people given the updated shot have immune responses comparable to the original, highly effective shots.

Wherry said he doesn’t expect data from volunteers testing experimental Omicron-targeted shots until at least February.

COVID-19 vaccines adapted for new coronavirus variants can receive authorization from the Food and Drug Administration without repeating full clinical trials.

Flu vaccines protect against three or four different strains of influenza in one shot. If a vaccine tweak is needed for Omicron, authorities will have to decide to whether to make a separate Omicron booster or add it to the original vaccine — or maybe even follow the flu model and try another combination.

There’s some evidence that a COVID-19 combo shot could work. In a small Moderna study, a so-called bivalent booster containing the original vaccine and a Beta-specific dose caused a bigger jump in antibodies than either an original Moderna booster or its experimental Beta-specific shot.

Scientists already are working on next-generation vaccines that target parts of the virus less prone to mutate.

Omicron brings “another important wake-up call,” Wherry said — not just to vaccinate the world but create more versatile options to get that job done.

AP reporter Jamey Keaten contributed to this report.