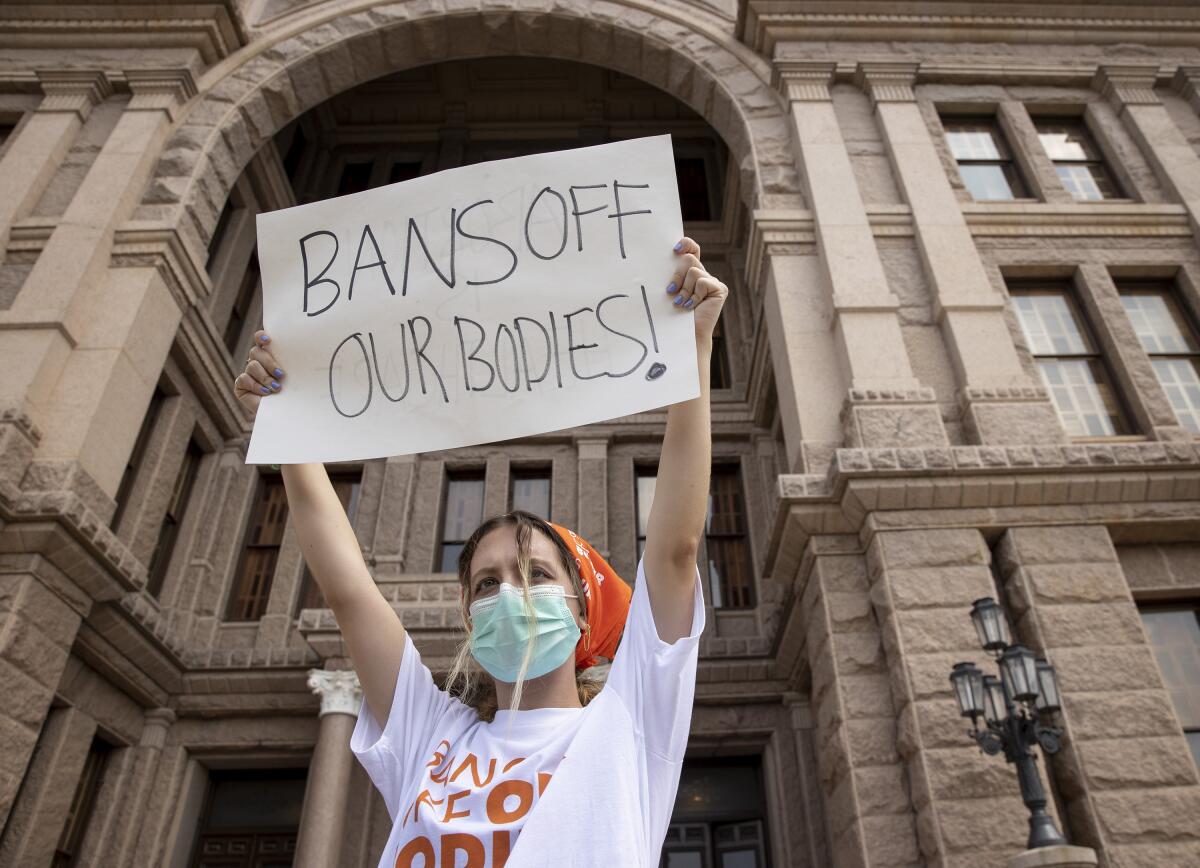

The Texas abortion law and what ‘6 weeks pregnant’ actually means

Though many have described the controversial new “Texas Heartbeat Act” as a ban on abortions six or more weeks into a pregnancy, that’s not precisely what the law says. Nor are its prohibitions triggered by actual fetal heartbeats.

As of Thursday, the law is being challenged by the U.S. Justice Department on the grounds that it violates the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution.

The text of the Texas legislation bans physicians from inducing an abortion after the detection of fetal cardiac activity or the “steady and repetitive rhythmic contraction of the fetal heart within the gestational sac.” In practice, electric impulses from a developing embryo can be detected by ultrasound at or around six weeks’ gestational age. So the law functionally bans abortion around that point, even though that’s long before a fetus develops a real heartbeat.

And despite Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s assertion this week that the law “provides at least six weeks for a person to be able to get an abortion,” that’s not the case either. In reality, even a woman (or transgender or nonbinary person) closely monitoring her menstrual cycle and testing will have learned about her pregnancy no more than about two weeks before the law’s prohibition kicks in.

Here’s why: Pregnancy as doctors measure it typically lasts 40 weeks, or about 10 months, not nine months. That’s because they start the clock on the first day of the woman’s last menstrual period before the pregnancy, even though at that point the egg and sperm are still weeks away from meeting. So on the first day of what will be described as your “pregnancy,” you are definitively not at all pregnant.

The Justice Department sues Texas to block the state’s abortion law that bans the procedure after about six weeks, which it contends is an unconstitutional prohibition.

Here’s a brief overview of how those first six weeks play out in an average cycle.

Week 1: On the first day of a period, which begins the cycle, the uterus sheds the lining it built up in anticipation of a pregnancy the previous month.

Week 2: The body prepares to release one or more eggs via ovulation.

Week 3: In a cycle when someone would become pregnant, the sperm and the egg meet up around the start of this week. About five to 10 days after that, the fertilized egg — which has now developed into an embryo made up of several hundred cells — implants in the uterus. After that happens, the body starts to produce human chorionic gonadotropin, a chemical that is detected by pregnancy tests. But it will take a few more days before even the most sensitive tests can detect a measurable amount in urine.

Week 4: If a woman is not pregnant, the end of week four — about 28 days after the first day of her period — is when she gets her period again, and the cycle starts over. People who are actively trying to get pregnant often begin testing around this time, maybe a day or two before an anticipated period.

Most people are not trying to get pregnant every month of their lives. And plenty of people who menstruate don’t have perfect 28-day cycles. A period being a few days late isn’t something a lot of people would even notice. Medical conditions, stress, certain types of contraception or even a recent COVID-19 vaccination can all interfere with a menstrual cycle. Some people just naturally have cycles that last 30 days, or 35 days, or 40, or more.

Another complication: Bleeding a little is not abnormal in early pregnancy. A person might notice spotting and assume she’s gotten her period. It could be days, weeks or even months before she realizes it wasn’t menstrual blood. In fact, many of the common symptoms of early pregnancy — bloating, fatigue, hunger, sore breasts — can easily be mistaken for signs of an impending period.

“It’s very common for people to not be tracking their periods to the day, and many do not have a regular cycle. It is really common for people to not know they are pregnant until after six weeks,” wrote Nisha Verma in an email. Verma, the Darney-Landy fellow at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, is an obstetrician-gynecologist and a family planning specialist.

So the earliest a woman could know she’s pregnant is perhaps a day or two before she is technically “four weeks pregnant” under the Texas law. The embryo has existed for maybe two weeks. That gives even the people most closely tracking their cycles about two weeks, if that, to seek to terminate a pregnancy.

For people who are seeking to get pregnant, calling their OB-GYN’s office with news of a positive test often results in a surprise: The doctor doesn’t want or need to see you right away.

“It is pretty common for us to wait until about eight weeks before bringing people in for their first prenatal visit, as long as they are not having particular issues like bleeding or severe nausea and don’t have underlying medical conditions that we are concerned about. This is because, honestly, there is just not much for us to do or assess earlier than eight weeks,” Verma wrote.

Medical experts say there’s no evidence that any vaccination, including the COVID-19 vaccination, influences your chances of getting pregnant.

So people seeking an abortion in Texas will probably have to see a doctor even sooner than they would for a routine examination of a wanted pregnancy.

Besides, what the legislation defines as “heartbeat” at six weeks of pregnancy is not a heart beating. A true heartbeat is the sound of cardiac valves opening and closing. At the stage where abortion is banned in Texas, the embryo is less than half an inch long — somewhere between the size of a pea and a raspberry. Those cardiac valves have not yet developed.

What ultrasound technicians are hearing is actually electric impulses, Verma said, which the machine can translate into what sounds like a heartbeat.

“Those electric impulses do not make the sound of a heartbeat on their own, nor do they suggest that the heart is now developed. This is not a particularly important part of fetal cardiac development, even though it may be an important moment for my patients who are connecting with their pregnancies,” Dr. Verma wrote. A real heartbeat, she added, can’t be detected by ultrasound until 17 to 20 weeks into a pregnancy.